When artworks feature in works of fiction – be it novels, films, theatre pieces, poems, – they can serve multiple purposes: they can be mere decorations, function as a conversation piece, or they can play an important metaphorical role. Let’s take a closer look at one specific artwork in the 2003 film titled Mona Lisa Smile.

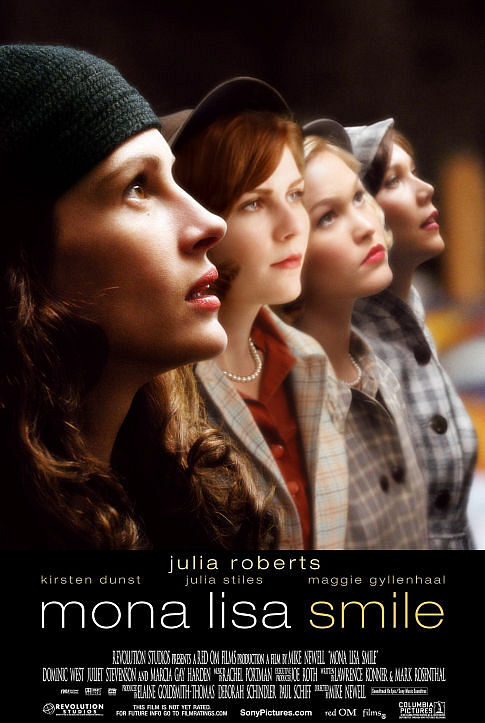

The film Mona Lisa Smile was directed by Mike Newell and written by Lawrence Konner and Mark Rosenthal. The cast stars Julia Roberts in the lead role, but also Kirsten Dunst, Julia Stiles and Maggie Gyllenhaal, among others. The film is set in 1953 and starts Katherine Watson, an art history teacher played by Roberts, moves from California to New England to teach at the prestigious Wellesley College, a private women’s college. We quickly notice the new teacher is progressive, liberal thinking, and this is immediately contrasted with the more traditional and conservative style of the school’s management and students. The students seek an education, yet seem somehow to realize – and perhaps enjoy – the fact that their lives will soon revolve around marriage and keeping a successful household, rather than a career. To Watson, this is revolting. She strives to make the women in her class think for themselves and question the values society imposes on them.

Jackson Pollock, Number 1 (Lavender Mist), 1950, oil, aluminium and enamel on canvas, 221 x 299,7 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Jackson Pollock, Number 1 (Lavender Mist), 1950, oil, aluminium and enamel on canvas, 221 x 299,7 cm. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund.

Art as Metaphors

In an early scene in the film, we see Watson’s first class. The slides she shows dutifully follow the written syllabus. It soon becomes clear that the students have already received and read the entire syllabus, and can reproduce all the information in it. Watson is thrown off by this fact. However, in a next class, she defiantly shows them a slide of the work Boeuf Écorché (Carcass of Beef) (1925) by the Belarus-born French artist Chaïm Soutine. The students are at a loss, as this painting is not in their syllabus. Watson encourages them to look at the work of art in a personal, yet critical manner, and to discuss it.

This scene sets the tone of the film: the students seem to blindly ‘follow the rules’, and Katherine Watson, the progressive teacher, offers new perspectives by showing and saying things they are not used to seeing or perceiving as ‘good’. The film clearly revolves around this contrast between conservative and progressive thinking, and specifically when it comes to the position of women in society. It poses itself as a ‘feminist’ film perhaps. The reviews of the film were rather mixed and lukewarm. Claudia Puig of USA Today wrote, for instance: ‘it's Dead Poets Society as a chick flick, without the compelling drama and inspiration... even Roberts doesn't seem convinced. She gives a rather blah performance as if she's not fully committed to the role... Rather than being a fascinating exploration of a much more constrained time in our social history, the film simply feels anachronistic.’

The film does feel anachronistic, mainly because the behaviour and attachment to traditions of the young Wellesley students is exaggerated – almost to the level of them being caricatures. Katherine Watson, however, feels like she is a 20th-century character with outfits inspired by the fifties. All this is perhaps intentional, for the sake of contrast. In all this, artworks play the part of metaphors.

Very early in the story, we see Watson looking at two slides during her train ride to New England: one of the painting The Dessert (Harmony in Red) (1908) by Henri Matisse and Les demoiselles d’Avigon (1907) by Pablo Picasso. Theoretically, both works could symbolize different takes on a woman’s life which will be developed in the film: the woman in Matisse’s painting is sitting quietly at her dinner table, looking very modest and with her gaze turned away from the viewer. Picasso’s painting, however, depicts naked women in a brothel, unembarrassed to look the viewer in the eye (albeit with their abstracted, cubist faces). They could, in this context, represent the free spirit of the main character.

Throughout the film other artworks play a metaphorical role. For example, a ‘paint by numbers’ set of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1889) is used by Watson as an example of how in life, we want to be guided: we are not invited to think for ourselves, but to follow numbers mindlessly to achieve a realistic copy of the original masterpiece. At the end of the film, when the school year ends, all students from Watson’s class paint her different ‘paint by numbers’ versions: the one more expressive, the other ‘stricter’, as an expression of their understanding of her lesson, and more broadly as a sign of their unique individual characters.

Lavender Mist

The one piece of art that plays a pivotal role in the film, however, is a painting by Jackson Pollock. In a key scene, Katherine Watson takes her students on an excursion to what could be an artist studio, or an art school, perhaps even the back chambers of an art gallery. It is not clear how far from Wellesley College they are, how the group arrived there, how this visit was arranged, nor what Watson’s relation to this ‘Joe’, who lets them in, is.

As they enter and ‘Joe’ greets Watson, other visitors are seen looking at paintings and sculptures. ‘Your timing is perfect,’ says Joe, as he points to the center of the large industrial-style room. As soon as the camera turns to the large wooden crate, the lid falls down and the painting Number 1 (Lavender Mist) (1950) is revealed. Bam! A real Jackson Pollock emerges in front of the students’ eyes. A wet dream for art teaches and art students alike. And something which would be practically impossible to achieve nowadays, but seems no problem for Robert's fictional character in the fifties (the film is set only three years after the painting was created), whom we must assume is on friendly terms with someone very close to the artist, or someone who – in this fictional universe – just bought his painting.

Julia Roberts’ character Katherine Watson stands in front of Jackson Pollock’s Number 1 (Lavender Mist) in Mona Lisa Smile.

Julia Roberts’ character Katherine Watson stands in front of Jackson Pollock’s Number 1 (Lavender Mist) in Mona Lisa Smile.

At first, silence. Then, the students start whispering things like ‘That’s Jackson Pollock’ and ‘I hope we don’t have to write a paper about this.’ Watson, allowing herself a personal preview and examining the work closely, wittily counters this with ‘Do yourselves a favor. Stop talking and look.’ Gradually, the students come closer and the camera goes over details of the work, highlighting its particular texture and the dynamics of the paint’s splashes and drips.

I must confess that whenever I watch this film, I mainly look forward to this one scene. The suspenseful opening of the crate, the load ‘bang’ when the lid drops, the dramatic turning of heads and the timeless silence following the first look at a Jackson Pollock painting: it is typical Hollywood cinema, but I’m sure it appeals to anyone with a heart for modern painting. I would dare to say it is the only moment in the film where a piece of art is actually the centerpiece – except perhaps the scene in which ‘Carcass of Beef’ by Chaim Soutine is unexpectedly shown on slide by Watson, and where she asks her students to analyse it.

Embodiment of Change

Number 1 (Lavender Mist) is, without any doubt, one of Pollock’s most recognizable masterpieces. It was acquired by Washington DC’s National Gallery of Art in 1976, being one of the last ‘classic’ Pollocks to transfer from a private to an institutional collection. The work is a perfect embodiment of the revolutionary ‘dripping’ technique which acquired the artist such fame between 1947 and 1951. Oftentimes, the now legendary article in Life Magazine in 1949 is quoted as the catalyst for Pollock’s fame. The title ‘Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?’ signals his celebrity-like status, but is also a sign of the times: this was only the start of a time in which living contemporary artists acquired this rock star-like fame and media attention (also often accompanied by an attitude coherent with their status). Of course, in 2000, Pollock’s eventful life and character were the subject of a very well-received film by Ed Harris, who was nominated for Academy Awards both as director and as lead actor.

‘On the canvas was not a picture, but an event,’ Harold Rosenberg wrote in 1952. Along with other abstract expressionists, Pollock altered the way art is done, but also the way it is conceived. Number 1 (Lavender Mist) is a perfect example of this: a painting, as many of Pollock’s hand, that does not represent any figurative or narrative concept, but that can be stared at for hours. Astonishingly, the painting contains no lavender – or any similar colour for that matter. The intricate and almost illusionary web of white, black and grey shades has a quasi-magical colour radiation, leading the art critic Clement Greenberg to offer the work its second title.

Jackson Pollock featured in Life Magazine, 1949

Jackson Pollock featured in Life Magazine, 1949

It is worth mentioning that the camera and lighting in Mona Lisa Smile offer the painting a more lavender-like shade, and this is probably intentional in the hopes of conveying the work’s title but also an idea of the way it can be perceived in real life. The painting, and the almost two-minute scene containing its dramatic revelation and the characters perceiving it, stands for a pivotal moment in the film’s narrative. The silence in the scene is meaningful: it is a metaphor for the student’s perspectives changing, their minds opening, and a symbol of the invitation the think for themselves, to experience art (and therefore life), ask critical questions, and make their own judgements. It is symbolic of a change in the history of art, and in the characters of this film.

Sources

About Art, ‘Behind the Art in the Movie Mona Lisa Smile’, YouTube, 2021, last access November 29th, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gph9Xv9CQog&ab_channel=AboutArt

Emmerling, Leonhard. Jackson Pollock. Cologne: Taschen, 2009.

Glueck, Grace, ‘Pollock’s ‘Lavender Mist’ Sold To National Gallery in Capital’, The New York Times, 1976, last acces November 29th, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/1976/10/06/archives/pollocks-lavender-mist-sold-to-national-gallery-in-capital.html

Harris, Ed (dir.), Pollock, Brant-Allen Films, Fred Berner Films, Pollock Films, 2000.

National Gallery of Art, ‘Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist)’, last access November 29th, 2021.

https://www.nga.gov/collection/highlights/pollock-number-1-1950-lavender-mist.html

Newell, Mike (dir.), Mona Lisa Smile, Revolution Studios, Red Om Films, 2003.

Toynton, Evelyn. Jackson Pollock. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2012.