Illustrator Jim Kay on Bringing the World of Harry Potter to Life

Fans of the series will be familiar with the illustrated Harry Potter books. Jim Kay is the man behind the images and ArtDependence had the opportunity to catch up with him to find out more about how he brought the series to life in visual images.

In 1997, a little-publicised book by an unknown author hit the bookshelves: Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. Within months, the entire publishing industry had been shaken by the unprecedented success of J.K Rowling’s debut children’s book. Having been turned away by several publishing houses, Rowling has gone on to become a household name and one of the most lucrative authors of our era.

Fans of the series will be familiar with the illustrated Harry Potter books. Jim Kay is the man behind the images and ArtDependence had the opportunity to catch up with him to find out more about how he brought the series to life in visual images.

ArtDependence Magazine (AD): Do you think book illustration is undervalued as an art?

Jim Kay (JK): That's a tricky one. I think there is a great deal of affection for illustrated children's books, both here and overseas. The fact that the same books keep selling, such as Eric Carle's Very Hungry Caterpillar, seems to be in some degree due to the strong bond adults feel to visual stories from their own childhood. It may also be because we are prone to take fewer risks on new and untried stories when purchasing books for younger readers. I do think, however, illustrated books for young adults, and in particular graphic novels and comics, are undervalued in the UK. From my experience people dismiss graphic novels as rather niche, or limited in their scope, or take the view that they are meant for people who don't want to read 'proper books'. This frustrates me because graphic novels have been progressive both in the visual techniques used to convey a story, and in subject matter that has perhaps been taboo or slower to reach non-illustrated printed medium for young adults.

There has been a gradual shift towards critical respectability, partly perhaps through the success of screen adaptations, and also in the growing number of women who write and/or illustrate graphic novels, particularly for independent publishers. Librarians too in the UK have been instrumental in legitimising the strength of storytelling through the illustrated medium, and illustrated books are a wonderful tool in aiding reluctant young readers to get into the habit of reading.

I like the fact that there is a blurring of the lines now, that some children's books place a foot in the graphic novel's camp; the onus being on conveying the message through the most immediate and effective means possible. San Tan is an expert at this, Pam Smy's book Thornhill is a wonderful hybrid of diary and comic strip, and Emily Carroll's Through the Woods is a visual feast of storytelling. With regards to what might be described as 'traditional' high production children's books; hardback volumes with high production values in terms of binding, paper stock, quality of typography and illustrations, have also seen a growth in success.

Templar Books arguably reinvigorated the sales of tactile, beautiful volumes with their 'ology' series of nostalgic fact books a few years ago. There's still a way to go with regards to illustrated books for adults. The Folio Society produces exquisite books, such as 'Foucault's Pendulum' illustrated by Neil Packer. Brecht Evens, a favourite of mine, writes and illustrates astonishing, lurid, graphic novels on provocative and adult themes – take a look at his book Panther. His books are a hallucinogenic visual blend resembling stained glass and neon nightclubs. Sadly, most of these books are difficult to find and seldom sit on the shelves of high street bookstores in the UK.

Flourish & Blotts © Jim Kay

Hagrid © Jim Kay

AD: What is your process when creating a character for a book?

JK: I can only speak from my own point of view, but I populate the books in the way a casting team might populate the characters of a film. I read the text, again and again, and let the visual character coalesce roughly in my mind, then look around me at different people and see who would fit. I usually take bits of different people, and stick them together. While designing Hagrid I looked at the eyes of different alcoholics, both locally and through history. I was fascinated with Luke Kelly's face, from The Dubliners, but eventually settled on the eyes of Winston Churchill, and the nose of somebody I saw in my local town. I've yet to illustrate a story I have written, and so I'm always trying to guess what the author was after. It's a sticky problem, because in cementing a character visually on paper, you are regrettably going to deprive a reader somewhere of their own mental interpretation of the text (this is why I left the character Conor in A Monster Calls as a silhouette). For Potter it's been different because the children will age over the series, and so I've had to literally 'cast' the book, using real people to help inform the way children turn into young adults.

AD: You illustrated the Harry Potter books. How did that come about?

JK: From my point of view, out of the blue! I'd only really just started in children's books, and I'm still not sure why I was chosen. I hadn't really drawn children before, or anything particularly colourful. My agent called and offered me the whole series. I agonised over it (I still do), because I was so fond of the film franchise, but in the back of my head my old lecturer's voice would say 'if something frightens you, it's probably worth doing'. Illustrating Potter terrified me, but every now and again in my life I've done something which seems irrational, or way out of my depth, and ultimately it's turned out ok. I still don't feel like an illustrator, I don't know if I ever will. It has been extremely difficult, it's not a commission that particularly suits me in many ways, but I'm so glad I took it on, and so grateful I even got the chance. I'm hoping that there will be a long line of illustrators providing their own interpretations of Potter, in the same way that Alice in Wonderland has inspired illustrators over a century.

AD: What upcoming projects are you working on?

JK: Because Potter is a very, very difficult commission for me, it's literally all I have time for. If I work seven days a week, every hour of the day, it's still a struggle to get the book done in time. I'm not a natural illustrator, I produce a vast amount of rubbish before I get to an image that actually works. I find sitting on my own all day extremely unnatural. I'm not alone, by the way, I think a lot of readers imagine illustrating books to be an idyllic relaxing career, but a good deal of us find it very frustrating, hard work. Don't get me wrong, it's a privilege to be able to do it, and it is a career so dearly bought for many of us, at the expense of friends, free time and so on, but gosh I find it difficult. So my upcoming projects are: Potter, books 4-7, that's all I'll have time for. But what an amazing way to spend my time!

Harry Potter in cupboard © Jim Kay

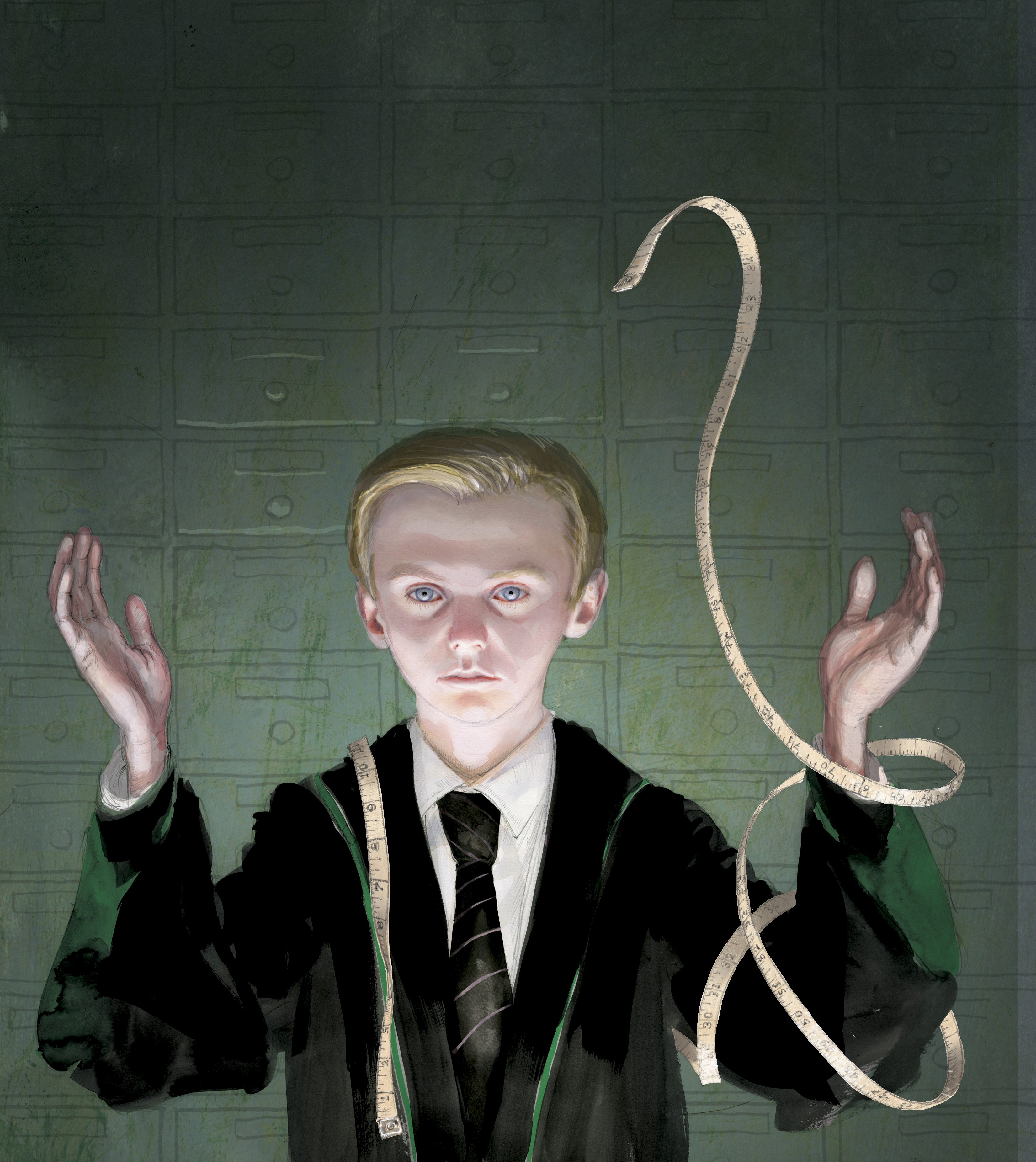

Draco © Jim Kay

AD: What is your ultimate dream project?

JK: I actually like to change career every few years. I'd love to make hats. My partner is a milliner, and we have both had classes from two wonderful experts in the field recently. There is such pleasure in working in three dimensions, and hats are limited only by the fact that the finished piece has to fit on someone's head. It can literally be anything. It's great fun. What I admire about milliners is that their craft is honed over many years, to the point where their stitching becomes invisible, and hours of labour goes into parts of the hat that the owner would never even see. It's their discipline and craft I really admire, and the paraphernalia that accompanies the profession; the hat blocks, the silks, the feathers.

I am also very fond of gardening. I suffer from bipolar disorder, which makes most of my daily life a living hell, but oddly when I garden it's the only time I can think positively about the future. You are creating a living visual picture that comes into fruition a year or maybe longer from now. Everything else in my life is a battle to just get through the day. It's almost impossible to plan ahead - except when I look at the garden. I only get a few minutes a day out there, but without it I'd be lost.

AD: Your website is called Creepyscrawlers. Where does the name come from?

JK: Almost everything I grow in the garden is designed to be the food plant of one insect or another. I'm fascinated by insects, always have been, so creepy scrawlers came as a pun, a mixture of my two interests; entomology and scribbling. I think I called one of the shops I illustrated in Diagon Alley Creepy Scrawlers. Almost every shop that I invented on Diagon Alley has some personal connection.