The Art of Ideas: An Interview with Mel Bochner

A leading figure in the development of Conceptual Art, since the 1960’s Mel Bochner has pioneered the presence of ideas, language and philosophy in the visual landscape. From artistic convention to unspoken and coded ideologies, Bochner has questioned the relationships between art, color, words and space to realize how they profoundly affect our worldviews.

A leading figure in the development of Conceptual Art, since the 1960’s Mel Bochner has pioneered the presence of ideas, language and philosophy in the visual landscape. From artistic convention to unspoken and coded ideologies, Bochner has questioned the relationships between art, color, words and space to realize how they profoundly affect our worldviews. He is further credited with contributing inventive vehicles of expression to the art cannon, including use of gallery walls as the subject of a composition and use of photo documentation for ephemeral and performance pieces. Through his evocative installations and process-oriented pieces, Bochner incorporates photography, found objects, ephemera and performance to discover the notion of what an art work is or should be. Rather focusing on direct interpretation, he is always more interested to see what responses his works elicit. ArtDependence spoke with Bochner to learn more about the motivation behind his art, his journey as an artist and what is next on the horizon for him.

ArtDependence: Much of your work is informed by your attempt to reconcile two divergent art perspectives: the theoretical/formal and the open-ended/intuitive. How do your concepts and practice merge the schools of thought?

Mel Bochner: It’s always in the back of my mind. I don’t think it’s an exploration so much as a realization that those contradictions are always there, and there is a level of ambiguity that you have to be willing to tolerate.

AD: How has your study and interest in philosophy inspired your work throughout the course of your career?

MB: In my earlier work, I really wanted to look at the world as I found it. Then at a certain point, I became less interested in that kind of objectivity and more interested in my own responses to the world – my own subjectivity.

AD: Your art emphasizes both color and language. Which aspect is most important to you as an artist, the codes and ideologies of language or the visual and emotional experience of color?

MB: I think it is a pendulum, it swings back and forth. Language is the world we share with others. Color is one’s own response to it. There is no shared view of color, it’s always subjective.

AD: How do you conceive of the role of the viewer in creating meaning for a piece and the aesthetic experience of a work?

MB: The Duchampian answer is that the audience plays a major role in terms of its eventual meaning. But for me, the audience does not play any role in the making of the work. My first audience is myself. And since I do not consider myself that different from anyone else, I assume that my responses are not that different from anyone else’s…Of course, then when you read what the critics say, you find out that your responses are very different from everyone else [laughs].

Breach, 1983. Oil on sized canvas. 103 X 89.5 inches. Courtesy the artist and Peter Freeman, Inc.

Surge, 1983. Oil on sized canvas. 110.5 X 92 inches. Courtesy the artist and Peter Freeman, Inc.

AD: You have said: "What I’m trying to do is make the painting physical enough and complex enough that I lose intellectual control. Getting inside the painting isn’t the problem, it’s how to get out of it." Expound upon your ideas and this process.

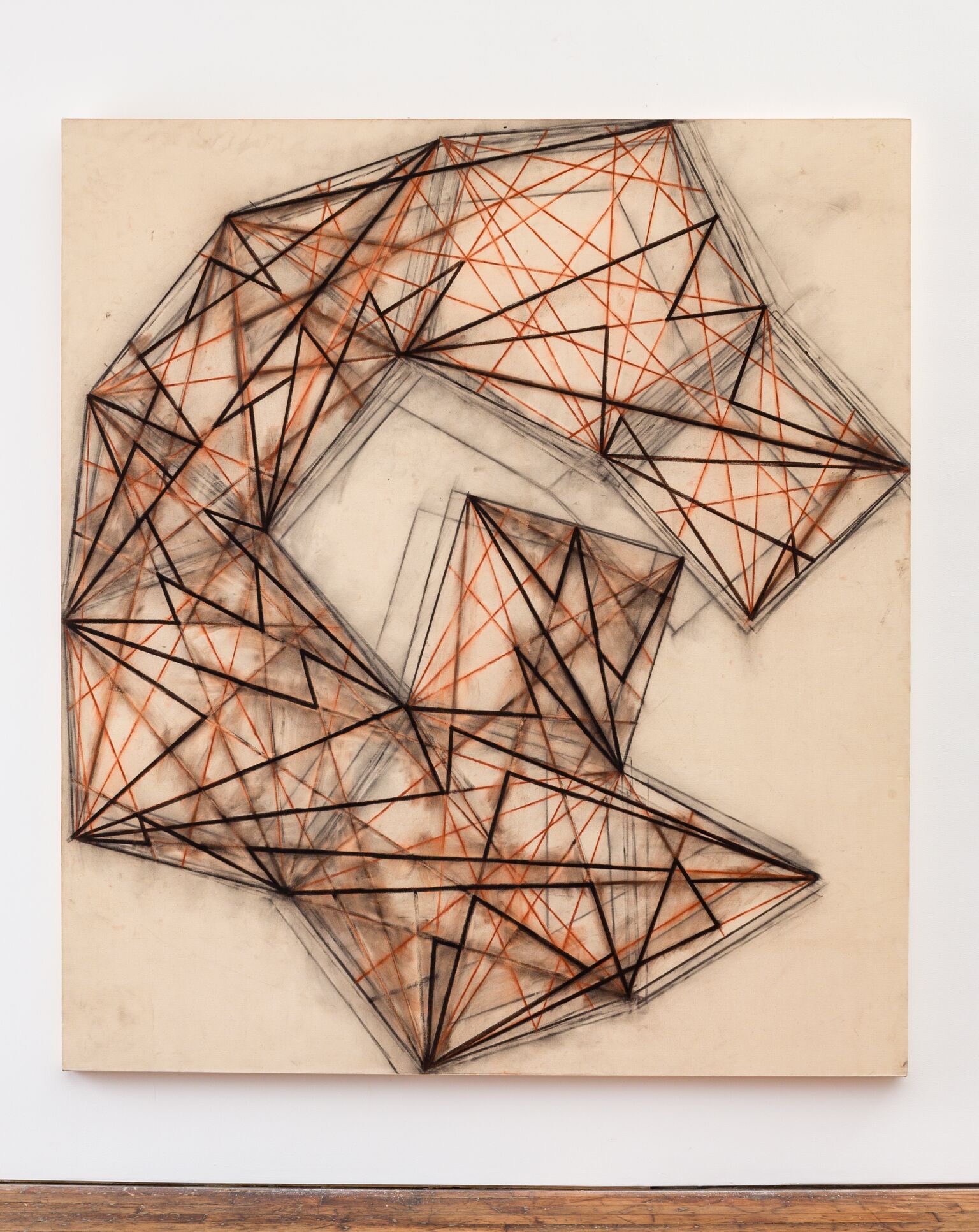

MB: I still agree with that. In my earlier work before 1981, I was very conscious of setting up a space between myself and the work. I used various devices and ideas to do that, for example photography. A photograph that you see hanging on the wall is not something that you made personally. As my work evolved, I wanted to be more inside the work, so that is very much what these paintings were about, how to lose myself inside the act of painting but not to make it into any kind of conventional, expressive painting. The problem of getting out of the painting is the problem of knowing when it’s finished.

AD: How do you know when you have reached an end point?

MB: When your mind stops working, when you cannot think of what to do next, then you’re probably finished.

Then there’s the old axiom we learned in art school: underdone beats overdone.

AD: At the current ADAA show, you are exhibiting pieces from the 1980's, when your work was focused on geometric concepts and spontaneity. How have the prominent shapes anchoring much of this work, the triangle, square, and pentagon, affected manifestations of your work in that era and since?

MB: I started using those primary three-sided, four-sided and five-sided shapes in the early 1970’s. They became, in various combinations, the basis for most of my work for the next ten or fifteen years. Something that artists have been searching for, since the beginning of modernism, has been shapes that are neither geometric nor organic. Of course, all shapes fall into one or the other category but in combination the triangle, square and pentagon yield shapes that are both geometric and organic. That intersection between geometry and biology fascinated me for a long time.

AD: How does the work from your 1980's period tie in with your recent work and return to the spontaneous aspects of painting and language?

MB: My interest in language was revived when I discovered a new edition of the thesaurus and I found that, in the intervening forty years, what was considered ordinary language had really changed. Now you had all kinds of slang and vernacular, up to and including obscenity in a book that kids in grade school use. That seemed to me to be a really interesting place to explore the collision of language and politics.

AD: There is much more variance to what now defines language than there once was. Do you think that is for better or for worse?

MB: Probably neither, I don’t attribute any value to it. I think it reflects contemporary discourse, where we are right now. Just turn on TV at night and there it is. In other words, I think it’s a tidal wave that you can’t hold back.

AD: What do you feel is the role of art socially?

MB: It is to move people, and make them think.

Ultima Thule, 1983. Oil on sized canvas. 99 X 115 inches. Courtesy the artist and Peter Freeman, Inc.

AD: You have said: “Looking at a painting is an act of mentally reconstructing its history. I don’t want to camouflage the arguments that took place, the doubts, or the conflict." In what ways do the negative elements add to the viewer's experience of the work - do they depict a fuller truth?

MB: You could put it that way. For me, it simply keeps me in touch with the road I’ve taken to arrive at the painting, and where I might have taken a different route. In the words of Yogi Berra: “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.” I like keeping all the untaken forks open.

AD: What can audiences expect from your work in two upcoming exhibitions: Shape of Light: 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art at the Tate Modern in London and E.A.T.: Experiments in Art and Technology at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul, Korea?

MB: The show at the Tate is about the relationship of photography to sculpture. I think that my early photography beginning in 1966 was very much in response to issues in sculpture. I wanted to make sculptures that had zero mass. The E.A.T. exhibition is an omnibus history of E.A.T. projects, which I am sure you know was organized by Robert Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver. I did some projects with them. I was an artist in residence at the Singer Laboratory in New Jersey. I would go there two or three days a week and have conversations with their mathematicians, scientists and engineers. All of my thinking about measurement came from those conversations.

AD: What are you working on presently?

MB: I don’t really work in terms of a “project” or anything that’s goal-oriented. It’s more like “one thing leads to another.”

AD: You have said that it is very important for you to follow your art wherever it takes you, in spite of the ends. How integral is your process to the art you create?

MB: I am not interested in repeating myself. When I go into the studio in the morning, I hope to have something I wasn’t expecting when I leave in the evening. It doesn’t always happen, but when it does, it’s the feeling that you live for as an artist.

AD: When you look back over your career of more than five decades, what was your favorite period or moment?

MB: Today.

Image on top: Number One, 1981. Charcoal and conte on sized canvas. 90 X 80 inches