“I like to explore the ways in which to perform disagreement” – an interview with Marco Godoy

Marco Godoy (Madrid 1986) understands his artistic practice as a way to find spaces from which to redefine social and political events. His works are linked to protest and political art, but the aesthetics and mediums he uses present new approaches from which to address specific topics.

Marco Godoy (Madrid 1986) understands his artistic practice as a way to find spaces from which to redefine social and political events. His works are linked to protest and political art, but the aesthetics and mediums he uses present new approaches from which to address specific topics. The Spanish artist based in London has exhibited in Matadero Madrid, The Dallas Museum of Contemporary Art, Stedelijk Museum s-Hertogenbosch, Liverpool Biennial 2014 and the Institute of Contemporary arts (ICA), among other centres. Artdependence Magazine interviews Marco Godoy in London, where he has been selected to exhibit at Whitechapel Gallery’s The London Open 2015, which will be on show until the 6th September.

ARTDEPENDENCE MAGAZINE: When did you decide to become an artist? What was your first impulse to study Fine Arts?

MARCO GODOY: I was actually not planning to study Fine Arts, but Architecture. I was also interested in Design, because it has a more practical and functional application and it implies more contact with people. I decided to study Fine Arts and specialise in Design as in Spain there was not a specific university degree for it. In the end, I didn’t do this specialisation, because I realised that through art I could talk about things that concerned me. That’s when I became interested in video, photography and in working with people.

Marco Godoy, This is no time for metaphors, 2012

AD: You studied Fine Arts and have recently completed an MA in Photography at the Royal College of Arts (London). Despite this, in your practice you use several different mediums: sculpture, video, photography, performance. Is there any format that you feel more comfortable working with?

MG: It depends on the topic and the possibilities of production I may have at the time.

I did my BA at the Complutense University in Madrid, which has a very traditional and academic methodology. In the last years of university, I joined the collective “Todo por la Praxis” to work in projects related to architecture, urbanism and activism, and looking for intermediate spaces between those topics. I did my last year in Chicago, where I focused on photography and video. Then I went back to Madrid and thought about doing a Masters.

The masters of the Royal College are divided by discipline departments, but this doesn’t necessary mean that you can use only one medium. In the two years of MA I barely took a photograph. The students at the painting department do performance, the performance ones do painting, the sculpture ones do sound…You start doing one thing and finish doing another. This is positive.

When I started, Peter Kennard was teaching there. During many years, especially during Thatcher ages, he was working with newspaper and he understood the distribution mediums as part of his job. He studied how to develop a work about a topic related to the present and how to distribute it in a coherent way. He worked a lot with newspapers, neighbours associations, with activists and in protest actions. The work of Peter Kennard was a key fact for me to study the MA in Photography.

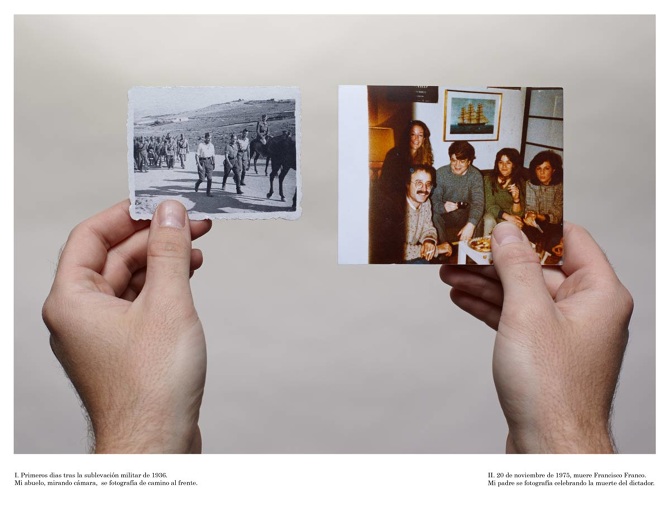

Marco Godoy, What we still have to talk about, 2013. Family Portraits.

AD: On the occasion of the 2014 edition of Bloomberg New Contemporaries at ICA you stated: “I understand my work as the search for ways in which to perform disagreement. My intention is to use the exhibition space as a platform for actions and activities that link with specific social and political events in both the past and present. My practice acts as a response to these performances”. This reminds me to your project ‘This is no time for metaphors’, in which the art operates somehow as a means of social response.

MG: When I was already living in London, the Council of Girona (Spain) decided to install locks in the supermarkets' garbage containers as a cosmetic measure to avoid people looking for food there.

There’s a difference between Spain, a country where the economic crisis has a bigger impact, and London, a sort of bubble where, apparently, there are not that many problems. I arrived here and I thought that all these abstract metaphors we work with doesn’t make sense. I think that works have to refer to specific topics.

What the Council of Girona did, was partly a consequence of the cuts, but it was also due to an institutional attitude that doesn’t understand the situation. There was a need for other images besides the ones that are published on the newspapers. It was an opportunity to bring that situation to other places, like London, to allow other people to understand what was happening in Spain.

So, my intention with this work, as with many others, was providing images to something in particular, to see how we can give it visibility and talk about it from an alternative perspective.

Marco Godoy, What we still have to talk about, 2013. Cast from the wall in Sant Felip Neri Square. Resin. 2x3 meters. 2013

AD: This is related with what you mentioned before about your interest in images and how the images somehow create new realities.

MG: Yes. When I say “the search for ways in which to perform disagreement” I mean that the images are important because there’s always an official channel. Through media and social media channels we create events and we are able to redefine them with images. We can identify the stories that are overlooked and try to get them back in another format.

This is related to my piece “What we still have to talk about”, regarding those images that have been left pending.

Marco Godoy, Claiming the Echo, 2012, HD 16:9, 5:25min

AD: Actually, this piece is currently on show at the London Open 2015 at Whitechapel Gallery. This is a project that brings together topics of historical consciousness about the Spanish Civil War and topics related to your own family.

MG: Regarding the topic of the historical consciousness there are many things that are being discussed nowadays. The Civil War has been told in a specific way, with a specific intention and this means that there has been a strong exercise of power. I’m interested in how the history is created and controlled by power circles.

Our generation has grown in democracy, detached from the war, the dictatorship and the transition to democracy. Because of this distance we have now the chance to bring into light things and redefine them, like the fact that Spain is the second country with the highest number of common graves (many of them still unopened).

I don’t usually like to include personal topics in my projects, but in this case, I considered that the history of my family was quite common.

My grandfather was a soldier and a convinced Falangist [a member of Spain’s fascist ideology party created in 1933]. He had a picture of himself going to the front at the beginning of the war. Looking at family albums I found this picture and one of my father, who belonged to the Joven Guardia Roja [a communist youth organisation], celebrating Franco’s death [the dictator died in 1975 after almost forty years of regime].

I like how those two pictures that had joined together in the family album represented a hinge and I think that my generation could be a third step in this process.

So, this project has two parts, the photos and the cast of the wall. This wall, which is in Sant Felip Neri Square, is one of the few visible evidences of the war that still remain in Barcelona. I thought it could be a monument that is important to highlight to give it a new definition from the original one.

What historical documents remain? There are not many traces of the war represented by gunshots and wounds.

Marco Godoy, El sistema. The system. 2014.Video HD, 2' 30''

AD: There are more remains from Franco’s years…

MG: That’s right. What documents do we have besides the ones created by the winners? And what neutral spaces do we have to redefine these topics? I believe that it’s important to distance yourself from something in order to get closer to it.

This is something that I tried with the project ‘Claiming the Echo’. I tried to work with images to break away from the foreseeable ideology. If I work with protest aesthetics, it is likely that this aesthetic belongs to a certain ideology. In this project in particular, the images were linked to the people fighting against the economic cuts, which are normally associated to a left-wing ideology

AD: Regarding ‘Claiming the Echo’, was your intention to bring into light the topics discussed in the protests by using a choir as a way to separate it from its original context?

MG: Between 2010 and 2011, at the crisis peak, there were around 2,500 demonstrations per year in Madrid. After the 15M movement [Spanish anti-austerity movement that in 2011 organised a series of protest camps occupations] there was a new way of protest and to talk about ideology, different from the classical left-wing, traditionally associated to syndicates and workers movement. A new language materialised, more neutral and detached from this tradition.

I felt there was something really powerful in how people chanted demonstration slogans. “Social peace is going to end” was a threat, one of the old slogans, but it suddenly had a renewed validity. So, I asked myself “how can we chant this slogan to someone who might disagree with our protest and might never participate in a demonstration?”

At that time I was digitalising the archive of the 15M movement, so I was familiarised with the slogans. I met the choir Solfónica, which was created in the camps at Sol [square in Madrid] and they have a repertoire to support protests.

Marco Godoy, Gallery of Monarchs, 2014. Leopold I of Belgium.

Voice implies some rituality, but it’s also something physical. When we are in a demonstration we become stronger and empowered. I talked to Solfónica about ways of collaboration and jointly with the director and the sound artists Alicia Hierro, we decided to adapt the slogans to a baroque piece by Henry Purcell. “It's called a Democracy but it's not a Democracy” and “Social peace is going to end” became odes for the King by Purcell with a change of lyrics. It was all about having some distance from the original context and finding a visual format to tell the story, so we took the Solfónica to an auditorium to sing the slogans.

This is a project that works in two different ways. On the one hand, it was an opportunity to bring the Solfónica in an exhibition space, usually not linked to social movements. It is a way to be able to talk to someone that might have a complete different ideology. On the other hand, the choir included the songs in their repertoire and they now sing them in demonstrations. It is very powerful to hear the choir singing “We are not scared”.

Devaluing an image consisted in the slow, manual erasing of euro coins using sandpaper. Injuve Award 2012.

AD: Last year you were selected as an artist in residence in Kiosko Galería (Santa Cruz, Bolivia) thanks to Gasworks and the Triangle network International Fellowships. Tell us more about this experience.

MG: When they invited me they didn’t really expect me to have a planned work. You arrive there and it’s a place with complete different codes. It took me a while to see what could I do there that made sense in that context. Besides this, as a Spanish there…well, there are also some things that we still have to talk about.

Bolivia is experiencing a beautiful moment, it’s one of the economies that is growing the most in Latin America and people have the feeling that the country belongs to them.

And Kiosko is one of the reference contemporary art centres in Bolivia. It is a small space, with a very open programme. Every five years they organise the international gathering Abubuya where they take curators and an artists to live in a boat in the rainforest for fifteen days.

AD: So, it was there where you created your work ‘The System’.

MG: Yes. This is a video that uses a text by Eduardo Galeano, which talks about a progress that is destructive, that devastates everything, but can’t avoid disagreement. For me, Bolivia is developing an aggressive progress, a bit destructive, so I wondered what sense did it make for me to be there in the Amazonia, a place that will unavoidably disappear.

The best part of Abubuya was that all of us spent many days thinking about this. Our work makes sense in the city, but what do you have to say when you are in the jungle? At the beginning we had a general crisis, but at the end we all produced works and we organised an exhibition. We have developed collaborations out of the experience. For example I keep collaborating with Daniel de Paula, from Brazil, and Kate Levant, from the United States.

Marco Godoy, [Son of a Priest. Recovered Phrase]. 2014.

AD: Your work reflects the social reality in Spain in the context of the economic and political crisis. Regarding art, how would you define Spain’s artistic scene nowadays, considering that you have lived and exhibited your works in other countries?

MG: I think there’s a great bunch of people doing interesting things in Spain. There are really good institutions, although the public ones have less budget.

But still, I think we are lucky and that we have the opportunity to see things that are not that usual. There are good programmes and institution, such as big ones as [Museo Nacional Centro de Arte] Reina Sofía and MACBA, centres like Matadero [Madrid], La Panera, La Capella and La Casa Encendida. And there are a lot of independent artist-run spaces.

The crisis has affected the Arts, as many other spheres.

AD: Last 1st August you participated in the performance “songs for someone who isn’t there” curated by Sarah Hardie and presented in the frame of the Edinburgh Art Festival. In this Project you also refer to British politics.

MG: This is a curated project where voice, memory and nostalgia about the past play an important role. Sarah and I worked on iconic quotes from Thatcher’s era to give it another approach. We also considered the architecture of the place where the performance took place, a 19th century college at the University of Edinburgh.

AD: Are there any future projects that you are able to share with us?

MG: I don’t really like to talk about unfinished projects. At the moment I know that I will work with small formats because I depend on the production and most of the ideas I have are expensive.

There are recurrent topics in my work. I’m especially interested in how the power is performed and constructed, and how power relationships are not only represented in classical or authoritarian systems, but in institutional relationships, in a neighbour community, within a group of friends or a couple.

I like to analyse the role of the images in the construction of power. An iconic example could be monarchy, which condense a kind of relation between the monarch and the citizens. It is a legacy that remains thanks to its protocol, quite baroque and adorned, and designed to legitimate the monarchic power, which otherwise, would lose its sense.

I’m very interested in the idea that power, unless authoritarian, becomes fiction. I like to explore the ways in which to perform disagreement, to demonstrate that we disagree from these forms of power that tend to be symbolic.