The Technics of a Master of Arts

Renaissance artists turned the canvas into a mirror of reality. To properly portray it they had to overcome the statics of their medium. Leonardo da Vinci relied on mystery, and his worldview naturally filled his paintings with motion.

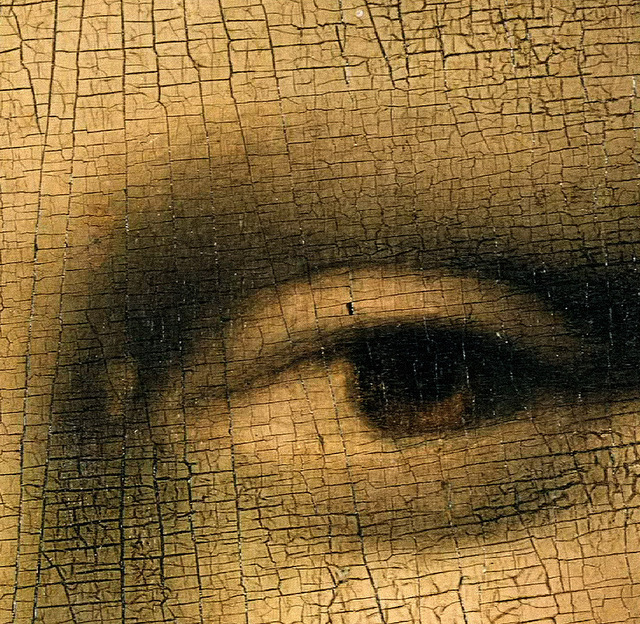

Image: Mona Lisa's Eyes (fragment), Leonardo Da Vinci, 1503—1505

Renaissance artists turned the canvas into a mirror of reality. To properly portray it they had to overcome the statics of their medium. Leonardo da Vinci relied on mystery, and his worldview naturally filled his paintings with motion.

Anyone who looks intently at the hollow of the Mona Lisa’s throat will see her pulse beating, wrote renown Renaissance art historian Giorgio Vasari in The Lives of the Artists. In 1950 art historian E.H Gombrich added: “its as if she were watching us and thinking for herself. Like a living human being she seems to change before our eyes, and gaze at us differently every time we turn to her.” “The image seems to ‘breath,’” concluded Leonardo scholar Martin Kemp in 2004.

Mona Lisa's Eyes (fragment), Leonardo Da Vinci, 1503—1505

Mona Lisa's Eyes (fragment), Leonardo Da Vinci, 1503—1505

How was Leonardo da Vinci able to create a portrait so perfect, five hundred years after its making men and women are still amazed by the liveliness of its sitter?

During the Renaissance artists outgrew the flatness of Gothic and Byzantine art. By inventing a set of mathematical and geometrical rules they were able to turn a two-dimensional canvas into a ‘window to the world.’ Da Vinci learned the laws of perspective apprenticing at the studio of the famous Florentine artist Andre del Verrocchio. Like the great painters of his time he could recreate the illusion of infinite space.

But Leonardo’s understanding of nature as a series of interlinked phenomena in a space continuum made him approach perspective differently. His study for the Adoration of the Magi (1481) looks like a flipbook. He drew the same figure in faintly different sizes and slightly different places to see how it best interacted with the others. It is as if he were creating a musical scale and looking for the notes making up a melody.

Mona Lisa (fragment), Leonardo Da Vinci, 1503—1505

Mona Lisa (fragment), Leonardo Da Vinci, 1503—1505

His guide was nature, and he’d rather follow its design than stick to the laws of mathematical harmony artists invented to reproduce the epoch’s conception of beauty.

The movement of his drawings and the heightened tension he achieved between the figures in his paintings, give movement to his works. “He brainstormed on paper,” writes Kemp in his book Leonardo. “Scribbled furiously, overlaying alternatives in dense tangles and dashing from one part of the sheet to another.”

The rules of perspective determined a figure’s size depending on its position in the painting. To create the illusion of distance, artists proportionately reduced the size of objects in the canvas. But Leonardo’s careful study of nature taught him the effect other phenomena have on how things seem to us from afar. Thus he blurred his figures’ contours and added a bluish shade to them to mimic the way light and air affect our sight.

The blurring technic has an additional impact on the observer’s gaze, and Leonardo fully embraced it. Blur lines leave spectators guessing, adding mystery and motion to a painting.

Da Vinci, Study for the background of the adoration of the magi, Uffizi.jpeg

The method invented by Leonardo is called sfumatto. He applied it on the Mona Lisa, particularly on the edges of her eyes and lips, a face’s most expressive features. As a result spectators are never sure whether she’s truly smiling or if it’s a glimpse of sadness they recognize in her eyes.

He added motion to the portrait by painting its background uneven. The right side is slightly higher than the left. When the spectator focuses on the painting’s right-half, Lady Lisa seems a bit taller or as if she were sitting more upright.

For five hundred years scholars have been feeding the Mona Lisa’s mystery by speculating whether the woman in the painting is in fact Lady Lisa Gherardini, whether it’s another woman, or if it’s a self-portrait in disguise.

Yet the real magic of the Mona Lisa doesn’t lie in its optical tricks, but in the fact that her mystery remains intact even though we are aware of them.