Interview with Dr. Cyrus Abbasian: Unveiling the Unconsciousness of Art

"As a psychiatrist I cannot help but analyse what emotions, feelings and thoughts the artist was having or is conveying through their art. Empathy is a crucial skill for all psychiatrists and I try to understand and empathise with the artist through their art".

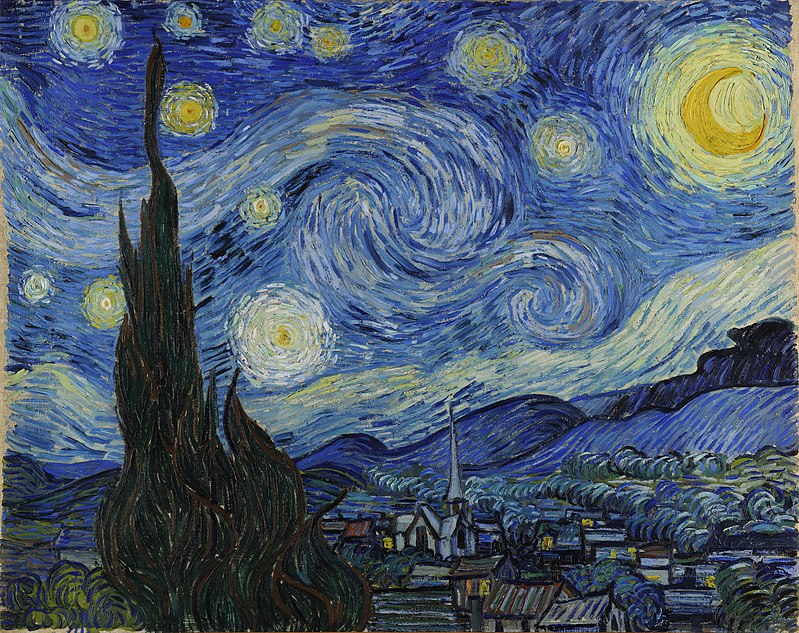

Image: Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night, 1889

ArtDependence (AD): Have you always been interested in art and what attracts you the most?

Dr. Cyrus Abbasian (CA): I am a general adult and addiction consultant psychiatrist, practicing in London for 20 years, and have always been interested in the arts. There is a much-recognised overlap between mental illness and creativity. We tend to treat patients in distress and so I am interested in how art is used to convey this distress. Since I was a student I have been a regular on the London art scene. I am no expert and have had no formal training in the arts. At school in Iran we had Persian calligraphy lessons, which is a skill I have further developed. If there is a quote or piece of poetry that I like, I write it down in my own.

Dr. Cyrus Abbasian, image courtesy to Dr.

AD: What are your personal preferences? Is there a particular piece of art that has had a strong influence on your mind?

CA: As a student I became interested in artists such as Munch and Van Gogh, and in particular have taken interest in those artists who are known to have struggled with mental health issues and portrayed this in their works. I have listened to many patient stories and their narrative is very important in order to establish a diagnosis.

In works of art I try to elicit the same narrative – the symptoms that may be portrayed in an image, or through the style and the colouring used. For example, the image may portray self-harm or psychosis, colours used could show mania or depression, and the style could indicate dementia.

Vincent van Gogh, Sorrowing Old Man ( At Eternity's Gate), 1890

This image epitomised the time I was training in old age psychiatry. Many of our patients were in so much sorrow. Old age is a period of losses - employment and savings, spouse and friends, physical health, cognition and mental wellbeing. Many of our patients were lonely and isolated, and getting them socially active was a lifesaver for many.

AD: Where do you like to go to see art?

CA: Tate, Saatchi, the Royal Academy and anywhere really that has an interesting exhibition. There are so many venues in London. Some smaller, less-known galleries also show interesting exhibitions. Also medical exhibitions at the Wellcome Institute, the Science Museum and even the British Museum are very interesting. Medicine is as much an art as a science and many doctors are active in the arts.

AD: Do you use art in your professional psychiatric practice?

CA: We have art therapy that is an important tool, especially for patients who have difficulty expressing themselves verbally. Sometimes patients show me their works of art that I encourage them to develop and publish.

Idleness remains an issue with many of our patients. I encourage them to fill their time attending galleries in London and being active as an artist that is therapeutic. We also publish the works of our patients that does wonders for their well-being and self-esteem.

AD: It’s a well-known fact that art elevates certain emotions and makes people feel alive. What triggers these emotions?

CA: I find it relaxing to go to art galleries and sometimes visit a particular exhibition several times. It is meditative! It helps me to think and brainstorm, and I usually write down ideas that later develop. It also motivates me to work.

As a psychiatrist I cannot help but analyse what emotions, feelings and thoughts the artist was having or is conveying through their art. Empathy is a crucial skill for all psychiatrists and I try to understand and empathise with the artist through their art.

AD: Unconscious and transpersonal aspects of the human experience often catch the public’s attention. A lot of classical and contemporary artists attempt to communicate basic human states like tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on. Why do you think the topic of human suffering, like in Francisco Goya’s works is so appealing to the public?

CA: Goya is shocking to so many people now, even those tech-savvy in the Internet age that have access to almost any image. It portrays raw primal horrors that humans inflict on one-another. We have evolved as highly intelligent primates who use violence as an important method of protecting our communities and ourselves.

Francisco Goya, Witches in the Air, 1797

Culture has created systems and laws that prevent and punish these primeval acts of aggression, so I am not surprised that people are interested in arts portraying violence or in experiencing violence through activities such as gaming or watching violent films.

AD: Or Munch’s Scream, that depicts a genuine hysteria and was sold for a record price of 120 million USD at Sotheby’s in 2012: why does this picture have such a strong impact on the art market?

CA: One of the most remarkable exhibitions I attended was Munch by Himself at the Royal Academy in 2005. His work was displayed chronologically as his life story and you could observe his mental state fluctuating.

Edvard Munch, 1893, The Scream

To me his Scream is a mental breakdown, or medically described as an acute stress reaction. This could affect anyone secondary to stress. It is like a switch in the brain being turned off and the usual faculties that we take for granted, such as thinking, planning and acting no longer work. Sometimes all that can be done is to scream!

AD: Do you think these kind of influential works could be created under certain conscience-manipulating methods like drug or alcohol use? Or is it about the mental disorders of the artist?

CA: There is a lot of evidence of the overlaps between mental illness and creativity. According to many evolutionary theories, the reason that we have so much mental illness is that the relevant genes leading 'madness' also lead to creativity.

Some drugs can bring about similar symptoms as mental illness. Also they can reduce the inhibitions that can be a hindrance to creativity. As a psychiatrist I would never encourage taking drugs or alcohol that could ultimately cause much damage.

AD: How can one distinguish a mentally disordered artist’s work from healthy creative? Could you please give specific examples?

CA: I do not believe it is possible unless you read the artist’s description of their work. Even if mental illness is clearly depicted in the work, such as self-harm, you would still need this explanation. The Maudsley has many examples of patient works.

AD: What is creativity?

CA: Evolutionary theories inform us that this is an important part of the human selection process, especially when it comes to managing change. People who are creative tend to think ‘outside the box’ and bring new ideas that can sometimes enhance the survival chances of both the individual and the groups that they belong to.

As we are no longer hunter-gatherers and have developed culture this creativity is now mainly manifested through the arts. This is the best way that I can describe creativity.

AD: What is the impact of colour on the human mind? And how could you describe the response to colour and emotional behaviour?

CA: Broadly speaking, bright lively colours could indicate mania and gloomy darker colours depression. We all have heard of Picasso’s “blue period” when it is thought he suffered from depression.

Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1880

You can see signs in Van Gogh’s drawings in terms of colour patterns and link this to his mood; his sunflowers are very bright and colorful for example. It is recognised that he suffered from bipolar affective disorder meaning that his mood fluctuated to elation or to depression.

AD: And what about “Starry Night”? It looks fascinating, mysterious and very beautifully painted in details. But of course there is a certain state of mind of the artist behind it. How would you comment it?

CA: I really can’t say more than what you have written already. It’s very tranquil and probably he was in a peaceful state of mind when he drew it.

Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night, 1889

AD: Let’s take for instance the famous abstract expressionist like Mark Rothko, who was influenced by Jungian psychology of unconscious thoughts, “that grow up from the dark depth of the mind like a lotus”. Rothko’s “floating” colour-blocks were to connect with humanity on a deeper level. What was he speaking to, and did he succeed from your point of view?

CA: This is too specific for me to answer. As a psychiatrist I tend to see patients at their worst and so the art that they produce often conveys distress and even a macabre content. It, however, can be cathartic for both the artist and the viewer.

Mark Rothko, Orange and Yellow, 1956

AD: What about the impressionists, players of light and colour, like Monet? Is it always about straightforward transparency of mind?

CA: I would want to speak to Monet himself. Art therapists are fortunate as they get a firsthand descriptive account from their patients in relation to the works that they have produced.

AD: Speaking about the commercial aspect of art, art being sold. Could you name the main tools (except those discussed above) that sell art? And what are the characteristics of a long-living art piece, which could be invested in?

CA: Art is priceless. By that I do not mean its monitory value. Ridiculous sums paid for a piece of art do not add to its aesthetic value. I see so much value for example, in my patients’ drawings that you simply cannot put a price on.

Two important examples are Bryan Charnley, a patient with schizophrenia and William Utermohlen, who was affected with Alzheimer’s.

Bryan Charnley, Self Portrait Series, 19 July, 1991

Through a series of self portraits they depicted how their condition led to the deterioration of their mental state.

AD: What is your most unforgettable experience unveiled by art?

CA: Too many! Some of the best recent exhibitions I have been to include All Too Human at Tate Britain, which included works of Francis Bacon and Modiglianiat Tate Modern that was displayed chronologically culminating in his death due to addiction.