Malevich as a Professor of the Kiev Bauhaus

We all know Kazimir Malevich as an artist, art theorist and philosopher. But we don’t know so much about him as a teacher or even professor. Yet, surprisingly, this was his main activity for at least 12 years. In the numerous research articles and papers on Malevich, you’re unlikely to find one on his pedagogical oeuvre.

We all know Kazimir Malevich as an artist, art theorist and philosopher. But we don’t know so much about him as a teacher or even professor. Yet, surprisingly, this was his main activity for at least 12 years. In the numerous research articles and papers on Malevich, you’re unlikely to find one on his pedagogical oeuvre. This may be partly because some of the archives and documents on this topic have only recently been discovered. A few years ago, the notebooks of his student in Vitebsk were found, giving the details of the education process at the beginning of Malevich’s teaching career. In late 2015 in Kiev, a huge archive relating to the work Malevich did whilst at the Kiev Art Institute was unexpectedly found. Documents and articles from this archive shed light on his late pedagogical views and practice, finally allowing us to piece all of this together.

After Malevich created Suprematism – a new art movement based on simple geometric forms – he quit art practice, saying a “brush can not get what you can with a pen. It is disheveled and can not reach in the convolutions of the brain, the pen is sharper”. He wanted to reach the depth of the artists’ brains and change lives through the means of art. He knew what to teach and how to do it. He only needed to know who to teach.

In 1919, at the age of 40, Malevich began teaching in Moscow at the state art and technical school, VHUTEMAS. But it was a short period, which proved to be just a rehearsal. Later that year he moved to Vitebsk (now Belarus) and headed a workshop in the Vitebsk Art School. It had just been opened by Mark Chagall as a new type of art school in a newly created Soviet State.

Very soon, Malevich’s charisma and new ideas found him surrounded him by a circle of devoted students with a self-ascribed name; UNOVIS (Utverditeli NOVogo Iskusstva – the Champions of the New Art). The group included Lazar Lissitsky, Nikolai Suetin, Lazar Khidikel, Illya Chashnik and others. They picked Malevich’s Black Square as an emblem and used it as their signature. They put a black square on the sleeve of their jacket and used it as a flag. They discussed the artworks of students and teachers, organised philosophical discussions, printed articles and designed the streets of the city for holidays. Shortly there were UNOVIS branches in different cities around the USSR – Moscow, Perm, Saratov and Smolensk.

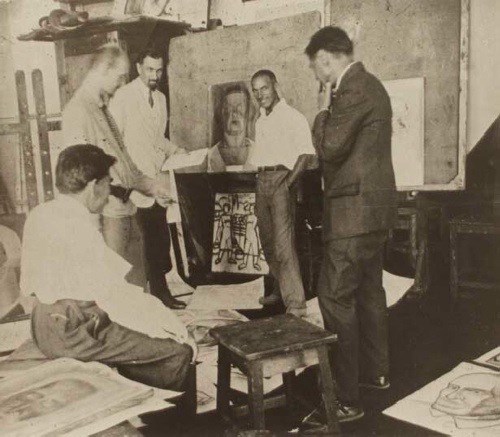

Kyiv Art Institute, 1930

Professors of KAI Lev Kramarenko, Mykhailo Boichuk, Oleksandr Bogomazov, director Ivan Vrona in the studio, 1927

In 1922 Malevich moved to Petrograd and most of the UNOVIS group went with him. The next year they led theoretical and pedagogical work in the Museum of artistic culture that later became GINHUK (State Institute of Artistic Culture). Over the next few years, Malevich created his theory of the “added element”, which became the core of his art theory and pedagogy. According to Malevich, each art movement has its special element, which is added to the form of nature and also has special colors that are more relevant to that particular movement. In cubism it was the “sickle-shaped curve” and in Suprematism the added element is “straight”. This theory allowed Malevich to build his own art history, paying most attention to the “isms” of the early 20th century. Malevich charted the results of his research on a dozen charts and took them to Berlin in 1927. These charts are now kept in various collections including MoMA and several European museums. They have also been recently exhibited.

Meanwhile, Malevich created a separate method for the art education process itself. It is usually referred to as a Medical method. He considered that each artist is sick with one of the “isms”, meaning he has a natural relevance to one of the art movements. In such case the Art School/Institute/Academy is a hospital and the art professor is a doctor. His main duty is to diagnose the illness and give a proper cure. Malevich considered that artists can’t all be taught in the same way. And you can’t make a Futurist out of a Cubist. So you have to give particular treatment to each student.

In the mid 1920’s, this form of art, which we now call avant-garde, failed to go along with the official doctrine. Shortly, the only permitted and allowed art became social realism. This meant no more exhibitions, publications, students or ways to work for Malevich. In 1927 he went abroad for a few months and visited Warsaw and Berlin. But his trip was terminated and he never had the chance to leave the Soviet state again. So he was left without work and hope in Leningrad with just a few devoted students and family.

Then, by chance, while in Kiev on family business, he met his colleague artists Lev Kramarenko and Andriy Taran. They were teaching at the Kiev Art Institute and suggested that Malevich could be invited to work there as well.

Maryan Kropyvnytsky

Students and professors of the Kyiv Art Institute, 1930’s

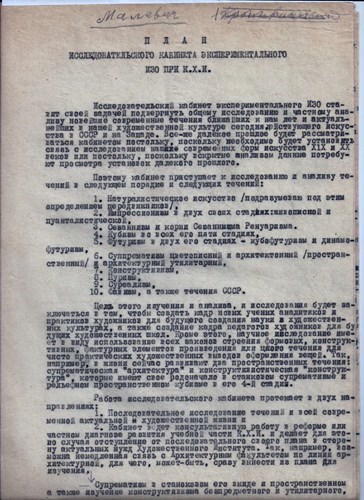

K. Malevich. Plan of the Experimental Office in Kyiv Art Institute, 1930. From M.Kropyvkytsky Archive

Since 1924, the Kiev Art Institute had been directed by a young and energetic cultural manager and revolutionary named Ivan Vrona. He wanted to create a Kiev Bauhaus in the Institute, which was based on the first Ukrainian Art Academy created in 1917. Vrona found a permanent building, added more departments and invited a number of artists and professors from around the USSR to bring new ideas and strategies for art education. In the mid 1920’s there was a great number of famous artists teaching in KAI – among them Vladimir Tatlin, Viktor Palmov, Oleksandr Bogomazov, Mykhailo Boichuk, brothers Krychevski, Lev Kramarenko and others. Malevich was a perfect candidate to join the team. He was from Ukrainian origin and spoke Ukrainian – which was obligatory during the politics of Ukrainization. It took some time to get the necessary permissions from Kharkiv – the then capital of Ukraine – and Malevich was invited to work as a professor in the Kiev Art Academy. He came to Kiev for 10-14 days per month and the rest of the time he spent in Leningrad working at the Art History Institute.

In April 1928 he started publishing a series of articles in Nova Generaciya magazine – the main tribune of the Ukrainian futurist artists. 12 articles were published in total from 1928 to 1930. Later, he put the articles together in a book with the name Izologia and negotiated to get it published in Kiev, but it never happened. This was supposed to be his last book.

Until late 2015, we had just a few facts about Malevich’s time in Kiev. The discovery of the Maryan Kropyvnytsky archive changed that. It was miraculous. There had been no signs of the archive since the 1930’s. Maryan Kropyvnytsky was an artist and had just graduated from the KAI himself, when director Vrona assigned him to be an assistant in the Research Office of Experimental IZO, opened by Malevich. Kropyvkytsky also kept all the minutes of the meetings of institute staff and Malevich and his articles. After a wave of political cleanup in the institute, when the most progressive professors along with director Vrona were fired, Kropyvnytsky also left the institute, keeping the archive at home. Many years later he was approached by researchers but refused to reveal anything about the archive. Only after his death, his daughter discovered numerous documents related to Malevich in her father’s volumetric archive. It was only in 2015 that the family decided to open the archive and allow it to be published. In 2016, the Kiev publishing house Rodovid released a volume of materials relating to Malevich’s time in Kiev between 1928-30. For the first time, the picture became clear on how deeply Malevich was involved in Kiev’s art situation.

Among the archive’s most valuable pieces, there was a Plan of the Research Office of Experimental IZO. It stated Malevich’s frame of work in Kiev and a number of articles, mostly devoted to local art and education issues.

It is hard to tell where he stayed in Kiev. Most probably it was a room in the Institute’s block. He often visited his friends Lev Kramarenko and Iryna Zhdanko. It was in their apartment that he created a sketch for the conference-hall of the Ukrainian Science Academy that is kept in the National Art Museum of Ukraine along with the letters from Malevich. There is a lonely peasant woman on a sketch with small little houses in the background. The drawing has an anxious and tragic mood. It looks more like a funeral at the cemetery than the wealthy village of Malevich’s childhood. For Kramarenko, Malevich’s position was obvious, thus he never showed this sketch to anyone.

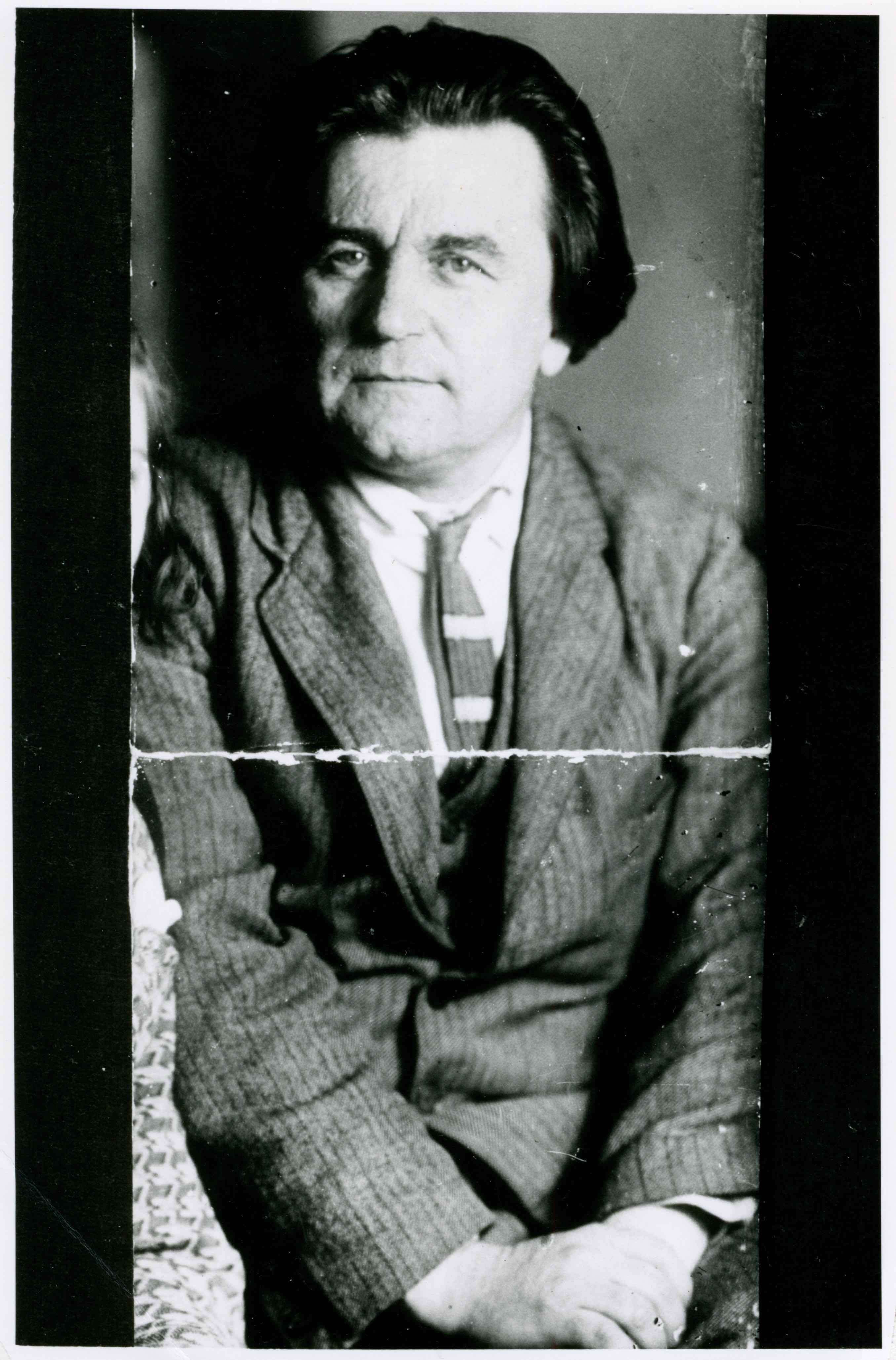

Image on top: Kazimir Malevich, 1927