There is ample evidence that the portrait on vellum auctioned by Christie’s in New York on 30 January 1998 as ‘19th century German’ is nothing of the sort. Pigment and carbon-14 analyses point to a Renaissance dating – as Christie’s had been advised by consignor Jeanne Marchig (whose late husband Giannino worked as a restorer for the Wildensteins).

There is ample evidence that the portrait on vellum auctioned by Christie’s in New York on 30 January 1998 as ‘19th century German’ is nothing of the sort. Pigment and carbon-14 analyses point to a Renaissance dating – as Christie’s had been advised by consignor Jeanne Marchig (whose late husband Giannino worked as a restorer for the Wildensteins).

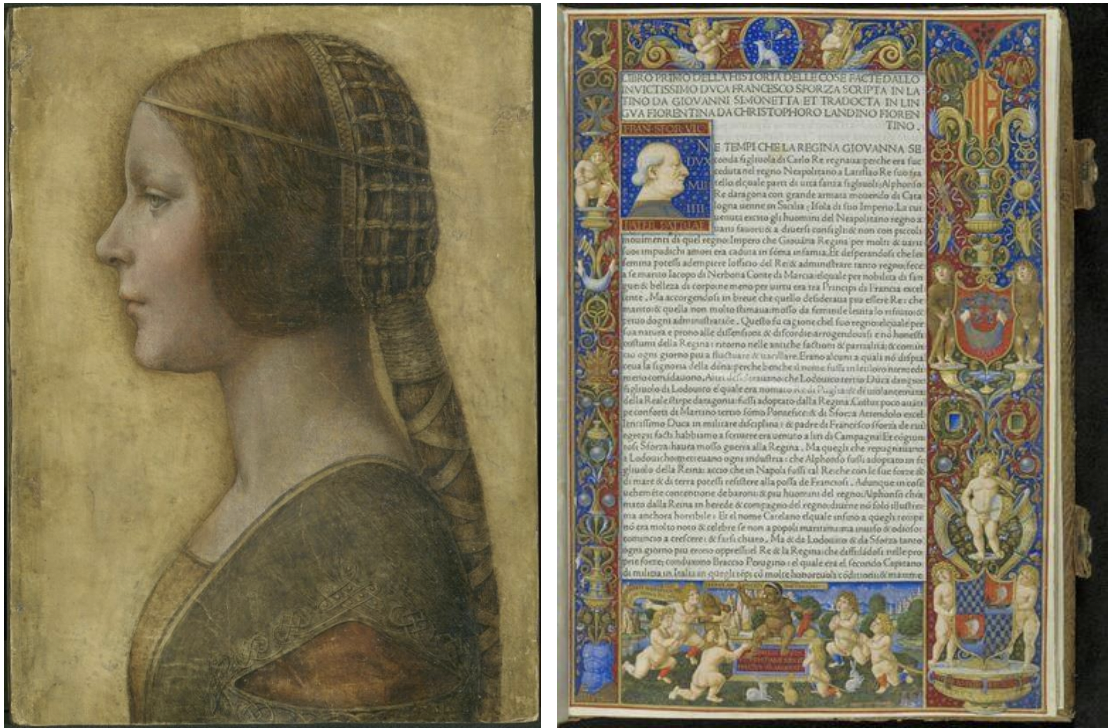

Stylistic sophistication points an artist of genius: the portrait is a technical tour de force that looks like a painting but was created with ink and red, white and black chalk. The magnificently subtle eye, ultra-observant detail (five hairpins in the pony-tail can only be spotted with powerful magnification) and the work’s left-handed authorship all point to… Leonardo da Vinci.

The work has been assigned to Leonardo by Martin Kemp, Emeritus Professor of Art History at Oxford University, and Europe’s leading Leonardo specialist; Nicholas Turner, former Curator of Drawings at the British and Getty Museums; Mina Gregori, Director of the Longhi Foundation in Florence and doyenne of Italian art historians; and Alessandro Vezzosi, founder of the Museo Ideale Leonardo da Vinci in Leonardo’s native town of Vinci.

The original purpose and location of the portrait have been identified: its dimensions, and the position of three stitch-holes down the left-hand side, correspond perfectly with those of an incunabulum in the Polish National Library, Warsaw. The book is known as the Sforziada and was one of four de luxe, illuminated copies of a biography of Francesco Sforza, the first Sforza Duke of Milan (1450-66), commissioned by his son Ludovico (1452-1508) – better known as ‘Il Moro’ and de facto ruler of Milan from 1480-99 (initially as Regent).

The illuminated frontispiece (top right), by Leonardo’s Sforza Court colleague Gianpietro Birago, indicates that this copy commemorated the wedding of Il Moro’s illegitimate daughter Bianca (1483-96) to Galeazzo Sanseverino – Il Moro’s right-hand man, army captain and effectively regime n° 2 – in June 1496. The portrait and frontispiece were to be found on successive right-hand pages near the front of the volume.

The dark-skinned cherub featured centrally in Birago’s tongue-in-cheek allegory (below), raising his finger to Heaven, represents Duke Ludovico Sforza – ‘Il Moro’ meaning ‘The Moor.’

The dusky female, with blonde hair and under-developed breasts, represents his 13 year-old daughter, Bianca. The cameo tied around her forehead makes reference to Leonardo’s portrait La Belle Ferronnière (now in the Louvre).

She is arm-in-arm with her husband-to-be, Galeazzo Sanseverino – whose spreadeagled limbs make reference to Leonardo’s drawing Vitruvian Man.

Il Moro is effectively marrying them, and holds a cardinal’s hat he has ‘borrowed’ for the occasion from the tonsured cherub kneeling at his feet – who represents Galeazzo’s brother, Cardinal Federigo Sanseverino.

THE SCOPETTA

The most curious aspect of Bianca’s portrait is the triangular shoulder aperture to her dress – which shows up more distinctly in a digitally enhanced version of the work (below middle) produced by Lumière Technology of Paris (the portrait’s vellum support having severely yellowed with age).

The nearest equivalent in Renaissance portraiture is to be found in the famous Portrait of a Lady in Milan’s Pinacoteca Ambrosiana – attributed to Ambrogio de Predis (who collaborated with Leonard on The Virgin of the Rocks), and doubtless featuring Bianca’s slightly older cousin, Anna Sforza (1476-97).

But what is the significance of Bianca’s strangely shaped triangle and the elaborate embroidery surrounding it? Is it purely decorative, or is it linked to the identity of the sitter, and/or the occasion the portrait commemorates?

Another portrait with a shoulder aperture (above right) provides a clue. It shows Bianca’s father, Il Moro, and commemorates his investiture as Duke of Milan by the Holy Roman Emperor in 1495. Its gold triangle features the eagle and viper of the House of Sforza (right). As with the De Predis portrait – but unlike Bianca’s – the aperture is shaped like a regular triangle.

There is every chance, then, that the embroidered triangle on Bianca’s dress is not just decorative but a means of identification. In fact, its shape and outline recall those of Il Moro’s favourite personal device: a small-handled clothes-brush known as a scopetta (sometimes translated as ‘whisk-broom’).

The scopetta was originally the emblem of Il Moro’s father Francesco, the dynasty-founding hero of the Sforziada. Il Moro obtained permission to use it – from his widowed mother, after Francesco’s death – while still a teenager. Shown below are the scopetta as used on a silver coin during Il Moro’s reign (left) and in a painting of Il Moro celebrating his recovery from serious illness in 1488 (right).

Il Moro is shown sporting a silver scopetta on his chest (alongside his ducal chain) in his ‘Giovio’ portrait now in Florence’s Uffizi Gallery (above left). A scopetta made of pearls and precious stones was worn as a hair brooch by Il Moro’s niece Bianca Maria in her 1493 portrait by Ambrogio de Predis (below), marking her wedding to Maximilian Habsburg, the Holy Roman Emperor. The scopetta underlines the sitter’s kinship with and allegiance to Il Moro.

The embroidered triangular aperture on Leonardo’s portrait of Bianca, then, identifies her as Il Moro’s daughter.

Like the Sforziada volume that originally included Leonardo’s portrait, the scopetta is also to be found in Poland.

In 1518 Bona Sforza, Il Moro’s great-niece, married King Sigismund I of Poland in Cracov, taking the Sforziada with her – along with a bejewelled scopetta. Both were doubtless presented to her mother, Isabel of Aragon, Dowager Duchess of Milan, by Il Moro when he fled the advancing French in 1499. The scopetta (below left) appears in the coronation portrait of Bona’s daughter Anna (below right) from 1576, when she became Queen of Poland upon her wedding to King Stephen Bátory. The scopetta dangles from a long chain, at the level of her right ankle.

A scopetta is also quoted in the Renaissance-era Sigismund Chapel in Cracov that served as the Polish royal mausoleum. It appears at the foot of a decorative panel (below centre) next to the tombs of Bona Sforza’s husband Sigismund I and son Sigismund Augustus – the work of Florentine sculptor Santi Gucci (c.1530-1600). Gucci’s use not only of a scopetta, but also of a mask and leafy font that seem directly inspired by Birago’s Sforziada frontispiece, suggest he had access to the Sforziada taken to Poland by Bona Sforza – presumably courtesy of her daughter Anna. Did the volume still, at the time, contain Leonardo’s portrait?

There is intriguing circumstantial evidence.

After Jeanne Marchig’s death in 2013 I was invited by her partner Bryan Deschamps to explore the basement of her house near Geneva.

We came across a leather folder embossed with the Gucci family rose emblem, and bearing the handwritten inscription Libro del cassierato di ms Gio. Battista Gucci del’año: 1599 (‘Accounts Register of MS Gio. Battista Gucci, 1599’).

According to his widow Jeanne, Giannino Marchig used to keep his fragile Renaissance portrait inside a folder. The images below, which are to scale, suggest that the dimensions of the Gucci folder would have been ideal for the purpose.

Was the portrait removed from the Sforziada in the late 16th century, gifted by Queen Anna to Santa Gucci, then sent back to Italy – where it was placed in a leather folder... with both portrait and folder acquired by Giannino Marchig 350 years later?

THE CHAIN NECKLACE

The triangular aperture and knotwork embroidery are indeed the keys to interpreting this work – providing they are viewed as a whole, not separately; and providing you remember you are looking at a book – which can easily be turned upside-down.

The portrait, like all the pages, was slightly trimmed when the book was first rebound (probably ahead of Bona Sforza’s wedding in 1518). The complete knotwork embroidery, as it would originally have appeared if viewed upside down, is shown in stylized form below left. It forms the outline of a stylized chain necklace ending in a medallion: that of the Ordre de St-Michel – France’s most prestigious award – bestowed upon Galeazzo Sanseverino by King Charles VIII in Lyon on 6 April 1494. This award is not just recorded in historical accounts, but also in a manuscript copy of De Divina Proportione (now in Milan’s Biblioteca Ambrosiana) presented to Sanseverino by its author, Luca Pacioli, in 1498 – whose front page features Sanseverino’s personal coat-of-arms (below right) flanked by the initials G Z for (Galeazzo) and ringed by a depiction of his Ordre de St-Michel necklace.

A comparison with the Milanese effigy of French commander Gaston de Foix (below left), slain at the Battle of Ravenna in 1512 and another recipient of the Ordre de St-Michel, shows that such chains took of the form of interlacing Vinci-like knots (above centre).

Leonardo’s portrait, therefore, subtly evokes Bianca’s dual allegiance to her husband and to her father – echoing the message of Birago’s Sforziada frontispiece.

But what of Bianca herself? Is her own status evoked in Leonardo’s portrait?

THE CLIFFS

In 1489 Bianca Sforza was officially ‘legitimized’ as Il Moro’s daughter, betrothed to Galeazzo Sanseverino – and made Lady of Bobbio, a small, ancient town 50 miles south of Milan as the crow flies. Il Moro had captured Bobbio from the Dal Verme family in 1485. It lies in the Trebbia Valley, lauded by Ernest Hemingway as one of the most beautiful in the world.

Back in the 15th century Bobbio was of strategic and commercial importance – straddling the Via del Sale (Genoa Salt Road) and the Cammino di San Colombiano (Pilgrim’s Way from Strasbourg to Rome).

Pilgrims stopped in Bobbio because of its Abbey, founded in 614 AD by St Columbanus from Ireland on land granted by King Agilulf of the Lombards. The Irish monks who followed St Columbanus to Bobbio included St Dungal, who died in Bobbio around 828 and bequeathed 27 volumes to the Abbey Library – which, by 900 AD, had swollen to 600 volumes. Medieval Bobbio was renowned as one of the most famous manuscript centres in Christendom – inspiring Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose.

Its school of illumination perpetuated an ornately Gaelic approach to manuscript decoration replete with interlacing patterns whose bewildering complexity (examples below) begs comparison with Leonardo’s knots.

There is no record that Leonardo da Vinci visited Bobbio but, given his love of books and of striking scenery, it would be mighty surprising if he did not. And Bobbio was in the news at Il Moro’s court in 1493: that year the humanist scholar Giorgio Merula removed some of the Abbey’s codices to Milan. Many more (now in Turin, the Vatican, Paris, Madrid, Berlin and above all the Ambrosiana) remained in Bobbio, including the Venerable Bede’s 9th century Liber de Computo (Bobbio Computus).

There is nothing in Bobbio today that evoke its wondrous manuscript past, but some of the old Abbey stonework and funeral monuments are preserved in the town museum, swathed in intricate knotwork similar to that found in ancient Gaelic manuscripts.

Some of this stone knotwork is strikingly similar to that in Leonardo’s Portrait of Bianca Sforza – whether along the fringe of her caul (below left) or in her shoulder embroidery (below right).

The most glorious reminder of Bobbio’s past is the eleven-arched, 300-yard medieval bridge across the Trebbia known as the Ponte Gobbo (Hunchback Bridge). With its gentle curves and eye-soothing proportions, this is a Taj Mahal among bridges. Some believe it to be the bridge Leonardo painted into the background of his Mona Lisa.

Bobbio’s surrounding hills are peppered with unique chalky cliffs shaped like flattened triangles. They bring the curious shoulder aperture in Leonardo’s portrait of Bianca Sforza irresistibly to mind.

THE TOWER

Just outside Bobbio stands Il Torrione del Trebbia, an agriturismo that stands intriguingly close to one of the triangular chalky cliffs.

Much of the agriturismo building (below left) is tasteful 20th century pastiche, but the tower at one end is medieval – its architecture not dissimilar from Bobbio’s 14th century Castello Malaspina (below right) where the Lady of Bobbio and/or Leonardo da Vinci presumably once stayed.

The tower of the agriturismo was doubtless built to survey the northern approach to the Bobbio along the Trebbia Valley. This is the view:

And this (above) is the view from tower looking south towards Bobbio. The Castello Malaspino stands in the highest part of the town, and can be discerned mid-picture, three-quarters to the right.

Here is a view of Il Torrione del Trebbia from across the Trebbia River, from afar and in close-up:

The chalky cliff beneath the agriturismo is strikingly similar in shape to that of Leonardo’s aperture in his portrait of Bianca Sforza. Could his quirky triangle have been meant to evoke one Bobbio cliff in particular, rather than the surrounding cliffs in general?

Given the overgrowth of trees and bushes on the cliff beneath the agriturismo, however, it is hard to determine the cliff’s precise outline.

It seems, however, implausible that Leonardo should have used knotwork embroidery to evoke both Il Moro (his scopetta) and Galeazzo Sanseverino (his Ordre de St-Michel)… but not Bianca.

What, for instance, could be the significance – as far as Bianca is concerned – of the elongated oval topping the triangular embroidery that represents the handle of Il Moro’s scopetta and the medallion dangling from Sanseverino’s chain?

In other words: What protrudes above one of Bobbio’s chalky triangular cliffs?

I contacted the owner of Il Torre del Trebbia, Gian Marco Govi, to ask him for information about the history of his Torre (tower). Signor Govi said he had no such information himself, but kindly offered to escort me to the Bobbio Municipal Archives.

I arrived in Bobbio from Siena, driving up the Mediterranean then leaving the motorway after La Spezia, and heading inland along the enchanting Vara River valley to Varese Ligure: another town of significance in the history of Sforza Milan. It was visited by Il Moro in July 1479, along with his brother Sforza Maria and their chief condottiero (mercenary captain) Roberto Sanseverino (who was also their cousin, and Galeazzo’s father). The brothers had spent two years in exile – Il Moro in Pisa, Sforza Maria in Bari, his ducal fiefdom in the heel of Italy – following the assassination of their elder brother Galeazzo Maria in 1476. Meanwhile Galeazzo Maria’s widow, Bona di Savoia, had assumed power as Regent in the name of her seven year-old son Gian Galeazzo.

Il Moro, Sforza Maria and Roberto Sanseverino tarried at Varese Ligure – presumably staying in its muscular castle (right) – awaiting reinforcements from Naples, sent by King Ferrante (who had created Sforza Maria Duke of Bari in 1464). The soldiers were due to land at La Spezia before proceeding with them to Milan, where a coup d’état would propel Sforza Maria (who was a year older than Il Moro) into ducal office. However, in Varese Ligure, Sforza Maria suddenly died. Poison and Il Moro were naturally suspected.

Il Moro, Roberto Sanseverino and their Neapolitan troops proceeded to Milan via a tortuous incognito route over the mountains to Bobbio, before wheeling west to Tortona and heading north along the Scrivia Valley to Castelnuovo (a fortified town granted to Roberto Sanseverino by Galeazzo Maria in 1474) and fording the Po a few miles further on. The ensuing coup duly brought Il Moro to power – initially in a joint regency with his brother’s widow Bona but soon, after elbowing her aside, in his own strongman right.

The 70-mile road from Varese Ligure to Bobbio is one of the wildest, most arduous and spectacular in Europe: a never-ending succession of pot-holes and hairpin bends, rising in places to 5,000ft, with not a petrol station in sight. I arrived at the Torrione del Trebbia at 7 o’clock. Night had fallen and the lights of Bobbio were twinkling in the valley below.

Next morning Gian Marco Covi escorted me to the Municipal Archives, housed on the top floor of Bobbio’s 17th century Palazzo Comunale, or town hall (below left). The archives are stored in slapdash fashion on metal shelves in an attic under the roof (below right).

Despite assurances from the Chief Librarian that the archives only dated back to around 1800, I came across three boxes containing far older material – some of it from the 15th century. One manuscript (below left) was, excitingly, written on 7 June 1496, a fortnight before Bianca’s wedding – but sadly does not appear to contain any mention either of Bianca or affairs pertaining to the House of Sforza.

Meanwhile Gian Marco had found a huge cadastre of Bobbio, drawn up in the early years of the 19th century (below right).

We honed in on the page (below left) featuring his own property. The Torrione del Trebbia is a few inches up from the Trebbia River, shown in green (below centre). The Torrione is numbered 43 and, to my surprise, named not as Il Torrione del Trebbia but as… La Morina.

The fact that La Morina sounds like a female diminutive of Il Moro may be mere coincidence but, knowing Leonardo, and knowing the obsession with puns and wordplay at Il Moro’s Renaissance court, probably isn’t.

Either La Morina was the name given to the tower because it belonged to Il Moro’s daughter – or the tower was already called La Morina, and came to Leonardo’s attention because the name sounded like a little female Moor… of the sort depicted by Birago in his Sforziada frontispiece.

If Leonardo did indeed refer to La Morina in his Bianca portrait, could it have been in the form of the elongated oval at the apex of his knotwork embroidery – as a stylized tower atop a triangular cliff?

I had a hunch that Leonardo might have made his portrait of Bianca while they were in Bobbio – perhaps at the top of the Castello Malespina, from where the tower of La Morina could presumably be seen.

I discovered with Gian Marco that La Morina can indeed be seen from the Castello Malespina. You don’t even have to climb to the top: there is a perfectly clear view of the tower from the castle terrace.

What’s more, the tower is silhouetted against the skyline, protruding distinctly above the surrounding trees:

This is the only place in Bobbio where the tower of La Morina stands out against the sky.

The minute you go downhill towards the town centre, the tower appears to nestle within, rather than soar above, the surrounding hillside:

Neither of these two images, however, shows the tower centrally positioned atop its cliff.

Is there any site in Bobbio from which such a view is apparent?

I sought inspiration by taking a stroll along Bobbio’s beautiful old bridge – the one supposedly immortalized by Leonardo in Mona Lisa, and crossed by many a pilgrim down the centuries.

I took two photographs at the far end of the bridge.

One shows the Trebbia Valley looking north; the other gazes back over the bridge towards Bobbio (with the Castello Malespina emerging like a chunky cube to the right of the taller church tower).

The view down the Trebbia Valley looks rather more interesting through a zoom lens, bringing into view the tower of La Morina atop its chalky cliff:

If we imagine away the trees and scrub that have invaded the cliff down the ages – and Signor Covi, on whose land the cliff stands, has now promised to do so – it becomes apparent that the tower of La Morina is indeed positioned at the cliff’s apex.

And that the form of this triangle bears a convincing resemblance to the shape of the shoulder aperture in Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait.

Above, conversely, are the Ponto Gobbo and Castello Malaspina as viewed from La Morina. Both the castle, and the far end of the bridge, are precisely the same distance (800 metres) as the crow flies from La Morina. Again: maybe coincidence, maybe not. Also worth noting: if a crow flies from the far end of Bobbio bridge to the tower of La Morina, and continues flying in a straight line, it will land in… Milan.

– SIMON HEWITT

author of Leonardo da Vinci and the Book of Doom (Unicorn Publishing 2019)