Cutting Paper Portraits of Strangers: from Subway to Classroom

The title Lu gives himself – “master paper portrait cutter” – is one he carried for five decades. This 63-year-old Chinese art teacher also knows carving, sculpting and calligraphy. “Arts are intertwined,” Lu says in Mandarin.

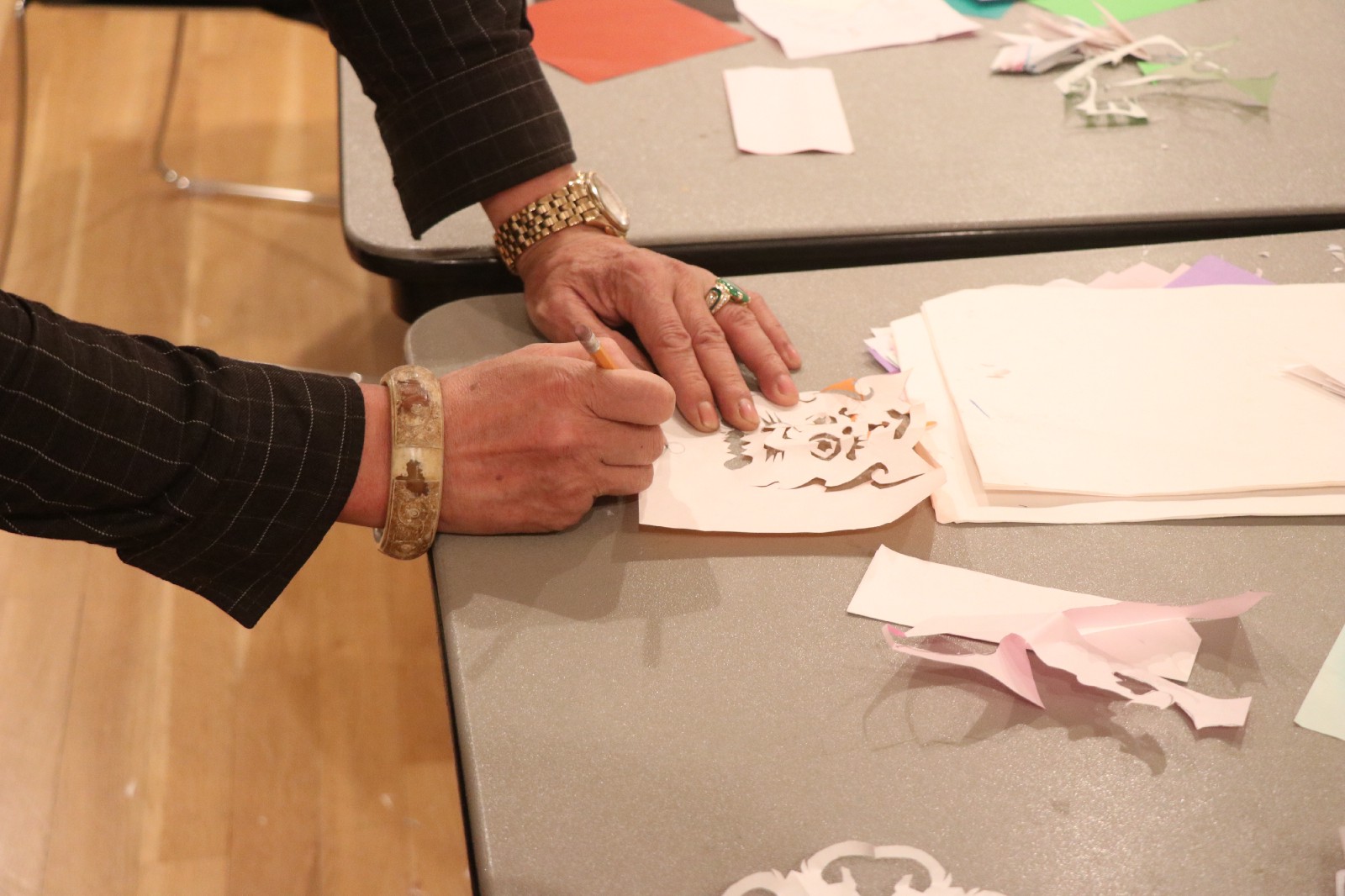

“Jackson, you don't listen to me. You are breaking the scissors and giving me trouble.” Mingliang Lu gently grabs the scissors from Jackson’s right hand and strokes his hair, pretending to be angered by this 4-year-old’s clumsiness. “Put the scissors inside and take a U turn,” he says. “Scissors don't move. Only paper does. See? Now cut.”

In a bright classroom downtown in the New York Chinese Cultural Center, six children sit at a long table listening to Lu demonstrate how to cut out a fish. Giggles, casual chats and the sound of scissors fill the room.

The title Lu gives himself – “master paper portrait cutter” – is one he carried for five decades. This 63-year-old Chinese art teacher also knows carving, sculpting and calligraphy. “Arts are intertwined,” Lu says in Mandarin.

Lu has an impressive resume: his paper-cutting artwork has been exhibited in the American Museum of Natural History; clients have paid up to $3000 dollars for his customized marble carvings; he once cut paper portraits of 120 guests in five hours at a wedding.

Nevertheless, he says art has become a mere hobby.

“I am just an ordinary teacher,” Lu says. “I just want to teach traditional Chinese art to American kids.”

Lu always wears dark jackets. Under slightly messy black hair, his eyebrows angle upward. Whenever he smiles, his eyes fill with energy and delight.

Lu started exploring paper-cutting at five with his father, who encouraged him to learn the fine arts.

Coming to America in the ’90s, already a well-known artist in China, Lu felt ready to pursue his American dream. Before long, he understood that life here wasn't as easy as he’d imagined.

“At home I was capable of being an art teacher in universities,” Lu says, sighing. “But at that time, without a work permit and English skills, I was nothing.”

To make a living, Lu worked as a waiter and delivery man at Chinese restaurants, earning enough to pay the rent. But he always knew that he wanted something else.

“My co-workers kept joking at me, saying ‘Mingliang, we know you are not going to stay long.’ And I said, ‘Yes. how can I stay long knowing I am an artist deep inside?’”

Then in 1996, Lu was diagnosed with lung cancer. He grew as skinny as a skeleton, but after successful surgery, he survived with one healthy lung. The disease was a signal, Lu thought, that he had to put his life back on track.

“After surgery I wasn't able to do manual work,” Lu says. “So I told myself, maybe going back to the arts is the best way for me to live.”

He made himself a street artist.

Lu started drawing tourists’ portraits in Times Square, then moved his one-man stand to SoHo to sell carvings. When he returned to Times Square years later, the portrait artists that he’d befriended were replaced by younger immigrant painters.

“The paintings did not resemble the people they drew,” Lu recalls. “So I teased them by saying ‘I can do better portraits with my scissors,’ and that’s how I the idea of cutting paper portraits occurred to me.”

For 12 years, before disappearing into teaching, Lu was best known as the portrait paper-cutting master in the subway.

He stationed himself at Union Square on the L train every day from 8 p.m. till midnight. After a while, subway riders realized that beyond the bustle of trains where hiphop dancers twined around poles and musicians played guitars, keyboards and plastic baskets, someone was still willing to sit quietly, observe and make magic with a simple piece of paper.

Lu liked to question his subjects while cutting, so that people showed emotion. “You have a handsome face, young man,” Lu might say, moving the paper around his scissors, creating the silhouette of a passer-by who stopped to take a look.

When he works, his eyes move from his subject to the small piece of folded paper. He has poor eyesight, but that does not affect his work.

“My scissors have become my eyes, my brush and my camera,” Lu says. “I can feel how it will look like.”

His admirers include younger Chinese paper-cutting artists like Emily Mock, a first-generation Chinese immigrant and also a paper-cutting artist-in-residence at Wing On Wo, a legacy porcelain store in Manhattan’s Chinatown.

Mock has been creating paper-cutting artwork for Wing On Wo’s year-end shadow puppet show, but mostly moving a knife. One of her pieces, a traditional Chinese dress called Qipao, took more than two weeks to finish, so she understands the difficulty of cutting paper portraits with speed while taking care of the details.

“Using scissors to cut paper portraits while the paper is folded? That takes good spatial imagination,” Mock said. “Just look at the way Lu takes care of the portraits’ details on his subject’s hair. It’s impressive.”

Now teaching children in art schools downtown and at a senior center in Coney Island, Lu feels the burden of an aging body. It’s been almost a year since he cut paper portraits in the subway; working long hours becomes had become too tiring now than ever.

But he has never stopped creating strangers’ silhouettes with his scissors.

Whenever he spots newcomers at the New York Chinese Cultural Center where he teaches on Saturday, he asks if they can spare three minutes so that he can cut a paper portrait.

Those asked look surprised but curious; they never say no.

Once done, Lu pulls out a large sheet, which he has previously signed and affixed his seal to, and adroitly pastes the new portrait on top. He never asks people at school to pay. However, on the subway platform, he charged $25 each.

Over the years, the once isolated, quiet artist has receded, as he has become a beloved and renowned teacher who talks more about his students than himself.

He spends a lot of time with them, not only teaching but befriending them. For weeks, he has been carving a seal for a 15-year-old, Emily Zhang, who started studying with him when she was 4. The seal will be her birthday present.

Zhang and her mother, Kathy Zhou, come to Lu’s Saturday class every week. When Zhang shows Lu the design for her next paper-cutting work, he nods approvingly. After giving tips on cutting with greater caution so that the paper won’t tear, Lu lets Zhang work on her own, while he continues teaching the younger kids.

“Good job, Emily,” Lu says, smiling. “You can start cutting it out.”

Zhang’s mother has known Lu for more than a decade. They’ve ultimately become friends who invite each other to family events.

“Lu encourages Emily to create her own designs, even though she’s still a teenage girl. He believes in her and treats a child’s imagination seriously,” Zhou says.

Zhang, now a Stuyvesant High School student, says she has found haven in paper-cutting. Busy with schoolwork from Monday through Friday, she finds that weekend arts save her from stress.

“Teacher Lu makes me realize that paper-cutting is more relaxing than sleeping,” Zhang says.

At the end of his one-hour class, Lu pulls out files from his huge backpack, stuffed with papers and tools, to create individual portfolios for each student, so that “they can show their proud parents what they have achieved.”

“I always tell my students that they can only be the number one. Anyone that comes second is not my student,” Lu said. “Don’t be intimidated by things that glow. You will become the best in the industry if you persist in doing the same thing for 50 years.”