Lost Artemisia Gentileschi Painting Rediscovered in the Royal Collection

A rare surviving painting by Artemisia Gentileschi, the greatest female artist of her generation, has been rediscovered in the Royal Collection after being misattributed at least two centuries ago.

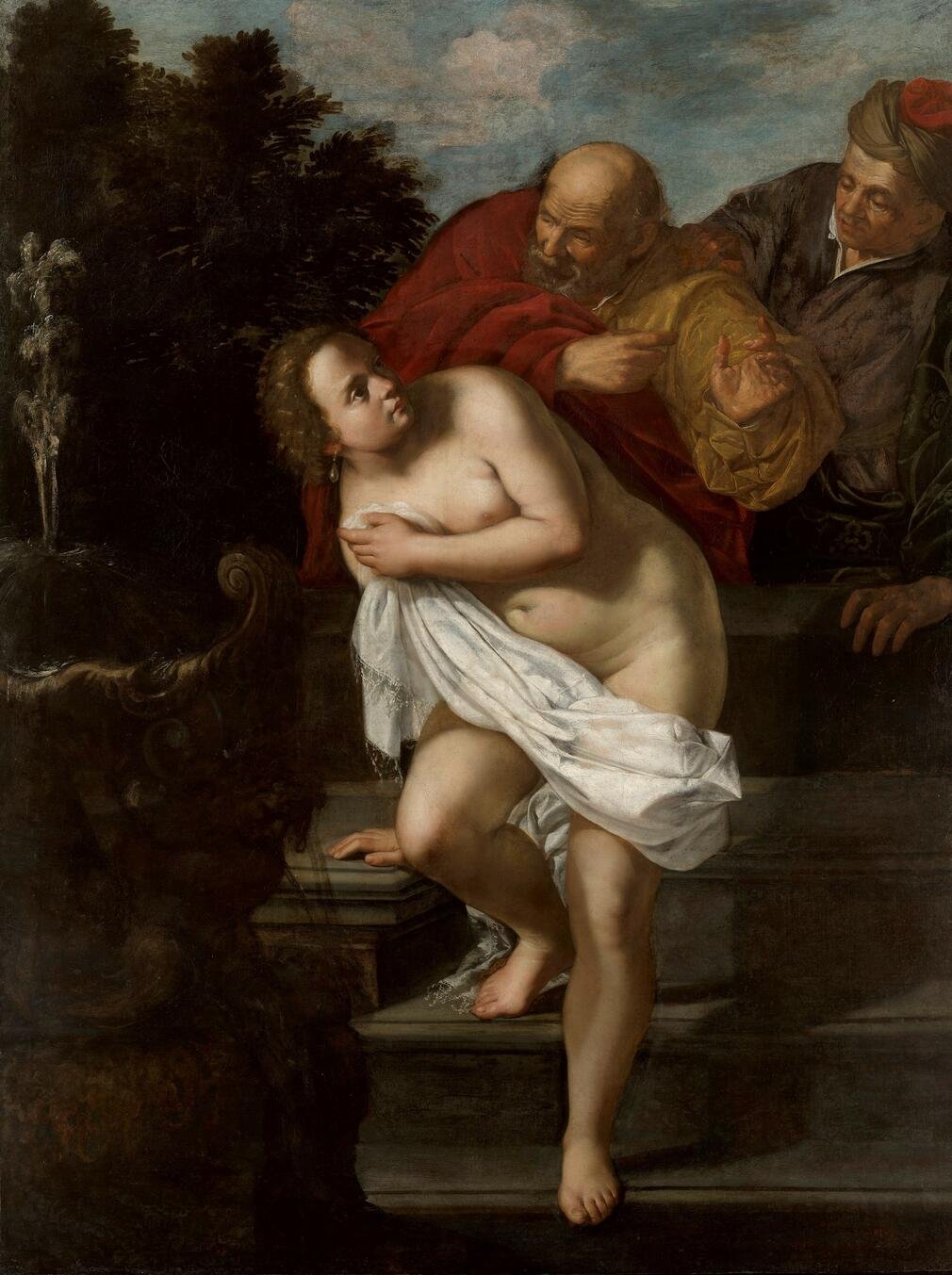

The rediscovered painting, Susanna and the Elders, forms a significant addition to Artemisia’s extant body of work and sheds fresh light on her creative process and her time in London in the late 1630s, working alongside her father at the court of Charles I and Henrietta Maria.

Following extensive conservation, the painting has gone on display for visitors to Windsor Castle. Shown alongside it are Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (‘La Pittura’), considered one of Artemisia’s greatest works, and Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife by her father Orazio Gentileschi, painted during his time in London. The three paintings form a new temporary display in the Queen’s Drawing Room, taking their place alongside other Stuart masterpieces in the Royal Collection.

The rediscovery resulted from work by Royal Collection Trust curators, notably former staff member and art historian Dr Niko Munz, to trace the paintings sold off and scattered across Europe after Charles I’s execution. Seven paintings by Artemisia were recorded in Charles I’s inventories but only the Self-Portrait was thought to survive today, with the others thought lost. However, research allowed curators to match the description of Susanna and the Elders to a painting that had been in store at Hampton Court Palace for over 100 years, attributed to ‘French School’ and in very poor condition. A ‘CR’ (‘Carolus Rex’) brand has subsequently been found on the back of the canvas during conservation treatment, confirming that the painting was once in Charles I’s collection.

Artemisia Gentileschi gained fame across Europe in the 17th century, a time when few women artists were formally recognised. She trained with her father in Rome and later worked in Florence, Naples, Venice and London for aristocratic and royal patrons. Her work fell out of favour in the 18th and 19th centuries, but in the last 50 years she has become known for her powerful and empathetic depictions of women from history.

Anna Reynolds, Deputy Surveyor of The King’s Pictures, said, ‘We are so excited to announce the rediscovery of this important work by Artemisia Gentileschi. Artemisia was a strong, dynamic and exceptionally talented artist whose female subjects – including Susanna – look at you from their canvases with the same determination to make their voices heard that Artemisia showed in the male-dominated art world of the 17th century.’

The rediscovered painting depicts the Biblical story of Susanna, who is surprised by two men while bathing in her garden. When she refuses their advances, she is faced with a false accusation of infidelity, punishable by death, before she is proven innocent. While male artists of the period often presented an idealised or sexualised view of the scene, Artemisia gives great emphasis to Susanna’s vulnerability and discomfort as she twists her body away from the lecherous men. It is a story that Artemisia returned to many times over her 40-year career; at least six compositions of the subject by the artist are known today. The story may have held particular resonance given her own experience of sexual assault, having been raped at age 17 by an artist in her father’s workshop and subjected to gruelling questioning and torture at his trial.

The painting’s history can be traced in a remarkably unbroken line, with records found in every century since its creation. It was commissioned by Henrietta Maria, probably around 1638–9, during Artemisia’s brief time in London when she was likely assisting her elderly father in his work. The 1639 inventory by Abraham van der Doort, Surveyor of The King’s Pictures to Charles I, shows that the painting originally hung above a fireplace in the Queen’s Withdrawing Chamber at Whitehall Palace – a relatively private room used by Henrietta Maria for receiving small numbers of officials, eating and relaxing.

Dr Niko Munz said, 'One of the most exciting parts of this painting's story is that it appears to have been commissioned by Queen Henrietta Maria while her apartments were being redecorated for a royal birth. Susanna first hung above a new fireplace – probably installed at the same time as the painting – emblazoned with Henrietta Maria's personal cipher 'HMR' (‘Henrietta Maria Regina’). It was very much the Queen's painting.'

The painting was returned to Charles II shortly after the Restoration in 1660 and is thought to have hung above a fireplace at Somerset House, home to queens and consorts including Catherine of Braganza and Queen Anne. In the 18th century, as Artemisia’s reputation waned, the painting appears to have lost its attribution. It was moved to Kensington Palace, where it is depicted in a watercolour of the Queen's Bedchamber in 1819 leaning against a wall, suggesting it was considered the work of a minor or unkown artist and not worthy of hanging. It was later transferred to Hampton Court Palace, where at some point it lost its frame, and in 1862 it was described as 'in a bad state' and sent for restoration, at which point additional layers of varnish and overpaint were likely applied.

Since its rediscovery, the painting has undergone significant treatment by Royal Collection Trust conservators. Work included the painstaking removal of centuries of surface dirt, discoloured varnish and non-original paint layers to reveal the original composition; removing canvas strips that were added to enlarge the painting sometime after its creation; relining the canvas; retouching old damages; and commissioning a new frame.

Analysis of the painting during conservation has confirmed the reattribution and given an insight into Artemisia’s working practices. She is thought to have travelled with a stock of tracings or drawings that she used to create new compositions, and conservators found that at least four parts of the painting were also used in previous works, including the Elders’ heads and Susanna’s face. Artemisia must have considered this Susanna particularly accomplished, as she reused elements of the figure in at least three versions of her later painting Bathsheba. X-radiography (used to analyse aspects of a work not visible to the naked eye) and infrared reflectography (used to make underdrawing visible) have also revealed changes that Artemisia made to the composition, uncovering a large fountain that she subsequently painted out with trees.

Adelaide Izat, Paintings Conservator, said, ‘When it came into the studio, Susanna was the most heavily overpainted canvas I had ever seen, its surface almost completely obscured. It has been incredible to be involved in returning the painting to its rightful place in the Royal Collection, allowing viewers to appreciate Artemisia’s artistry again for the first time in centuries.’