‘The Renaissance Nude’ in the Royal Academy of Arts, London

London’s Royal Academy of Arts has just opened a splendid new exhibition on ‘The Renaissance Nude’, charting depictions of the naked body in Europe from 1400-1530 in a range of different media media, from painting to sculpture, from engravings to illuminated manuscripts. Highlights include Titian’s Venus Anadyomene, from the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, and Bronzino’s St Sebastian, from the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

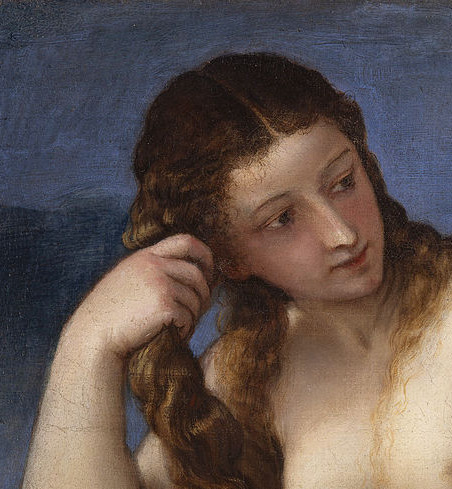

Image: Titian’s Venus Anadyomene, from the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, c.1520, the fragment

London’s Royal Academy of Arts has just opened a splendid new exhibition on ‘The Renaissance Nude’, charting depictions of the naked body in Europe from 1400-1530 in a range of different media media, from painting to sculpture, from engravings to illuminated manuscripts. Highlights include Titian’s Venus Anadyomene, from the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, and Bronzino’s St Sebastian, from the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. There are also works by Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael, Lucas Cranach, Dürer, and Pollaiuolo. The exhibition, in the Sackler Wing of Galleries, runs until 2nd June 2019.

Titian’s Venus Anadyomene, from the National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, c.1520

Since the Renaissance, the depiction of the naked human body has been a defining element in European art. Rarely, however, has a whole exhibition been devoted to this topic. The ‘Renaissance Nude’, curated jointly by Thomas Kren of the Getty Museum and the Royal Academy’s Per Rumberg, aims to fill that gap by examining depictions of the naked body at the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Renaissance (1400-1530).

As this exhibition shows, Renaissance artists’ interest in depicting naked bodies was closely connected to the intellectual currents then coursing through Europe: from the rediscovery of classical literature and sculpture and the spread of secular humanism to the development of the printing press and challenges to the authority of the Catholic Church.

The exhibition is arranged thematically over five galleries, each containing works in a variety of media (paintings, engravings, sculpture, bronzes, books), and from different regions (primarily Italy, Germany and the Low Countries). This synoptic approach allows visitors to gain an ideaof the variety of traditions and artistic practices on display.

The dominant image of Gallery 1 (‘The Nude and Christian Art’) is a series of depictions of St Sebastian, who was martyred by being stripped naked, tied to a tree and shot with arrows, before he was miraculously rescued. Visitors can contrast a silver reliquary (1497) which, in line with its devotional function within the medieval Christian tradition, focuses on the saint’s suffering, with a painting by Cima da Conegliano (1500-02), which, in the spirit of the Renaissance, is dominated by the saint’s idealised, golden-hued body standing before a turreted Italian town, with only a single arrow in his slender thigh to allude to his martyrdom.

St.Sebastian, Cima da Conegliano (1500-02)

The culmination of the St Sebastian images is Bronzino’s Mannerist version (c. 1533) in Gallery 5. This Sebastian’s torso is encircled in a scarlet cloak, echoing the auburn of his curly hair, and complementing his large, grey-green eyes. A bloodless arrow sticks casually out of his side, almost as an afterthought; in his hands he toys, like Cupid, with another. The distinctive features of the sitter have led to speculations that he was Bronzino’s young lover. Instead of using nudity to reinforce a religious message, the artist has used the religious theme as an excuse for a portrait.

Gallery 4, ‘Beyond the Ideal Nude’, continues the Christian theme of the mortification of the naked flesh. One grisly example is The Torture of Saint Barbara by Knife and Scourge(attributed to Konrad von Vechter, c. 1430-35): St Barbara, a beautiful young woman, stands stripped to the waist as a soldier begins to slice off one of her breasts. Another is a rare polychrome wood statue of St Jerome from the 1460s by Donatello, which shows the early church father, with bulging veins and emaciated limbs, in the act of scourging himself with a rock. The lesson which these works teach is that the naked body, far from being worshipped, is there to be abused in the interests of spiritual enlightenment.

This Christian treatment of nudity contrasts strikingly with the secular, classicising approaches displayed in Galleries 2 and 3.

Gallery 2 (‘Humanism and the Expansion of Secular Themes’) focuses on thThis was the name given to a painting presented by the fourth-century Greek e influence of classical mythology and literature on Renaissance nudes. The highlight is Titian’sVenus Anadyomene (‘Venus rising from the sea’, c. 1520). artist Apelles to Alexander the Great. Titian’s work can be seen as a challenge to Apelles’ legendary supremacy. While other Renaissance artists, notably Botticelli, also painted the same subject, Titian’s stands out for the simplicity of its composition. His goddess is depicted as standing in the sea up to her thighs, the shell from which she was born relegated to a token in the background; the sky behind her is stormy and overcast. The sensuous contours of her naked body seem to crowd the frame, her head towering among the clouds, far above the distant horizon. Perhaps influenced by a description in the Roman poet Ovid, or by the pose of Hellenistic statues, she is pictured in the act of wringing out her long hair. Even after five hundred years, the colours retain their spellbinding hue.

The eroticism of Titian’s Venuscontrasts with male nudes of the period such as Pollaiuolo’s bronze of Hercules and Antaeus wrestling (1470s). This responds to the challenge of representing male bodies in strenuous motion accurately and from all angles. Particularly striking is the success with which the sculptor has differentiated the faces of the two wrestlers. While Hercules has a tranquil, Apolline profile, Antaeus’ features are thicker set and show the strain of being lifted bodily off the ground (the only way that he could be defeated).

Gallery 3, ‘Artistic Theory and Practice’, explores the way in which Renaissance artists studied classical sculptures, such as the Apollo Belvedere (excavated c. 1489), as a way of improving their understanding of the human form in different postures.

Apollo Belvedere, Vatican Museum

The influence of sculpture on other artistic media is illustrated by Andrea Mantegna’s Battle of the Sea Gods (before 1481). Inspired by ancient friezes, this bizarre, dreamlike engraving depicts what look like animated Greek sculptures, not only in their physique but even in their smooth noses and blank expressions, engaged in a slow-motion fight on the edge of a reedy bank.

Two fine anatomical sketches (c. 1510-1511), depicting the sinews of a shaven-headed man’s shoulder and neck, demonstrate Leonardo da Vinci’s scientific curiosity about the operation of the body. This distinguished him from contemporaries like Raphael and Michelangelo, whose sketches of the naked body focus on its external appearance rather than inner workings. To complement the drawings, books by Cesare Cesariano and Francesco di Giorgio demonstrate the theoretical interest that was taken in Vitruvius’ analogy between the human body and an ideally proportioned building.

As works like the Venus Anadyomene and the Battle of the Seagods demonstrate, one of the challenges of Renaissance art is that it often requires significant background knowledge in order to appreciate it fully. While it is always difficult to decide how much of that information to communicate to the visitor, the overall impression of this exhibition was that more detail could have been provided in the printed notes.

The need for more information is particularly acute in Gallery 5, ‘Personalising the Nude’, which examines the role of Renaissance patrons in the commissioning of nudes. The gallery contains four works commissioned by Isabella d’Este, one of the period’s rare female patrons, including Perugino’s Combat Between Love and Chastity (1503-5). While we are told that d’Este ‘provided minute instructions’ for this busy allegorical scene, in which goddesses, Cupids and other figures in various states of undress wage a stylised battle, it is a shame that we are not told why she commissioned this painting in the first place.

Perugino’s Combat Between Love and Chastity (1503-5)

Finally, one theme conspicuous by its absence from the exhibition is ‘the nude and the erotic’. There are numerous sexually charged works on display – from Dürer’s homoerotic woodcut, The Bathhouse (c. 1496), to Pisanello’s Luxuria, which some have speculated may, uncomfortably to the modern viewer, represent an African slave woman as a personficiation of bestial ‘Lust’. Perhaps, though, drawing attention to the sometimes disturbing eroticism of the artworks would have courted the wrong sort of publicity. Instead, viewers are once again left to discover the connections for themselves.

In short: this is a fascinating exhibition – but not for the fainthearted.