3D Scans show rare glimpse Inside Ancient Egyptian Burial practices

Thanks to Halloween tales and Scooby-doo specials, mummies are often thought of as scary or grotesque creatures with glowing eyes and tattered wrappings. In reality, mummified human remains offer us an incredibly personal insight into the lives of individuals who lived more than 3,000 years ago.

New CT scans taken at the Field Museum are giving scientists fresh perspectives on mortuary practices and the lives and deaths of individuals in ancient Egypt, as well as past museum conservation efforts. These scans allow scientists to virtually remove the barriers that stand between them and the mummified individuals and help to highlight each deceased person’s individuality and reveal what their community thought important enough to bring with them to their eternal afterlives.

In a study spanning four days, 26 individuals were put through a mobile CT scanner parked just outside the museum. This technology functionally created thousands and thousands of X-rays of the individuals, which are digitally stacked together to provide a 3D picture of what’s inside. The scans gave researchers a peek behind the wrappings that have helped to preserve these people for more than 3,000 years.

“From an archeological perspective, it is incredibly rare that you get to investigate or view history from the perspective of a single individual,” said Stacy Drake, Human Remains Collection Manager at the Field Museum. “This is a really great way for us to look at who these people were – not just the stuff that they made and the stories that we have concocted about them, but the actual individuals that were living at this time.”

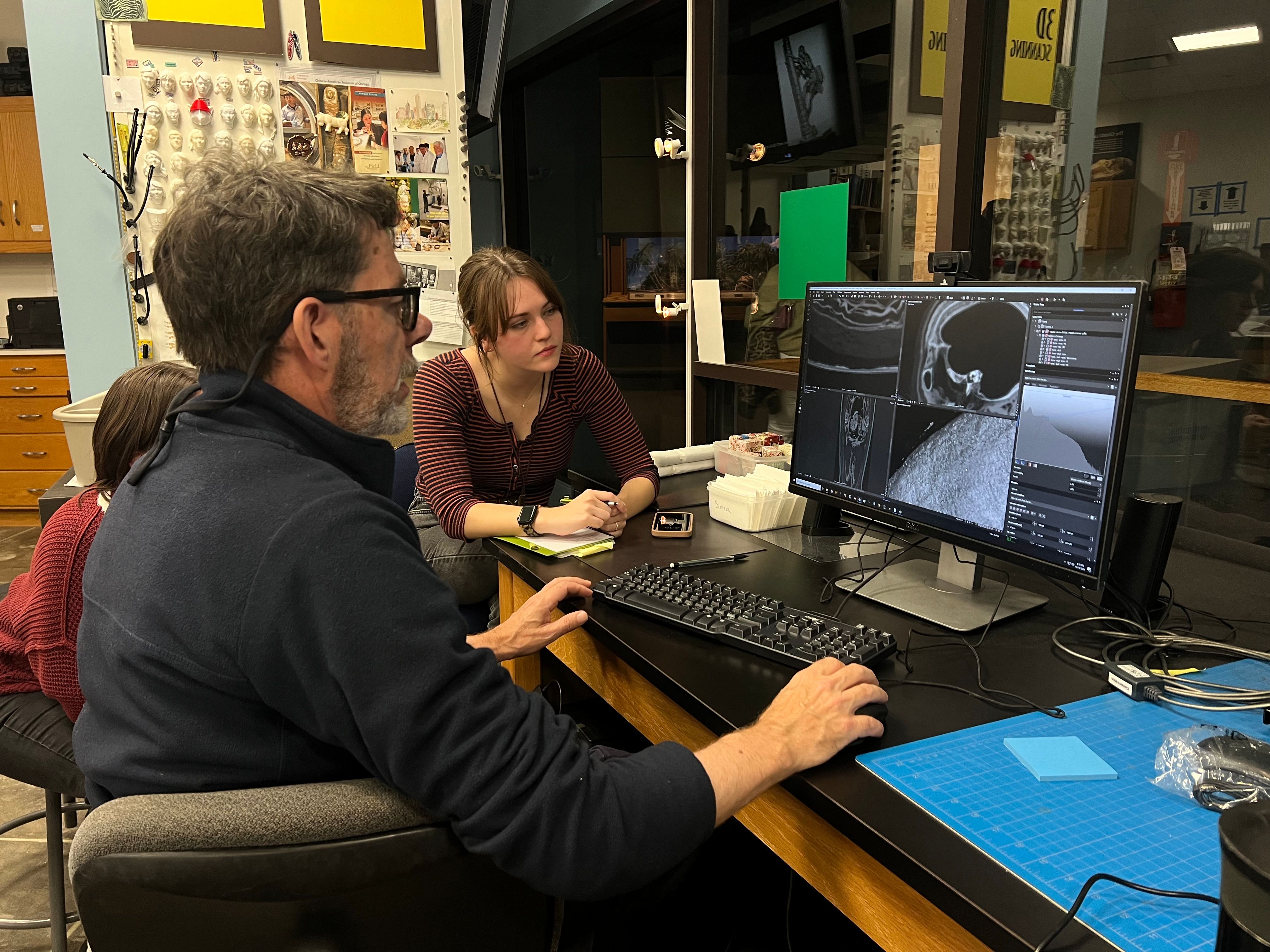

JP Brown analyzes the composite scans of a mummified individual on the computer. Field Museum 2024

The study of these individuals has just begun as scientists work to digitally pull back layers to see what remains of the physical bodies and their burial objects. Even so, museum staff have already been able to answer some of the mysteries of the most famous remains at the museum.

Lady Chenet-aa lived during the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt, during the 22nd Dynasty. That puts her remains at 3,000 years old and in remarkable condition. Thanks to the new scans, scientists can now place her in her late 30s or early 40s at the time of her death. The loss of several teeth and significant wear on the remaining teeth indicate the food she ate contained stray grains of sand that were tough on the enamel. The scans also reveal that Chenet-aa had supplementary eyes placed in her eye sockets to ensure they came with her to her afterlife.

“The Ancient Egyptian view of the afterlife is similar to our ideas about retirement savings. It's something you prepare for, put money aside for all the way through your life, and hope you've got enough at the end to really enjoy yourself,” said JP Brown, Senior Conservator of Anthropology. “The additions are very literal. If you want eyes, then there needs to be physical eyes, or at least some physical allusion to eyes.”

For years, Chenet-aa and her cartonnage, the paper mache-like funerary box that contains an embalmed body, have puzzled researchers. With no visible seam and only a small opening at the feet, there seemed to be no point of entry for Chenet-aa’s body to have been placed in her cartonnage – this created a sort of locked-mummy mystery.

Thanks to the CT scans, conservators are now able to see the underside of the cartonnage for the first time. “You can start to see that there's a seam going down the back and some lacing,” said Brown.

They now know that rather than the cartonnage being constructed around the body, the mummy was stood upright and then the cartonnage coffin was softened with humidity to the point it was flexible enough to mold around the body. Then a slit at the back was cut from head to foot, it was opened up, lowered down over the wrapped body, and closed again. Once it had been laced down the back, a wood panel was put in at the feet and then pegged in place to keep everything together.

The mummified individual known as Harwa has long been a favorite at the Field. Also from the Third Intermediate Period, he lived about 3,000 years ago. The scans taken have revealed that Harwa lived a relatively cushy life as the Doorkeeper of the 22nd Kingdom’s granary. Images of his spine reveal that even at his increased age (early to mid-40s) he shows no immediate signs of ailments that would come from performing repeated physical labor. Furthermore, his extremely well-kept teeth reinforce his high social status as he had access to high-quality foods.

Harwa has an extensive legacy of having a very full afterlife. Archival Field Museum publications share Harwa’s tale as the first mummified person to fly on an airplane in 1939. Upon arrival in New York City, he was welcomed with a variety of activities beyond the wildest dreams of an ancient person, including visiting a Broadway show. When his two-year stint on display at the New York World’s Fair ended, he became the first mummy to get lost in luggage, as he was accidentally sent to San Francisco rather than back home to the Field Museum.

This anecdote, while wild, showcases the import of our evolving consideration of the care we give for the remains of mummified individuals in the collections. Today, our standards of care for human remains emphasize them as individual people deserving of dignity and respect. Each of these people had lives and families, and the CT scans offer us a very personal snapshot into their pasts. The care with which these individuals were embalmed, and the personal details in their physical remains, reveal how little humanity has changed over the millennia.

This is the beginning of the new information these CT scans will tell us about these individuals. Scientists expect the study to continue over the course of the next year as they digitally peel back the layers and discover more details that otherwise would have been lost to time.

Main Image: The mummified remains of Chenet-aa under a CT scanner