“I am interested in the overall physical experience of the viewer – not just a visual experience.” ArtDependence Speaks to Karl Haendel

ArtDependence caught up with Karl Haendel to find out more about his work, his methods and his next projects.

Born in New York in 1976, Karl Haendel currently lives and works in Los Angeles. He is known for creating meticulous, photorealistic pencil drawings, most of which are based on appropriated photographs. Haendel often works on a large scale, removing the images from their original context and playing with our relationship to familiar images, signs and signifiers.

Haendel’s work is in public collections in the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, The Museum of Modern Art, New York and the Guggenheim Museum, New York.

His drawings have also been included in the Whitney Biennial 2014 and the 12th Biennale de Lyon in 2013.

ArtDependence caught up with Karl Haendel to find out more about his work, his methods and his next projects.

ArtDependence Magazine: You studied Art Semiotics, can you explain a little about that course and how it is reflected in your art?

Karl Haendel: Semiotics is the study of sign systems–how signs and symbols are used. In this case signs refer to language and images, not street signs, which can be confusing (my father thought I was studying traffic). So I suppose it's the study of how meanings are generated. It included Marxist, Post-Structuralist, and Post-Colonial theory - Derrida and Foucault, that kind of stuff. I don’t have the patience or the wherewithal to continue reading such heavy theory, but the concept of addressing how we as a culture make meaning continue to be helpful for me.

AD: Your drawings are on a very large scale. Do you think there is a difference in the viewer’s emotional relationship with the work compared to small scale or more intimate drawings?

KH: Although I often make drawings, the historical work that has most influenced me is Minimalism and Post-Minimalism – the way this work took into account the viewer’s body and position in space. I’m interested in the overall physical experience of the viewer – not just a visual experience, so I don’t treat my drawings as little windows into imaginary spaces – they are shapes on walls or floors in spaces occupied by other shapes and viewers. They are relational in nature. These days, the purity of separating yourself into a ‘kind’ of artist is not that interesting to me, so I make drawings but I deal with space and how the viewer can be physically acted upon by the objects in that space. This can only be accomplished with a variation in size, from the small to the larger than life.

AD: Your drawings are often presented in a form that is different from the standard size and structure of drawings. It can be quite an overwhelming experience to look at them. Are you not afraid this distracts the viewer’s eye from the essence?

KH: Well, I guess that depends on what you assume the essence to be. If the essence is fine pencil work and detail, then yes, the all over the place installation distracts. But I am specifically interested in that tension, between the viewer’s physical awareness of her surrounding, and her optical interest in fine touch and detail. Can the two exist together? Or does the overall experience deny or repress the inherent labor in the drawing? If it does, what does that say about the value we as a culture place on labor now that we are in the age of Instagram and constant spectacle?

AD: You often draw politicians. Is a drawing of a politician enough to make it political art?

KH: No. I don’t name it political art. Are we talking about political art as a type of work that attempts to induce change or action? As much as I like that kind of work, I don’t think art is very good at making change. I do a fair amount of political organizing and action, but I do that on the side and do not call it art. In my work I might draw politicians, because who we elect (or overthrow or don’t overthrow) tells us who we are as a people. It reflects our values and beliefs. Political identification, like racial, sexual or class identification, is important to explore.

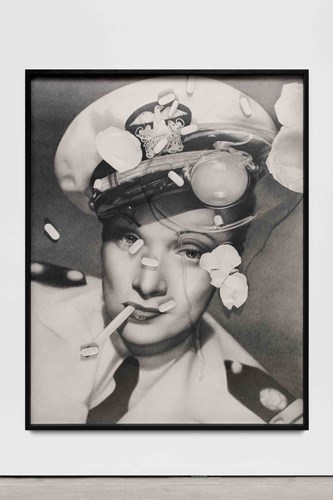

Karl Haendel, "Marlene Dietrich (with cracked egg and Zoloft)", 2017. 166 x 130 cm. pencil on paper. Courtesy of WENTRUP, Berlin. Photo: Trevor Good

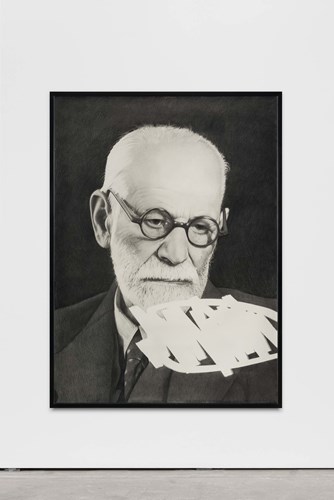

Karl Haendel, "Sigmund Silent 2", 2017. 157 x 115 cm. pencil on paper. Courtesy of WENTRUP, Berlin. Photo: Trevor Good

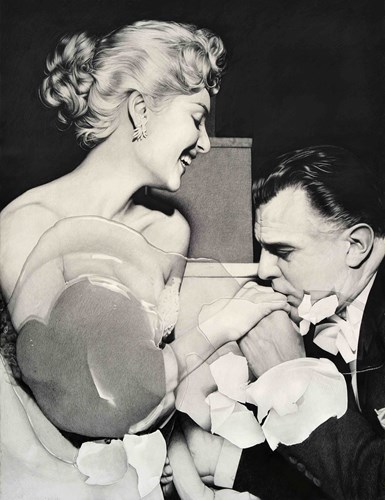

Karl Haendel, "Antiquated Gender Dynamic (with cracked egg)", 2017. 170.18 x 130.81 cm / 67 x 51 1/2 in. pencil on paper. Courtesy of WENTRUP, Berlin. Photo: Trevor Good

AD: Your work Arabic Spring 1 deals with the refugee crisis, the composition of this work reminds me of the Marine Corps War Memorial and Liberty Leading the People by Delacroix. What makes these 3 works so strong in your opinion?

KH: Historic painting was the highest form of art in the French academic tradition, as apposed to landscape or genre painting. And I hold that to be true - not the painting part, but the part about history, artwork that seeks to define and mark for the future our current historical time. It need not be painting, and currently, it rarely is. William Kentridge’s films or Jason Rhoades’ installations – to me, these are in the spirit of great history paintings. Like Delacroix, these artists define and make us take note of a particular historical and cultural moment where things are in flux. I am not attempting to define the experience of those who are currently living through change and crisis in the Middle East – I cannot know that perspective. The Arab Spring drawings are about us here in the West, and how we handle, or fail to handle, immigration and migration. It is a test of our beliefs in human rights and dignity, and we seem to be failing the test. I think when we look back in a century at our current moment, we will be ashamed of the way we failed immigrants and denied them their human rights.

AD: What are your future plans? What series are you working on as we speak?

KH: Right now I am working on a new video about a man who gave everything away, as well as a proposal for artwork in a new train station in Los Angeles. But for my next show, in Berlin, which will be at Wentrup in the fall of 2018, I have the idea to do a doppelganger show. Each drawing will have a "twin" - sort of the same drawing but just slightly different in some way (composition, perspective, tonality, orientation, etc.). The space will be divided in half by a wall, and the two shows will be mirror images of each other - but the image in the mirror won't be exact. I am hoping this difference will produce a psychological discomfort and a sense of the uncanny. Viewers will have to walk back and forth between the two halves to compare and contrast the drawings, to see what is different in each drawing. Viewers will be very activated in the space, but they will also have to look closely.