"I try to create a place of disorientation" - interview with Kehinde Wiley

In anticipation of the upcoming exhibition Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic at the Brooklyn Museum, Artdependence Magazine reached out to the artist with several questions about his work, his models, and the hidden meanings behind his paintings.

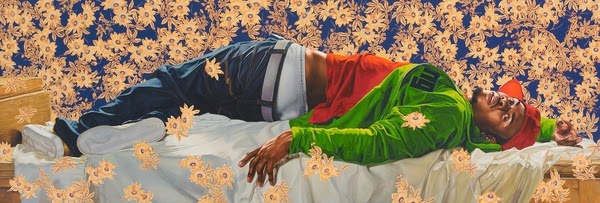

Muscular black and brown bodies wearing sporty clothes posing on a bright floral background - this is just what you see at first glance when looking at Kehinde Wiley’s paintings. Kehinde Wiley (born 1977) is a New-York based painter who gained recognition for his naturalistic portraits and recognizably colorful style.

His referral to the Old Masters is deliberate and consistent. Heroic poses, facial expressions, even the background patterns - all these attributes inevitably force us to think of the Old European School of Painting. But then, the black or brown skinned model, usually male (but from 2012 also female) enters into conflict with our expectations, highlighting prejudices and disturbing the conventional. This is what Kehinde Wiley wants from us and leads us towards: to experience the contradiction between the model and the background, between Old Masters and contemporary art, and finally, between black and white. But in the end you begin to see all these as one perfectly realized concept, all contesting components fitting perfectly and seamlessly in one piece, bearing of tales of the past. At the same time, his oeuvre is as contemporary as can be possible, raising questions of gender, race and politics.

In anticipation of the upcoming exhibition Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic at the Brooklyn Museum, Artdependence Magazine reached out to the artist with several questions about his work, his models, and the hidden meanings behind his paintings.

Artdependence Magazine: In one of your previous interviews you explained that one of the reasons you refer to the Old Masters’ paintings is because you like to fantasize about replacing the European ceremonious aristocrats depicted in those classical European paintings with your contemporary fellows, casually dressed in baggy jeans, T-shirts and sportswear. Is there a political or racial context behind this?

Kehinde Wiley: There is a political and racial context behind everything that I do. Not always because I design it that way, or because I want it that way, but rather because it’s just the way people look at the work of an African-American artist in this country. If I were making paintings of a bowl of fruit it would still be viewed through some sort of political lens, because the viewer wants to create a type of narrative around the political theme when they look at work depicting black and brown models.

Kehinde Wiley (American, b. 1977). Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps, 2005. Oil on canvas, 108 x 108 in. (274.3 x 274.3 cm). Collection of Suzi and Andrew B. Cohen. © Kehinde Wiley. (Photo: Sarah DiSantis, Brooklyn Museum)

AD: Your characters are usually torn away from reality and placed in some completely made up context. What do you want to achieve by this?

KW: Generally I try to create a place of disorientation, as a way to upset the natural balance that the viewer may have when they look at one of my images. What I love in art is that it takes known combinations and reorders them in a way that sheds light on something that they have never seen before or allows to consider the world in a slightly different way.

|

| Kehinde Wiley (American, b. 1977). Saint Remi, 2014. Stained glass, 96 x 43 1/2 in. (243.8 x 110.5 cm). Courtesy of Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris. © Kehinde Wiley |

AD: The pattern of the background is always fantastic. Who works on it?

KW: Well, my assistants generally do all the flowers and all of the decorative work. I concentrate on the figure. The backgrounds by design are a very key part of the conversation, because I want a kind of fight or pressure to exist between the figure and the background. Unlike the background in many of the paintings that I was inspired by or paintings that I borrowed poses from - the great European paintings of the past - the background in my work does not play a passive role. On the contrary, my desire is that the viewer sees the background coming forward in the lower portion of the canvas, fighting for space, demanding presence. Almost as though the painting itself becomes the embodiment of a type of struggle for visibility, and this might be considered the main subject of the painting.

AD: Is your “World Stage” project still ongoing? And if yes, what will be your next country in the series?

KW: Well, it's a secret, it will definitely end at some later stage, but for now I’ll keep it as a secret.

AD: Do you think that at some point you will make an exception for a white person to be your model?

KW: I have been painting white people for much longer in my life than I have done for colored people. I studied shades, textures by painting after the Old Masters, the classical European paintings, as part of my educational process. I have been painting models with black and brown skin only for the past years. So, I did already have this experience, this is how I have come to the paintings I do now.

AD: Have you ever done a self-portrait?

KW: In some way they are all self-portraits, but I think I know what you mean by asking this – I would say, it is too idealistic to paint yourself.

AD: Thank you, Mr. Wiley, good luck with the exhibition!

Kehinde Wiley (American, b. 1977). Femme piquée par un serpent, 2008. Oil on canvas, 102 x 300 in. (259.1 x 762 cm). Courtesy of Sean Kelly, New York. © Kehinde Wiley

***

The works presented in Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic (February 20–May 24, 2015) raise questions about race, gender, and the politics of representation by portraying contemporary African American men and women using the conventions of traditional European portraiture. The exhibition includes an overview of the artist’s prolific fourteen-year career and features sixty paintings and sculptures.

|

| Kehinde Wiley (American, b. 1977). Houdon Paul-Louis, 2011. Bronze with polished stone base, 34 x 26 x 19 in. (86.4 x 66 x 48.3 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Frank L. Babbott Fund and A. Augustus Healy Fund, 2012.51. © Kehinde Wiley. (Photo: Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum) |

Through the process of "street casting," Wiley invites individuals, often strangers he encounters on the street, to sit for portraits. In this collaborative process, the model chooses a reproduction of a painting from a book and reenacts the pose of the painting’s figure. By inviting the subjects to select a work of art, Wiley gives them a measure of control over the way they're portrayed.

The exhibition includes a selection of Wiley's World Stage paintings, begun in 2006, in which he takes his street casting process to other countries, widening the scope of his collaboration, sculptures and stained glass paintings. Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic is organized by Eugenie Tsai, John and Barbara Vogelstein Curator of Contemporary Art, Brooklyn Museum. A fully illustrated catalogue published by the Brooklyn Museum and DelMonico Books • Prestel accompanies the exhibition. More information about the exhibition is here.

Kehinde Wiley (American, b. 1977). Shantavia Beale II, 2012. Oil on canvas, 60 x 48 in. (152.4 x 121.9 cm). Collection of Ana and Lenny Gravier, courtesy Sean Kelly, New York. © Kehinde Wiley. (Photo: Jason Wyche)

Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic is organized by Eugenie Tsai, John and Barbara Vogelstein Curator of Contemporary Art, Brooklyn Museum. A fully illustrated catalogue published by the Brooklyn Museum and DelMonico Books • Prestel accompanies the exhibition. More information about the exhibition is here.

Kehinde Wiley's site is here.