The Aestheticized Interview with Timo Menke (Sweden)

Timo Menke is an interdisciplinary artist living and working in Stockholm. Investigating the relationship between the observer and the observed, subject and object, recorder and projector, lens and screen, his practice is increasingly aiming at a dark holistic approach. Using photographic and moving images, documents, objects, drawing and plant cultivation he approaches, renegotiates and speculates about our common nature-culture, in order to highlight and transform an increasingly dark matter: body, earth, space.

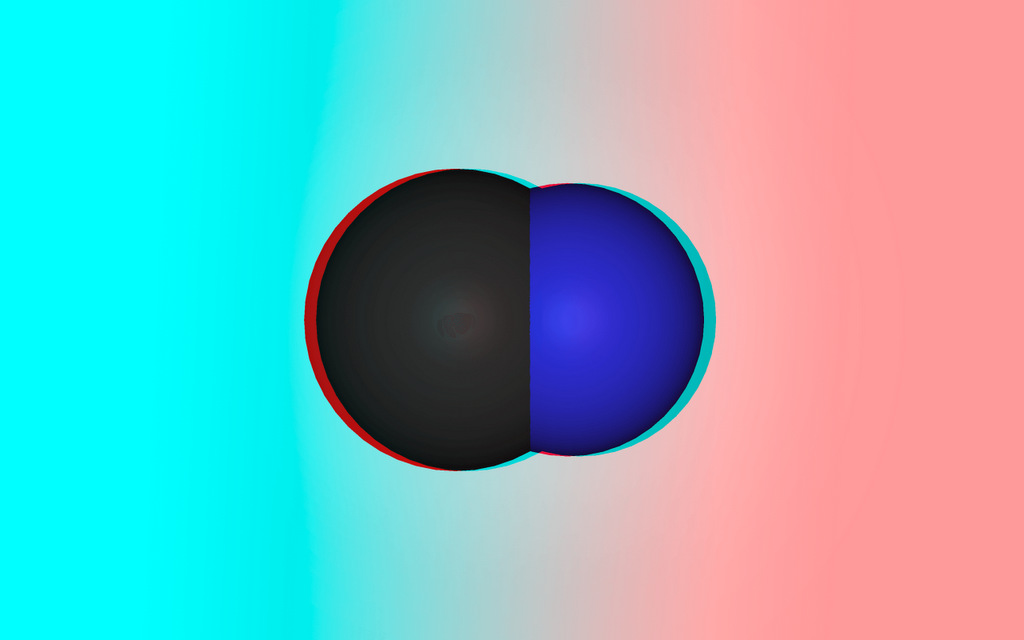

Image: O≡Cyan (Project in progress), Sketch for lenticular/anaglyph 3D-image with cyanide-ion.

He graduated from Konstfack in 1999 where he was also an Assistant Professor in the Art Department between 2004-2014. Menke is represented by Moderna Museet Stockholm (Modern Art Museum in Stockholm), Kalmar konstmuseum (Kalmar Art Museum), Pori Art Museum and is distributed by Filmform – The Art Film and Video Archive.

Upcoming and recent exhibitions include Alma Löv Museum of Unexp. Art, Östra Ämtervik (2020), Köttinspektionen, Uppsala (2019), Långban Gruv- och kulturby, Filipstad (2019), Nacka konsthall, Stockholm (2019), ID:I Galleri, Stockholm (2018/2019), Ahlbergshallen, Östersund (2018), Galleri 54, Göteborg (2018), Gallery Molekyl, Malmö (2018), Spanien 19c, Aarhus, Denmark (2018), Pori Art Museum, Pori, Finland (2018), Kalmar Konstmuseum & Galleri Verkligheten, Umeå (2015), Moskvabiennalen (Special Project 2015 & 2013), Manifesta St Petersburg (Special Project 2014), Konsthall C, Stockholm (2008).

ArtDependence (AD): Do you have any thoughts on whether that’s a responsibility of artists, reflecting our time is important within the political context?

Timo Menke (TM): As the planet is facing the global COVID-19 outbreak and a pandemic state of mind, yet to last for weeks or months, “that” might not be the responsibility of artists. However, the ongoing quarantine is affecting the art world, and its underlying structures and problems, in ways that inevitably will lead to change – wanted or not. And that change is also in the hands of every artist, whether it’s about biased hierarchies, unequal support structures, false belief systems, or the very art produced. The heightened awareness concerning climate change and new activist modes of artmaking right before the pandemic was a head start, but COVID-19 creates a sense of acute fragility and vulnerability among us, not only medically, but economically and last not least aesthetically. In retrospect, i.e when (or if?) the pandemic is history, maybe we will be able to see pre- and post-pandemic art, artists, galleries, collectors and audiences? To put it simple: the world you choose to support now, is the world that will exist after.

Gifted Men, Duo Show Lahjoittajien Muotokuvia – Donor Portraits with Nils Agdler at Pori Art Museum, Pori, Finland, 2018. © Nils Agdler

AD: What is your main interest as an artist? What form of self-consciousness is applicable to art-making?

TM: I usually describe myself as an interdisciplinary artist. Investigating the relationships between the observer and the observed, subject and object, recorder and projector, lens and screen, my practice is increasingly aiming at a dark holistic approach. Throughout all of my projects, photographic and moving images, documents, objects, drawing and plant cultivation are utilized to approach and speculate with and about an increasingly dark matter: body, earth, space. This rather distilled worldview can sound a bit academic, although I try to be as hands or eyes on as possible. I’m operating in a spectrum of integrated visual, material and linguistic approaches and any human perspective is there to connect to and become with more- and less-than-human agencies, lifeforms and possible “horizontal transfers” (terminology borrowed from genetics). I can’t stop referring to Rosi Braidotti’s term “becoming with”, a process or situation of “bothness” in relation to any “other”. Where do I end and they begin? This informs a connected ethical codex I try to balance: do my projects operate on behalf of or at the expense of the subjects involved?

AD: Do you feel that it’s important to convey your own beliefs and opinions within your art? Is there a philosophical element in your work?

TM: Re-reading the statement from question 2, I have to admit there is a larger bulk of philosophical underpinning that drives my practice. But there is always a sense of ambivalence and ambiguity in relation to that. If you need a PhD to get the idea, I think I failed. Sense and sensibility come first, especially since I often deal with paradoxical or complex phenomena I don’t even know where to place myself in relation to. I guess, that kind of hypersensibility to one's own work and its semantic simplification can get in the way: any clear message can blur and obscure the perfect nonsense hidden inside.

Cogito Ergo Pisum, Group show Där Världen Kallas Sog with Timo Menke, Hanna Ljungh, Lina Persson, Niklas Wallenborg at Köttinsspektionen, Uppsala, 2019. © Jean-Baptiste Béranger

AD: What are you currently working on? Is there anything in particular that you’d like to get across through your work?

TM: At the moment I’m struggling with how to start up a project that has very diverse outsets and methodologies at its very beginning. “O≡Cyan” deals with a dark material-semiotic inquiry into cyan and cyanides. Cyan with its typical green-blue color shades, connected substances, organisms and techniques are the central starting point. Cyan emerges in photochemical and photosynthetic processes surrounding and imaging us: in the CMYK colour space, cyanide poison, cyanobacteria and cyanotypes, simultaneously natural and unnatural, toxic and vital, additive and subtractive. Nazi cyanide capsules, cyanobacterial algal bloom and cyanide leaching in gold mining mark their outermost horizon. “O≡Cyan” might cover a range of tools from photographic to cinematographic recordings, from bluescreen to greenscreen, from cyanobacterial to cyanotype realisations, slowly building up a dark material essay. This project description is kind of typical for the holism I am going after, in attacking my subject matter from different perspectives and angles, last not least from within the subject matter. The possible polyphony of utterances demands multiple personae dealing with each part of the puzzle. It’s multi rather than mono. Apart from the artistic challenges, there is a whole logistics of having everything in place: from the studio space, to advanced lab access, to financial support. The good thing is, I’m in no rush, but embrace the long-term almost “eternal” work process by which things can emerge and unfold over many project cycles, similar to my work with “Cogito ergo Pisum”.

AD: What place does creativity have in education? Do you view yourself as a creator?

TM: “Creator” with its god-like implications is a contested term to my ears. After more or less 15 years of teaching art and filmmaking at Konstfack (University of Arts, Crafts and Design, Stockholm) the educational perspective always pops up. I’m not sure where to push the answer to this question though.

O≡Cyan (Project in progress), Sketch for lenticular/anaglyph 3D-image with cyanide-ion.

Obviously, creativity should have a much larger place and acknowledgement in both society in general, and in education specifically, not only in Arts education. However, creativity can be a bit of "One size fits all", inoffensive to its practitioners and educators, and confirming conventional understandings of arts and crafts. Along with creativity, there is a growing need for visual literacy, toolkits to analyze and question the profoundly visually saturated culture we’re living in. Anyway, I don’t think we can do without the critical, the challenging, the speculative, the nasty stuff that can bring radical change.

AD: Do you think that by challenging conventional views, art can truly make a change in the public’s perception?

TM: Seems I had that covered in the last answer.

AD: How has your work developed since you began and how do you see it evolving in the future?

TM: One way to put it, is to say: from a documentary into a much more speculative approach. Moving images have long been my primary method, motif and motor, and in earlier works you can spot a historiographical urge, which coincided with the nineties realist turn. My long-term collaborative projects with Nils Agdler include film works and installations on electrical hypersensitivity (Fugitives from the Fields, 2005), and commercial anonymous sperm donation (Made in Denmark, 2013 and Gifted Men, 2015). After “Gifted Men” I became extremely exhausted with film as both medium and method, and the focus on sperm as biomatter had already sparked a completely different interest in DNA as artistic media and matter. Ever since I have cultivated a growing flora of techniques and tools appropriate for dealing with post-human and multispecies questions. In “Cogito ergo Pisum” (2018-ongoing) I have been interested in human-plant symbioses, on both symbolic and biosynthetic premises. Once I had completely evaded film and camera, I could rediscover it on a totally inverted level, e.g. by returning to 1800th century methods like cyanotypes, cameraless negative photograms. Whether rediscovering or completely inventing new methods, the dark holistic approach I am to put to work seems here to stay.

Gifted Men, Duo Show Lahjoittajien Muotokuvia – Donor Portraits with Nils Agdler at Pori Art Museum, Pori, Finland, 2018. © Nils Agdler

AD: Is sophistication, aesthetic accomplishment in the eye of the beholder?

TM: I think it’s in the eye of the context, of which the beholder can be part of. This points towards an individually acquired taste, a result of education and socially stratified access to art in general, but also the kind of ghost audience we might have in mind: who and where is the viewer that can comprehend and appreciate this? I think that the viewer, or the beholder, is always somehow embedded and situated in the context that produces possible sophistication. That is as much an argument against aesthetic autonomy, as against “anything goes”.

AD: What do you think is the social role of art? How would you like to be remembered?

TM: That is two questions forced together. The social role of art has become more apparent and more important, especially in these socially distanced pandemic times. For my own part I am not and never was very interested in the type of solitary confinement studio approach – people locked in to their own practice for months, to surface only for their own high-brow art shows. I think there are more than ever strong forces around the globe opening up artistic practice at its core, fostering exchange, collaboration and knowledge producing, and I strongly believe that this points to a future where art making less and less is about collectable artifacts, but rather collective efforts for change.

I recently asked a close acquaintant for a reference letter, which forced me to break down my bio into a comprehensive text. I was happily surprised to read a sentence like “he has developed an impressive ability to quickly adopt new knowledge and skills in his artistic career, while also challenging his modes of production, and aiming for a critical understanding of subject matter and related methodologies.” It’s the multi over the mono for me.

AD: How does art school form ideas about art? Does it shape people into being certain types of artists?

TM: Quite frankly: probably. As an institution it’s inevitable to form ideas, opinions and even certain tastes of art among students during education. And by no means is it the work of a teacher or faculty only. I have seen strong cases, where students had much deeper influence on each other, pushing their skills and tastes. My point is that school is not merely a place, and a teacher is not merely a position, but education as a process can build strong relations - to ideas, things, to people, and last not least to yourself. That said, education can take place anywhere, anyhow and with anyone, but art schools in particular can offer a space for that to happen. With all due respect for the art world system of education and the much professionalized structures many academies have applied in the last decade or so, and thus “producing” star artists the way your question implies, I want to stand up for critical deschooling and unlearning within formal education. Whatever that means in specific contexts and territories, we need to constantly rethink how education is scripted by “pros”, rather than in the hands of those who seek training. In the end we all need to take responsibility for our own learning.

Cogito Ergo Pisum, Group show Där Världen Kallas Sog with Timo Menke, Hanna Ljungh, Lina Persson, Niklas Wallenborg at Köttinsspektionen, Uppsala, 2019. © Jean-Baptiste Béranger

AD: What do you think about the art world and art market? Do you accept that art is inherently an elitist activity?

TM: Honestly, it took me a while to fully understand and see through the smoke screen, the very special way in which art is embedded in and promoted by e.g. art fairs as an investment, and how the capitalist driven art market confirms itself aesthetically and socio-economically in a kind of feedback loop. That is true not only for the face value produced, but also for the seemingly colorful monoculture and monopoly this leads to: once famous and hallmarked, it’s the same dude everywhere for a long time, no names mentioned. There is nothing for me to accept, but I have to live with it – or without it. Maybe “the pandemic is a portal”, to speak with Arundhati Roy, as the nepotism and favoritism become ever more obvious and dubious, now that the crisis hits everyone equally hard. But that remains to be seen.

AD: What’s the last great book you read? Any other thoughts/projects to share?

TM: The most mind blowing book by far for me was “Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence” (2016) by Timothy Morton, which left a huge mental footprint. At the moment I’m discovering Octavia Butler’s “Lilith's Brood” (1987–1989), a Sci-Fi trilogy that became synonymous with the term xenogenesis, still highly relevant in our xenophobic times. On my night table is also “The Last Man” by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, a literally heavy post-apocalyptic novel from 1826, so timely dealing with a pandemic outbreak that leaves only the main character alive. Dark readings in dark times!