London's Turbulent Russian Market

The market for Russian art is one of the strangest in the auction world. It plays out in London – for the quasi-exclusive benefit of Russian dealers and collectors who jet in from Moscow. Its biggest sellers are artists beloved by Russians – who, to international collectors, appear little-known and over-priced. The market is not the preserve of Sotheby’s and Christie’s – but also involves their smaller cousins Bonhams and family firm MacDougall’s, launched in 2004 exclusively to sell Russian art.

THE MARKET FOR RUSSIAN ART is one of the strangest in the auction world. It plays out in London – for the quasi-exclusive benefit of Russian dealers and collectors who jet in from Moscow. Its biggest sellers are artists beloved by Russians – who, to international collectors, appear little-known and over-priced. The market is not the preserve of Sotheby’s and Christie’s – but also involves their smaller cousins Bonhams and family firm MacDougall’s, launched in 2004 exclusively to sell Russian art.

Sotheby’s are long-term market-leaders with a share of over 40%, ahead of Christie’s (25-30%), MacDougall’s (around 20%) and Bonhams (around 5%) – although MacDougall’s and Bonhams have each achieved some of the highest prices in the field: £7.9m for a Roerich landscape at Bonhams, and £7m for a Fechin portrait at MacDougall’s.

Since 2005, by hosting twice-yearly Russian Auction Weeks, London has established its status as the global capital of the Russian art market – to the detriment of New York. It is a market uniquely sensitive to political and economic circumstance. Sales peaked in Winter 2007 at a total £96m. By Summer 2009, in the wake of the global economic crash, sales had plunged threefold, down to £30m. The market recovered gradually until Summer 2014, when sales totalled £64m; then, as Crimea sanctions began to bite, plummeted again... to an all-time low of £16m in Summer 2016. Recovery since then – to £36m in June 2019 – has been tentative. Auction houses are finding major consignments hard to come by. It is not considered a propitious time to sell.

London’s Russian auctions are grouped in twice-yearly clusters in November and June, with sales held on Monday at Christie’s, Tuesday at Sotheby’s, and Wednesdays at MacDougall’s then Bonhams. The lead-in is equally well-established, starting with a Friday evening party organized by the website Russian Art + Culture – held this June at Shapero Rare Books, opposite Sotheby’s, and doubling as the vernissage for an exhibition devoted to Mamuka Didebashvili (born 1968),‘the Georgian Bruegel,’ whose works fuse Flemish humour with a gleaming, Japanese lacquer finish (below).

Russian Art + Culture also produces a Russian Week information booklet (‘Russia,’ for Russian Week purposes, includes the territory of the former USSR). This used to be full of events staged at a plethora of London galleries specializing in Russian art. Alas, most of them no longer exist: Cork Street’s St Petersburg Gallery, Sphinx Fine Art in Kensington, the London offshoots of Moscow’s Regina Gallery and St Petersburg’s Erarta Galleries.... Two non-commercial galleries specializing in contemporary Russian art, Grad and Calvert 22, had nothing scheduled this June; a Yevgeny Fiks exhibition at the venerable Russian culture centre, Pushkin House, had already closed when Russian Week began; while the big Goncharova retrospective at Tate Modern only got underway after it was over.

It all added up to June 2019 Russian Week feeling rather bleak – not helped by a change to its auction geography. Until last year all sales took place within a ten-minute walk of one another in Mayfair: Sotheby’s (above) and Bonhams on New Bond Street, Christie’s and MacDougall’s either side of St James’s Square. Last November, however, MacDougall’s relocated one mile north, to Asia House in Fitzrovia.

One constant, though: Russian Week is party time. All auction houses host drinks receptions to entice prospective buyers to their pre-sale viewings. Christie’s, on Saturday night, have the best cocktails; MacDougall’s, on Sunday, the best music (a live jazz trio). But this June it was Bonhams stood out – by hiring the London Russian Ballet School to perform dances from Stravinsky’s Firebird (above) and complement their small exhibition of Ballets Russes costumes and 22 undated but ultra-traditional Sleeping Beauty costume designs (sold for just over £50,000).

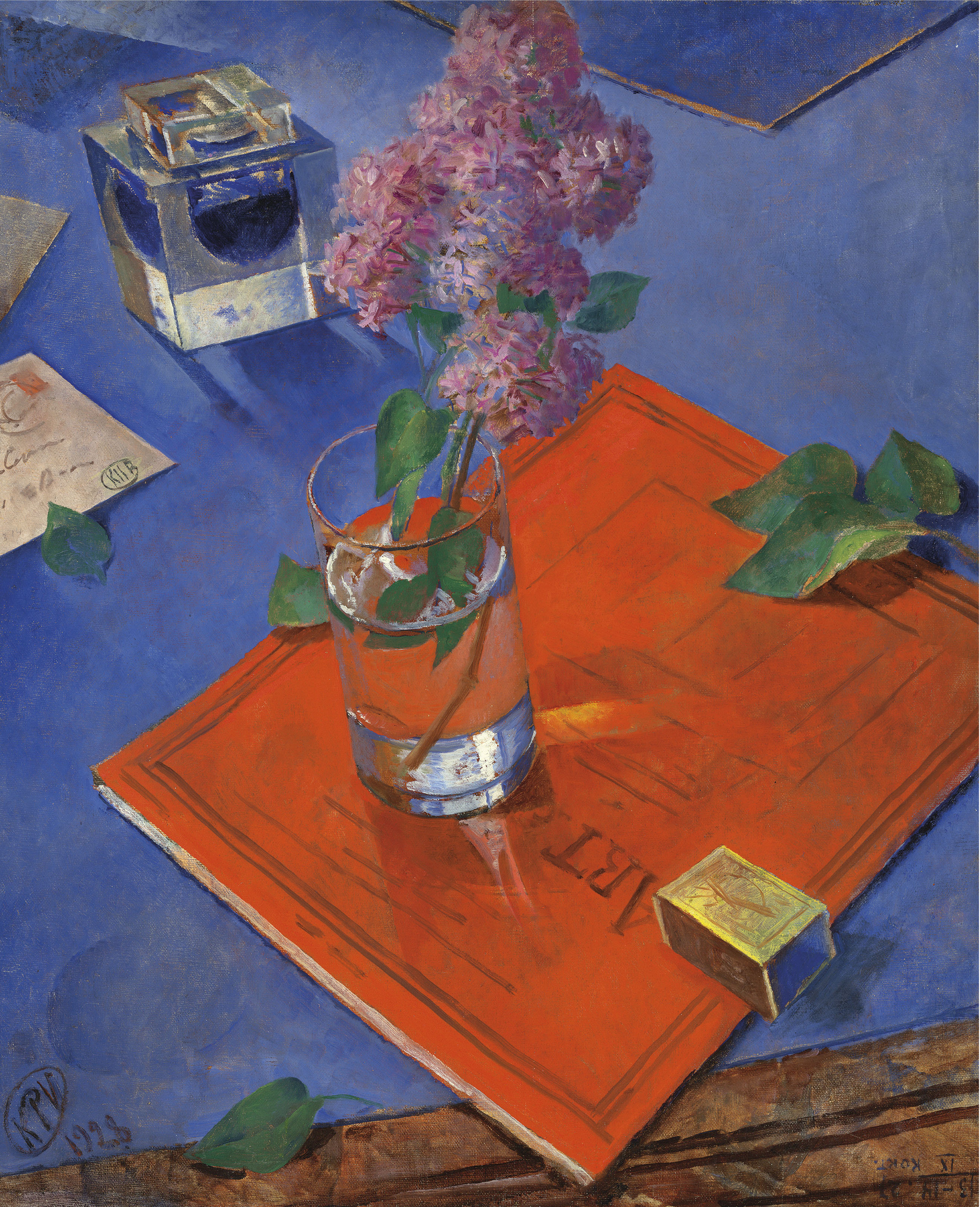

The auctions took place June 3-5, with 1,175 lots available – a far cry from Winter 2007 with its record 2,582 lots. Christie’s, Sotheby’s and MacDougall’s (above) all offered over 300 lots; the first two sold over two-thirds of them, MacDougall’s just under half. Over one-quarter of the auction total of £35.9m came from a 1928 Petrov-Vodkin Still Life with Lilac (see top) whose £9.2m at Christie’s set a record price for Russian Week (the world record price for Russian art at auction, mind you, is $85.8 million – for a 1916 Malevich Suprematist Composition at Christie’s New York in May 2018). The Petrov-Vodkin was bought by an anonymous phone buyer – rumoured to be Petr Aven, head of Alfa Bank and one the world’s leading collectors of the Russian Avant-Garde. The rumour has not been substantiated.

The Petrov-Vodkin was shown in America (Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Chicago) in 1928/9, then at the 1932 Venice Biennale, before being acquired by Italian art critic Giovanni Scheiwiller and consigned for sale by his descendants. It features a sprig of lilac in a glass placed on the red cover of the magazine L’Art Vivant, in front of a crystal Art Deco inkwell on a blue tablecloth. Given the inkwell’s French design, and lilac’s status as a symbol of first love, the picture is doubtless an emotional tribute to Petrov Vodkin’s wife Maria, whom he met in Paris in 1906. Stylistically – with its repetitive sharp angles and combination of squares, oblongs and circles – it is a tribute to Suprematist Malevich.

Sotheby’s responded with a large but unconvincing Still Life (c.1912) by Larionov (above), whose £2.18m price-tag was due less to artistic accomplishment than rarity and cast-iron provenance: it remained in Larionov’s studio until his death in 1964, then was sold in 1968 by New York dealer Leonard Hutton to Los Angeles collector Lionel Bell, who died earlier this year.

The market scarcity of Russian Avant-Garde pictures is fuelling an upsurge in prices for Soviet Porcelain – a term applied to blank plates ransacked from Tsarist palaces and painted with propaganda scenes during the 1920s. Twenty-one of these plates surfaced in London this June, yielding over £1.2m, with a top price of £275,000 at Christie’s for an oval dish painted with a colourful shipyard scene by Stella Vengerovskaya in 1923 (above). Sotheby’s responded with a circular plate evoking the Soviet-Polish War, painted by Vasily Timorev around 1920 (below). It sold for £131,000.

The market for Works Of Art generally relies less on porcelain than on Fabergé – whose Rothschild Egg fetched £8.98m at Christie’s in 2007. Yet Fabergé is another market in the doldrums.

Sale room highlight this June was an ensemble of animal and bird figurines, assembled by Lady Ina Oppenheimer (1899-1971) of South African diamond family fame, that totalled a treble-estimate £817,000, led by a nephrite Frogon £225,000.

Meanwhile the Icon market has been in constant decline since 2010, when over 200 lots were offered during Russian Week. By 2014 that figure had dropped to under 100. This June saw just 50 icons in the salerooms, generating £346,000 (as compared to an all-time high of £4.2m in Summer 2008).

19th & 20th Century Paintings

Many of London’s top Russian prices go to 19th century paintings – principally Ayvazovsky seascapes and Shishkin treescapes. This June Shishkin’s Siverskaya forest scene rated £323,000 at Christie’s. Sotheby’s replied with four hefty-selling Ayvazovskys – led by an 1859 Ship off Cap-Martin (below) at £1.19m, and pursued along the Riviera by his bo’sun Bogoliubov, with a Menton Sunset (c.1885) at £250,000. Other biscuit-tin offerings at Sotheby’sincluded Polenov’s 1883 view of the River Oyat (east of Lake Ladoga) on £699,000 and a Makovsky Boyarina on £250,000.

These artists seldom appeal to international collectors at those sort of prices. Of Russia’s greatest 19th century painters only Levitan, Serov and Vereschagin appear occasionally at auction; the best paintings by Kramskoy, Ge, Quinjy, Vrubel and Fyodor Vasiliev are in museums.

One of the few artists whose pre- and post-Revolutionary output is equally popular is Boris Kustodiev – who was born in Astrakhan near the Caspian, in Russia’s deep south, but spent most of his adult life in St Petersburg, where he assisted Repin on his epic portrayal of the State Council (1902/3). One of the portraits Kustodiev painted for that purpose, featuring rubicond Count Alexei Ignatiev, sold at Sotheby’s for £350,000. In 1917, by when Kustodiev had become confined to a wheelchair with tuberculosis of the spine, he painted a colourful view of Bakrhchisaray in Crimea (below) that landed £1.57m at MacDougall’s – a five-year, 25% return on the £1.26m it made at Sotheby’s in 2014.

A handful of artists thrived under Communism by applying an inventive twist to Socialist Realism.

The most expensive are Gely Khorzev, whose works seldom appear at auction, and the more prolific Alexander Deneika, who turns up in the saleroom far more regularly. This June his late, inconsequential floral Still Life with Phlox (1955) soared to £419,000 at Christie’s.

Other big Soviet names in auction action this June were Georgy Nissky, with an Airfield (c.1965) that landed £212,500, and Yuri Pimenov, with a poetic worksite scene entitled New Districts of Moscow (1975) that made £37,500.

Russian Week also throws up artists whose talent is belied by their unfamiliarity. Take Nadezhda Lermontova, whose posthumous 1914 portrait of fellow-student Varvara Klimovich-Toper (above) made £62,500 at Christie’s.

Or Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva (1871-1955), a Senator’s daughter from St Petersburg who studied with Whistler in Paris in 1898/9, and lived near the Finland Station on Ulitsa Nizhegorodskaya – since renamed Ulitsa Academika Lebedeva in her honour. AOL’s colourful, Vallotton-style, early 20th century woodcuts (example below) rated a double-estimate £90,000, also at Christie’s.

Sotheby’s, meanwhile, had Alexei Arapov (1904-48), whose Self-Portrait with Dog – painted in an elongated style fusing Lyonel Feininger and El Greco (below) – was snaffled for a bargain £3750. Arapov’s father was a high-ranking army doctor and his mother a niece of Leo Tolstoy, but the October Revolution forced the family into domestic exile – spent in a Volga German community near Saratov, where Arapov studied art.

In 1923 he moved to Moscow to work in theatre design, then in 1925 absconded to the West – initially to Paris, where he exhibited alongside Puny, Lanskoy, Goncharova and Larionov before moving to Boston with his American wife in 1930. He acquired U.S. citizenship and converted to Catholicism before dying in a car crash at the age of 43.

Contemporary Art

Although the global auction market is driven by Post-War & Contemporary Art, Russia’s contribution is negligible. Only a handful of living Russian artists, led by Ilya Kabakov and Erik Bulatov, ever appear in international sales. Neither were represented by anything substantial in London this June, leaving Ivan Chuikov (born 1935) in the spotlight with his large, 1989 Hotel Ukraina (below) that earned £175,500 at MacDougall’s – who also took £135,000 for Faibisovich’s KоторыйЧас?(‘What’s The Time?) painted the same year.

Contemporary Art – generally by ‘Non-Conformist’ artists who rebelled against Soviet aesthetics and worked clandestinely – routinely accounts for over 10% of sales at MacDougall’s, who also sold two paintings by the prolific Oleg Tselkov (born 1934), an auction mainstay. Over at Sotheby’s, Tselkov’s pink Woman and Cat (1983), from a U.S. collection, and his green Soldiers & Animal (1984), consigned by the Costakis family, each made £137,500. Bonhams secured £125,000 for his purple Couple with Scissors (1985). Works by Vladimir Ovchinnikov were equally plentiful. Four sold at MacDougall’s, led by Noah’s Ark (2005) at £54,0000. Yet the Pythonesque appeal of this Soviet Surrealist is ebbing. His 1977 Shuvalovo Station (below) sold at Christie’s for £37,500, well short of the $96,000 (around £48,000) its consignor paid for it at Sotheby’s New York in 2007.

Six works from the former collection of Larisa Piatnitskaya (1940-2014), a key figure in the Non-Conformist movement, were offered at Bonhams. Only three sold, all by Vladimir Yakovlev (1934-98), for a modest total of £20,000. Works by Zverev, Bordachev and Larisa’s husband Vladimir Piatnitsky (1938-78) bit the dust.

Thanks largely to Sotheby’s (£1.1m from 27 lots) and MacDougall’s (£927,000 from 32 lots), Russian Contemporary garnered £2.35m this June – around 7% of the Russian Week total. Back in Summer 2008 Russian Contemporary yielded £8.4m, for a 12% share of the market. Today its London flame is kept aflicker by Petersburg émigrée Marina Shtager, with her experimental space for Russian artists at Elephant & Castle, and by two venues in Chelsea: Sofya Abbott’s SAAS Gallery, which recently hosted Olga Soldatova (born 1965) and Valery Chtak (born 1981); and Vladimir Tchaly’s Studio Arud, keen to branch out from interior design into promoting Russian/Ukrainian art – especially Kharkov artist Viktor Gontarov (1942-2009) and the 1960s Leningrad circle of Alexander Arefyev.