Hungary’s Nazi-Era Art Thief fled to Brazil

In 1944, Hungary’s cultural institutions became active participants in the Holocaust—not merely by omission but by order.

As Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz, Hungarian museums, universities, and ministries mobilized to confiscate their belongings: paintings, libraries, Torah scrolls, antiques, and sculptures. This was not incidental plunder but bureaucratically orchestrated cultural theft—with one man at the center: Dénes Csánky.

Born in Budapest in 1885, Dénes Csánky was an art historian and senior official within Hungary’s Ministry of Religion and Education. During the Holocaust, he served as the head of the Ministry’s Museum Department, coordinating the systematic seizure, inventory, and redistribution of thousands of Jewish-owned artworks and cultural artifacts. He appears repeatedly throughout the Hungarian archival microfilm reels 143, 144, and 145, preserved by the Zekelman Holocaust Center and World Jewish Restitution Organization, identified as overseeing the large-scale looting operations targeting Jewish families such as the Hatvanys, Herzogs, and others.

Verified Archival Cases of Csánsky Leadership in Looting:

Baron Ferenc Hatvany’s Collection (Reel 145, Slide 351)

A 1944 archival document confirms that crates of Baron Ferenc Hatvany’s artworks—confiscated under Hungary’s anti-Jewish measures—were received by government officials under Csánky’s direct oversight for “safekeeping”.

Systematic State Inventories (Reel 145, Slides 393–395, 420–429)

Documents meticulously inventory looted artworks, including pieces by Cranach, Courbet, Utrillo, Van Goyen, and Mihály Munkácsy, many transferred directly into Hungarian National Museum and Szépművészeti Múzeum holdings. These inventories were not random acquisitions but deliberate confiscations orchestrated through Csánky’s official position.

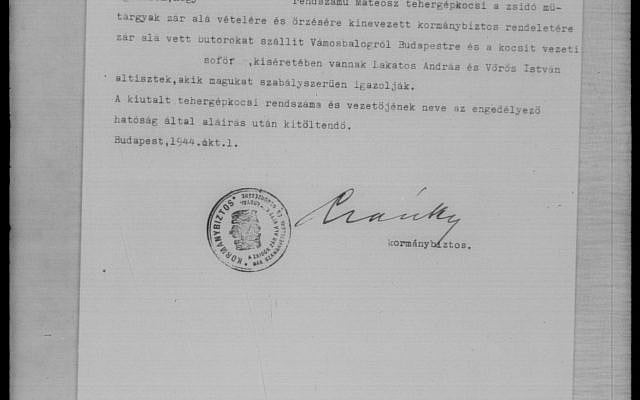

Institutional Complicity (Reel 143, Slide 4, 66–70)

A key document lists over 20 Hungarian institutions designated to receive Jewish property, from the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest to regional museums nationwide. Csánky’s signature and seals appear repeatedly, authorizing cataloging, redistribution, and institutional absorption of stolen Jewish cultural assets.

In short, Csánky did not merely facilitate cultural plunder—he led it.

Career Undisturbed by Holocaust Crimes:

While Hungary’s Jewish community was decimated, Csánky’s professional career continued uninterrupted. Amid rising postwar scrutiny, he quietly fled Hungary in 1949, settling comfortably in São Paulo, Brazil, where he lived freely until his death in 1972. He was never investigated nor held accountable for his role in Hungary’s Holocaust-era looting, effectively escaping justice—just as many looted artworks disappeared into museum basements or private hands.

The Injustice Continues Today:

Shockingly, Dénes Csánky is currently listed as a featured artist in the Hungarian National Gallery and other state-affiliated institutions. His animal sketches and watercolors appear in museum collections and online catalogs. There is no mention of his central role in the Holocaust-era looting—no disclosure, no historical context, no restitution.

Csánky’s own artwork—mundane sketches of birds and deer—now hangs in institutions that directly benefited from his crimes. It is entirely plausible that his works are displayed alongside looted masterpieces he orchestrated to seize.

This is not merely historical irony—it is moral inversion. The individual who organized the theft of Hungary’s Jewish cultural heritage is now honored as a cultural contributor.

A call for Reckoning and Justice:

Hungarian museums must break their silence. So must ministries, curators, and archives that continue to benefit from Csánky’s legacy. Cultural institutions have historically insisted on separating “art from politics” or “art from history.” Yet, Csánky’s dual role—as a thief and as an exhibited artist—is a painful reminder of the consequences of erasing uncomfortable truths.

Reckoning requires public acknowledgment. It demands the return of stolen art, transparency about historical injustices, and explicit restitution efforts. It begins, unequivocally, by naming names.

Dénes Csánky helped rob Hungarian Jews not merely of their lives but of their legacies. He constructed the bureaucratic system that enabled mass cultural theft. For these actions, Hungary honored him as a museum official—and now, posthumously, continues to present him as a museum artist.

It’s time to remove Csánky’s paintings from display and restore historical truth to Hungary’s national cultural institutions.

- Hungarian Holocaust Microfilm Archive, Zekelman Holocaust Center:

- Reel 145, Slide 351 – Hatvany crates transferred to museum custody.

- Reel 145, Slides 393–395 – Inventory of looted Jewish artworks.

- Reel 145, Slides 420–429 – Museum intake of looted cultural property.

- Reel 143, Slide 4, Slides 66–70 – Institutional coordination and redistribution plans.

- Hungarian National Gallery Artist Entry for Dénes Csánky:

https://en.mng.hu/artworks/178390/ (Accessed July 2025) - AskArt Biography (archived):

https://www.askart.com/artist/Denes_Csanky/11024880/Denes_Csanky.aspx (Accessed July 2025) - Holocaust Art Recovery Research (Reels 143-145): Detailed archival inventory, documented involvement of Hungarian institutions and officials, key victim cases, and confiscated property lists.