“‘Blessed are the poor in spirit’, but at the age of 48 I’m no longer so blessed with that quality.” David Claerbout

Having trained as a painter at the Nationaal Hoger Instituut voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp, Belgian artist David Claerbout has become better known for his work with photography and moving images. His work plays with the boundaries of both mediums, questioning our relationship to the visual image and asking us to engage with his work on an intellectual as well as aesthetic level. Claerbout’s works often include elements of sound and visuals that create environments that are almost immersive in nature.

Having trained as a painter at the Nationaal Hoger Instituut voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp, Belgian artist David Claerbout has become better known for his work with photography and moving images. His work plays with the boundaries of both mediums, questioning our relationship to the visual image and asking us to engage with his work on an intellectual as well as aesthetic level. Claerbout’s works often include elements of sound and visuals that create environments that are almost immersive in nature.

We spoke to David Claerbout about his work and challenged him to explain the conceptual difference between a manipulated image and an alternative fact.

Artdependence Magazine: How important is knowledge of history to you?

David Claerbout: ‘Blessed are the poor in spirit’, but at the age of 48 I’m no longer so blessed with that quality.

I profoundly distrust art that targets a certain effect through the knowledge of history. This often results in short-lived art that doesn’t amount to much more than illustrations with a ‘frisson’. There is a secret that great art shares with consumerism, and that secret is the management of desire through a blind spot. If one’s full knowledge of history includes this variable, then I agree that knowledge of history is important.

AD: What is photography to you? Is manipulating photos comparable to alternative facts?

DC: Your questions certainly provoke an entertaining thought - the comparison between facts/alternative facts and factual/manipulated photography. Photography simulates (in the digital age this is how we describe it) an analogy to the real. This is what Roland Barthes described as the denotative powers of photography, also known as a ‘message without a code’.

Our situation is certainly different from Barthes, but the recognition of the analogy to the real is alive, albeit in a purely ritualistic way out of respect for the transformative powers it once had. It would be taboo to regard photography as a mere construction. We are not ready to lose its magic. Suppose that the ‘lens’ would cease to be the gateway to the real, the consequences could be catastrophic for our visual culture. The act of manipulating photographs is almost as old as the invention itself. So I would recommend treating facts carefully, just as I would treat the obvious existential depth of a photograph with distrust but not with paranoia. All facts are alternative, just like photographs show a universe by showing a fragment.

AD: Where did the idea for the series Die reine Notwendigkeit/The pure necessity now presented at Sean Kelly Gallery come from?

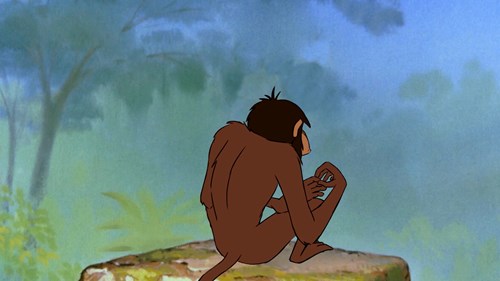

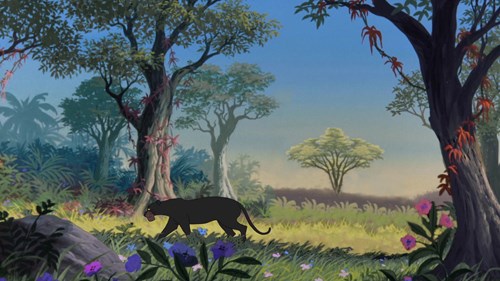

DC: I was researching for another piece that was going to be about useless fear for oneself, expressed through the fear for animals. The protagonists (a wolf and a dear), stood waiting in front of a closed tent in the middle of the forest, early in the morning with the last smoke still coming from the campfire. In order to study their behavior I filmed hours of footage in animal parks. At one point, I was allowed to join the guard inside the wolves’ cage, which was rather uneventful, filming their social rituals but most of all their sleep. That is when the idea changed into a piece based upon the Jungle Book, a typical energetic animation, bursting with life. That is when the idea came to take away the energy of 1967 and beyond, while retaining the form of the film.

AD: How did you go about getting this project off the ground?

DC: Somehow, I knew that this work had the potential to wreck my studio, but I didn't expect to have to start a new animation studio in order to get things done. At peak point the studio employed around 15 professionally skilled animators. There were several moments where I considered giving up, but not in my head. The first crisis came in the first year of production when I realised that every frame had to be newly hand drawn, and could not, as I had hoped, be animated in a 3D program. The characters simply lacked soul. My mistake was to think that lacking soul would be ideal. I realised at that point that taking away the energy in the original would require a lot of effort.

By then, I had invested so many resources on The pure necessity that stopping seemed like admitting to an expensive mistake and continuing into the unknown seemed more adventurous, so that is what I did, disregarding time and expenses until they ran out. Most often, I finance my work with my own savings. In this case however, I got some welcome support by a patron of the Stadl Museum, and the work is now in their collection, largely thanks to curator Martin Engler.

All images: David Claerbout, Still from Die reine Notwendigkeit/The pure necessity, 2016. Single channel video, HD animation, color, stereo sound, 60 minutes, looped. © David Claerbout, Courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly, NY.