Art in Fiction: A Clockwork Orange

When artworks feature in works of fiction – be it novels, films, theatre pieces, poems, … – they can serve multiple purposes: they can be mere decoration, they can function as a conversation piece, or they can play an important metaphorical role. In this series Tamara Beheydt takes a closer look at art in fiction, starting with one of her favourites: the film A Clockwork Orange (1971).

When artworks feature in works of fiction – be it novels, films, theatre pieces, poems, … – they can serve multiple purposes: they can be mere decoration, they can function as a conversation piece, or they can play an important metaphorical role. In this series I take a closer look at art in fiction, starting with one of my favourites: the film A Clockwork Orange (1971).

Of course, A Clockwork Orange is first and foremost a book: it’s a novel, written by Anthony Burgess and published by William Heinemann in 1962.[1] I must confess I sometimes tend to oversee this – the film being an iconic piece of cinema, written for the screen and directed by Stanley Kubrick and first appearing in theaters in 1971. As it happens, this year marks its 50th anniversary. As a true fan of fiction, and of the story, I have read the book and seen the film. The first only once, the second, many times. It is of no use comparing both – other authors have done this and will continue to do so in the future, I’m sure. What interests me in this essay specifically, is Kubrick’s choice for one particular artwork in one particular scene, which, however, binds the whole film together.

A Clockwork Orange is narrated by its main character, Alex DeLarge, a youngster who frequently and joyously engages in what he terms ‘ultra-violence’. With his ‘droogs’[2] – his three fellow criminals, whom he considers his followers – he goes on a rampage every night: burgling, fighting, raping. After being arrested and charged with murder, he then receives an experimental treatment, a behavioural therapy which is supposed to give him a strong aversion towards violence and sex. The story, set in a futuristic yet dystopian city, can be read as a comment on (juvenile) delinquency, meaningless violence, prison management, psychology and freewill.

Movie poster for A Clockwork Orange. Source: Encyclopedia Brittanica

Movie poster for A Clockwork Orange. Source: Encyclopedia Brittanica

The first few scenes of the film are a rather rapid follow-up of crimes and acts of violence committed by Alex and his gang: from the beating of a drunken homeless man and the fight against Billy-Boy’s gang, to the invading of the home of the writer F. Alexander[3] and his wife, in which Alex famously sings ‘Singing in the rain’ whilst beating the author and raping his wife. It is worth mentioning that the song is a spontaneous addition of the lead actor, Malcolm McDowell, and a stroke of genius when it comes to impersonating his character, especially since music in general plays a very important role in the entire story.[4] It is precisely his acid humour, that makes the film so diabolically cruel and yet surprisingly bearable.

A rocking murder weapon

In the scene entitled ‘The cat lady’s house’, the gang infiltrates the house of a woman who lives alone on a so-called ‘health farm’, surrounded by her cats. She is nameless, referred to only as ‘catlady’, even in the newspapers later reporting on the event. When the lady refuses to let Alex in, even though he rings her bell and cries, quite convincingly, through her letterbox that ‘there has been a terrible accident’ and that he is wounded, he enters through a small window on the first floor.

Already in the first shot of the scene, when the catlady is doing some stretching exercises surrounded by several cats, the work Rocking Machine (1970) by Herman Makkink can be seen in the background. It is a white polyester sculpture of an erect penis and testicles (heavily enlarged: 76 cm long), created so that it could (potentially) rock.

As the catlady returns from (not) answering the door, she enters the room and the camera is placed so that the phallic shape of the sculpture points at her. A subtle, comic, yet uncanny premonition of what is to follow. As she finishes her phone call to the police (having been alarmed by the reports in the newspaper, of the events at F. Alexander’s house the night before), we see Alex entering the room through the same door, equally having the Rocking Machine pointing at him. He remains in the doorframe, as the catlady scares and tries to chase him away with feeble threatening remarks. He delicately touches the sculpture, initiating its rocking movement. As the rocking speeds, the catlady becomes more upset.

The Rocking Machine ‘pointing’ at the catlady. A premonition of what is to come.

The Rocking Machine ‘pointing’ at the catlady. A premonition of what is to come.

Her exclamation ‘Leave that alone, don’t touch it! It’s a very important work of art!’ is a slight exaggeration. On an international level, Makkink is probably still best-known as the artist of the sculpture featuring in A Clockwork Orange. He is better known in The Netherlands, having also received many commissions for public artworks there. Born in The Netherlands, but having travelled to Japan and the United States at a young age, the artist settled in London in 1966. He acquired a studio at SPACE, an artist organization, and this is where Kubrick saw and bought two of his pieces to be featured in A Clockwork Orange. Indeed, Makkink’s Christ Unltd (1970) is installed (and filmed through ingenious and rhythmic close-up shots) in Alex’s bedroom. Makkink returned to Amsterdam in 1972, moving on to remain active as a sculptor and an arts teacher through most of his life.[5]

Only a few moments later in the scene, as the catlady tries to attack Alex with another object, he picks up the phallic sculpture, holding in front of him as a weapon; the shiny white of the piece almost blending with his white costume. While he jumps around making stabbing gestures, the catlady falls. Alex then moves on to punch her in the head with the heavy sculpture. Is this attack a symbolic rape, a metaphorical magnification of many other examples of the ultra-violence committed by him? Are the close-ups shots of her lips – where the punch lands – readably metaphoric for a vulva? It is, in any case, the crime for which he will be arrested and imprisoned, as the cat lady later succumbs to her wounds in the hospital, and therefore one of the most pivotal moments in the story.

Phallic imagery

Rape and sex (or as Alex likes to call it ‘the old in-out, in-out’) are very present in the storyline of A Clockwork Orange, mainly as an exemplary act of ultra-violence. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that other erotic, and more specifically phallic imagery is spread throughout the film. While visiting a record store, Alex flirts with two girls sucking on phallus-like lollipops and moves on to invite them to his bedroom. In several scenes, most notably upon invading the catlady’s house, and F. Alexander’s house, Alex and his droogs wear masks. Alex’s mask in particular is interesting, as it has a long, penis-shaped nose. It does, vaguely, reference Venetian masks, namely that of the ‘Medico della peste’ character of the Venetian carnival, carrying a beaked mask in which herbs were hidden to cover the smell of plague victims.[6] But upon a closer look, and mainly thanks to the more or less realistic skin-like colouring, Alex’s mask leaves little to the imagination and symbolises one of his most frequently committed acts of violence.

Makkink’s sculpture, being the most blatantly graphic phallus in the film, has something of a timeless ritual charisma. Partly because of its white immaculate colour, it resembles monumental stone phalluses as found, among others, in the temple of Dionysus on the island of Delos, Greece. In the cult of Dionysus – a god of human and natural fertility – the phallus was a much-used symbol: ‘At (these) Dionysian festivals, large wooden, metal or stone phalluses were carries around in processions and dedicated to Dionysus.’[7] In cultures around the world and through centuries, the phallus represents fertility, power and life, and is visible in sculptures, in architecture, or as an amulet. Phallic bowl and vases in pre-Columbian cultures, for instance, were created to serve and drink fertility potions.[8] In the Enlightened west, and once the phallus comes back into art in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (after being banned for mainly religious reasons), only its erotic connotation remains, with the symbolism of fertility moving to the background.[9]

It is clear beyond a doubt that the phallus in A Clockwork Orange stands rather far from being a fertility symbol. It refers to it, but can, in this context, be read just as well as a grotesque magnification of a dildo. It’s rocking movements possibly implicate those of a sex toy, but also mirror Alex’s frequently used and remarkably rhythmic term for sex: ‘in-out, in-out’. Its innocent white colour refers to classical sculpture (marble or stone), yet forms a notable contrast with the violent and as Alex himself mentions ‘naughty’ content of the piece. In addition, it seems a perfect extension to Alex’s white costume – incidentally (ironically?) equipped with a codpiece.

Could we even go as far as to read the phallic sculpture of Makkink as an antithesis or a response to the very present cats in the scene? Culturally and historically, the cat is also often a symbol of fertility; in ancient Egypt in the form of the goddess Bastet, but also in Germanic mythology, where the animal is associated with the goddess Freya.[10] In Dutch (or by extension, Western) painting, both cats and dogs are often symbolizing lust and unchastity.[11] And of course there is the more ‘vulgar’ association with a woman’s ‘pussy’. As touched upon before: could the scene be read as a battle between female and male genitalia? As a metaphorical sex (or rape) scene? Kubrick has succeeded in having a work of art play an extremely crucial role in his film; on symbolic, aesthetic, and choreographic levels, and in the overall storyline. ‘A very important work of art’ indeed, when it comes to the film classic that became A Clockwork Orange.

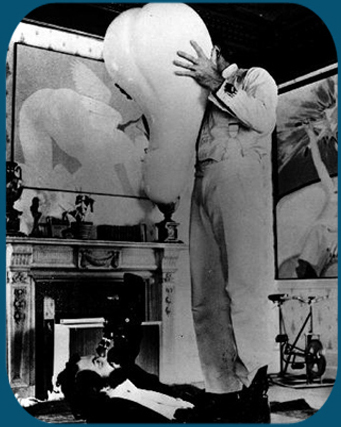

On the set of A Clockwork Orange: Stanley Kubrik films Malcolm McDowell, holding The Rocking Machine.

____________________________________________________

[1] Burgess, Anthony. A Clockwork Orange. Londen: William Heinemann, 1962 (2012).

[2] Alex and his friends use a very unique kind of slang invented by Burgess, called Nadsat, with Slavic inspiration on the one hand and some terms sounding rather childish on the other hand. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nadsat (last access 25th October 2021).

[3] The film does not actually explain its title, A Clockwork Orange. In the book, however, it refers to an essay written by F. Alexander, about the kind of treatment Alex will receive, making him into a ‘good civilian’ but also ‘a clockwork orange’: organic on the outside, mechanic on the inside – without free will. The film version of F. Alexander does mention, in a phone conversation: ‘Recruiting brutal young roughs into the police; proposing debilitating and will-sapping techniques of conditioning. Oh, we've seen it all before in other countries; the thin end of the wedge! Before we know where we are, we shall have the full apparatus of totalitarianism.’

[4] Alex has a great love for classical music, and especially Beethoven (or, as he calls him ‘Ludwig Van’). The 9th symphony is actively used in his aversion therapy, leading him to become sick whenever he hears the piece. ‘Singing in the rain’ receives a similar kind of function, when Alex returns to the home of F. Alexander after having been imprisoned. F. Alexander is visibly triggered and sickened by hearing Alex hum the song again.

[5] The Herman Makkink Estate, ‘The Rocking Machine’. https://www.therockingmachine.com/herman-makkink. Last access 21st of October 2021.

[6] Culture Trip, ‘A Guide to the Masks of Venice’. https://theculturetrip.com/europe/italy/articles/a-guide-to-the-masks-of-venice/. Last access 21st of October 2021.

[7] Mattelaer, Johan J. The Phallus in Art & Culture. History Office European Association of Urology, 2008 (revised from a previously published Dutch edition), 23-24.

[8] Mattelaer, 115-117.

[9] Mattelaer, 134.

[10] Locht, Marthy, Dieren in de kunst. Fauna in de schilderkunst van de late middeleeuwen tot het einde van de negentiende eeuw. Utrecht: SU De Ronde Tafel, 2013.

[11] Rijks Museum, ‘Honden en katten’. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/rijksstudio/onderwerpen/honden-en-katten Last access October 25th, 2021.