(in)between the lines of narration with Alvaro Urbano

Earlier this month, Alvaro Urbano presented the latest segment of his on-going project, “My Boy, with Such Boots we may Hope to Travel Far”. The show took place in the city of Turin, in a location that is both highly visible and highly inaccessible: the very top of the Mole Antonelliana, the city’s landmark building.

Earlier this month, Alvaro Urbano presented the latest segment of his on-going project, “My Boy, with Such Boots we may Hope to Travel Far”. The show took place in the city of Turin, in a location that is both highly visible and highly inaccessible: the very top of the Mole Antonelliana, the city’s landmark building.

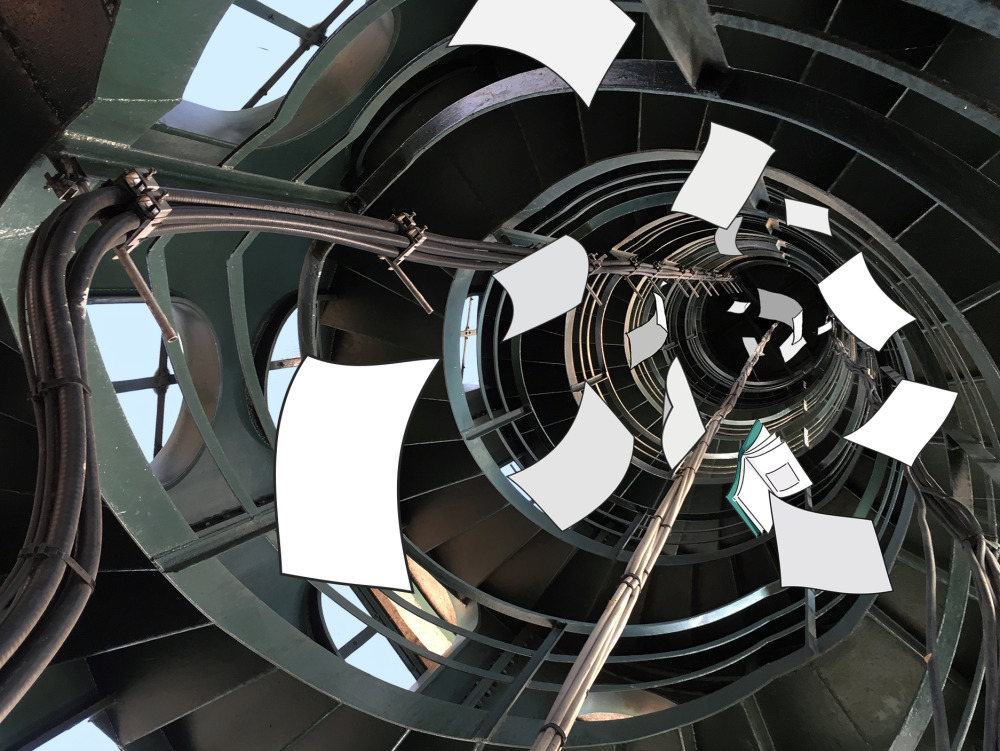

“The Mole”, as most call it, measures 167.5 meters – but it wasn’t always meant to be this tall. During the years of construction, architect Alessandro Antonelli kept modifying the design to reach ever-new heights. In 1889, the building was finally completed after numerous costs and controversies. Now, the Mole houses the Museo Nazionale del Cinema, which (thanks to the altitude of the building’s lengthy steeple) holds the title for world’s tallest museum.

Urbano’s project, “My Boy, with Such Boots we may Hope to Travel Far”, has a very precise context: Jules Verne’s epic “Journey to the Center of the Earth.” Verne’s book deals with the mentioned pursuit, undertaken by Professor Otto Lidenbrock, a character who (much like the Mole’s Alessandro Antonelli) zealously sought to conquer vertical distances. In the book, the Professor and his nephew come across a coded note written in runic script which, when deciphered, indicates the location of a passage to the centre of the earth. Urbano’s project involves taking these runes, giving them shape (as sculptures), and positioning them in different parts of the world – inviting anyone to stumble upon them, much like the Professor and his nephew did.

The title of the show at the Mole – “I” – refers to the last runic letter of the script. However, it also refers to the first person singular pronoun, which is indicative of the particular viewing mechanism of the show: for only one person was allowed to journey to the top of the Mole. Given the participative particularities of the show, it made sense for Urbano to partner with the curators of Treti Galaxie, relative newcomers who are making a name for themselves through unconventional curating practices. Their partnership with Urbano led to a show that was infused with theatricality: they planned it so that forty people would be chosen out of all applicants, to arrive at the base of the Mole and receive a chocolate bar each – only one of which contained a golden ticket. The single winner ascended to the exhibition, while the rest of the participants remained at the bottom, listening to an extract from Verne’s classic.

The Mole Antonelliana is built as a four-faced dome structure – meaning that from the ground floor you have an open view of all four sides arching inwards, leaving only enough space in the middle for an elevator to go through – a clear glass elevator, of course. This was the first step in the journey for the winner of the golden ticket. She went up, looking down, while the others saw her rise, from the ground. The experience of seeing her ascent was accentuated by the words of Verne - or rather, the words of the Professor’s nephew, as he describes his own trek to the top of a similar spire. In preparation for descending great distances, Professor Lidenbrock insisted that they learn to overcome vertigo (“You need to take lessons in precipices!”) by scaling a dizzying, spiral staircase, “protected by a thin rail, with the steps getting ever narrower, apparently climbing up to infinity (…)”

“Journey to the Center of the Earth” was published in 1864, and the story itself takes place a year prior – the same year, in fact, in which construction works began for the Mole Antonelliana. Throughout history we’ll always encounter these type of coincidences among contemporaries: individuals who envision similar possibilities. Through a careful construction of bricks or words, Verne and Antonelli both crafted entirely new vantage points – new perspectives that took us in contrasting yet complementary directions. Could they ever have imagined that their worlds would meet in this way? When it comes to Urbano’s project, context is everything, but it is not restrictive. When-and-if-ever we come across Verne’s runes, in some part of the world, like the Professor and his nephew we are not expected to know what they are, but we are encouraged to wonder.

The following is an interview with Alvaro Urbano, and the curators and co-founders of Treti Galaxie, Ramona Ponzini and Matteo Mottin.

Maria Martens: The show “I” at Mole Antonelliana is conceived for a single spectator, and it is part of an ongoing project that will be situated throughout the world. It is not necessarily impossible for someone to experience the project in its entirety – if they are willing to trace your steps wherever you choose to go - but it is not very likely to happen. As the creator of this project, you are the only one who will have the most complete experience of this work. Couldn’t we say, then, that the overall project (“My Boy, with Such Booth we may Hope to Travel Far”) is also conceived for a single spectator? As the project progresses, how would you comment on your combined roles of creator and spectator?

Alvaro Urbano: The work “My Boy, with Such Boots we may Hope to Travel Far” is based on a cryptogram that appears in the book "A Journey to the Center of the Earth" by Jules Verne. The first part of this long project was made as a permanent installation where sculptures (in the shape of runes from this cryptogram) were scattered throughout a 4 kilometers hiking path in South Tyrol, in the Italian Alps. In this case, the work isn't conceived for a single spectator but nevertheless, I believe that there exists a particular tension and a higher degree of intimacy when there is only a single spectator confronting a piece. This tension and the level of intimacy changes when the pieces are placed in nature or in unknown, uncanny, heterothopic, or non-familiar places. For instance: when you walk in the mountains your senses change - the way you breathe, the way you walk, and the way you experience and unfold the space around you. This type of corporeal awareness will hopefully appear as well in "I", at the very top of Mole Antonelliana, where only a few people have had the chance to go.

For me, it is not crucial if someone discovers or not the entire cryptogram. I guess it is more about the journey itself: changing the landscape by inserting my work and opening small tangible doors to Verne’s fiction, and imagining perhaps that there exist more letters from the cryptogram in some other part of the globe. In my work, I see the audience as having the ability to walk in-between the lines of a narration: where they have the space to become characters of a work of fiction, almost without noticing.

In response to your question on the role of creator and spectator, I can tell you about my permanent piece Osservatorio (2014), placed in the garden of Villa Romana in Florence. The work is a sort of hermetic, half-buried capsule with a big skylight, so designed to sleep under the stars at night. This piece is like Mole Antonelliana’s "I": it is conceived for one spectator or user. I remember I slept there for almost a month and every night was different, and the dreams, the light, and the weather conditions all played a strong role in the experience of the piece. This also happens in my Berlin studio-home, where my partner and I tend to live surrounded by our own works, and they become camouflaged within our daily life, almost as if they were pieces of furniture. I would affirm, then, that I am more of a creator-user rather than a creator-spectator.

MM: The Mole Antonelliana is a landmark building in the city of Turin, and holds the title for tallest museum in the world (the National Museum of Cinema). What are the challenges of organizing a show in such a space?

Ramona Ponzini: Organizational challenges are not new for us: our first show was meant to be experienced by a group of birds, and this meant that we had to follow a series of regulations to ensure the safeguard of the feathered; for our second show, we built a river of poisoned water inside an art depository - so that was also kind of a dangerous operation!

For this project, we chose to utilize the symbol of our city - Alessandro Antonelli’s “vertical dream”, but we decided to set up the show in its spire - the tallest and least accessible part. This area of the building is usually off-limits for the public. I have to say that the enthusiastic response for this crazy show by Alberto Barbera, the museum’s director, and from all the staff of the museum, has been fundamental to its development. They were most willing to accommodate this project, and were especially cooperative with regards to figuring out all the security issues, which is a paramount element in this type of project.

Another critical factor was the elaboration of the participant selection process, and the management of those people who booked a spot for the event. We needed to identify forty people, from which only one was allowed to climb to the top and see the whole show. The event on the 5th of November took place simultaneously in two different settings: atop the spire, for just one lucky person, and on the ground floor of the Mole, where the remaining thirty-nine participated in a sort of ritual to gain favor with the ascent of the sole spectator (the person who found the golden ticket with their chocolate bar).

Last but not least, there’s the chocolate itself: during his first visit to the Mole, Alvaro was really impressed by the panoramic elevator, which immediately reminded him Roald Dahl’s novel “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory”. Torino is also famous for its historic chocolate factories, and we decided to ask A.Giordano, one of the very best chocolate manufacturers around, to act as technical sponsor for this project.

This ritual/show/event was a very complex mechanism, and all of these elements needed to weave together just fine in order to work.

MM: Treti Galaxie has a particular focus towards the relationship between contemporary art and its audience. In your shows, there is the feeling that the audience has a role to play for the benefit of art, and you go to great lengths to engage the audience in their role through theatrics. Why are you interested in creating this dynamic?

Matteo Mottin: I think that, in a real life show, you have the rare opportunity to directly address the unconscious mind of the viewer. Of course, you can choose to write out a beautiful text that tells you everything about the show and you can give it to the people who come to see, hoping that they will read it carefully - but maybe a spectator deserves more than that.

With Treti, we want to build timeframes that serve to enhance the viewer's perception towards the art-and-research-works of artists whom we love. Being surrounded by birds while walking on top of a huge canvas-terrain, or being separated from the artworks by a river of poisoned water, or having to climb the city's highest building in order to recollect scattered pieces of a far-reaching project: all these occurrences provide the viewer with something that reading texts and seeing pictures cannot.

Because our rational memory tends to fade away, the shows that we see in person will, in some years, look exactly like their installation views: which are always framed from the point of view of a single person - the photographer. Experiences, on the other hand, tend to linger in our memories, because an experience is not something that has been given to you – it’s whatever you’ve decided to take away.