There was a time when a trip to Europe could be described as ‘Grand’. Long before bargain flights, crossing the continent was a major undertaking. It was part education, part shopping trip, and if you weren’t wealthy, or at least in the retinue of someone who was, it was beyond your means. Grand Tours flourished between the 17th and 19th centuries, a time during which the nobility stocked their stately homes with artworks and antiquities from the Mediterranean lands. In 2015, they still have an exclusive aura, or did so until the arrival of Pablo Bronstein.

There was a time when a trip to Europe could be described as ‘Grand’. Long before bargain flights, crossing the continent was a major undertaking. It was part education, part shopping trip, and if you weren’t wealthy, or at least in the retinue of someone who was, it was beyond your means. Grand Tours flourished between the 17th and 19th centuries, a time during which the nobility stocked their stately homes with artworks and antiquities from the Mediterranean lands. In 2015, they still have an exclusive aura, or did so until the arrival of Pablo Bronstein.

Bronstein is known for doing one thing very well: drawing buildings and ornamentation. He has a scary knowledge of architecture from classical Europe. But perhaps thanks to a birth overseas (in Buenos Aires), he approaches the classical heritage of the British nobility with little reverence. So there could be no one better to spearhead an festival which revisits The Grand Tour as its class-ridden theme.

Four UK venues are linking up to explore the Tour, and work by the Argentinian can be seen across two of these: Nottingham Contemporary (home of contemporary art) and Chatsworth House in Derbyshire (home of the Cavendish family since 1549). Bronstein has sized up the latter’s numerous treasures, in order to intervene, curate and comment on what he’s found.

“They’ve got some very, very strong points to their collection,” he tells me, via phone from his base in London. “There's no doubt they've got some grade A old master drawings, probably the best collection of old master drawings outside of the Royal Collection, in private hands. It is that good”. But in the next moment he will add, with academic authority: “They don’t have a fantastic collection of paintings”.

Colossal Roman marble foot wearing a sandal (BC 150-50) © Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth. Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees.

Bronstein knows his onions, but his work plays hard and loose with fact. At Chatsworth he presents a large architectural drawing of a grandiose façade, a projected design merely to house a portrait by Rembrandt. If you’re not at your most alert, you may take this in as just another relic. But if you notice the Rembrandt (which is also here, on the adjacent wall), you realise how absurd the drawing is.

“The viewer relationship is one of potentially grabbing some people and ignoring others,” he says, and claims to be, “interested in a kind of subtle realisation that something might not be entirely right with the object”. So in a setting where most of the artworks and antiques shout at you, Bronstein’s intervention whispers, and it tells you that something is very wrong.

Pablo Bronstein, Design for a large clock in the Louis XV style, representing The Sun Rising over the Desert. 2012. Ash L'ange Collection. Courtesy Herald St. London

“Chatsworth is a kind of funny place. All convention within museums can be seen as quite funny,” he says, when asked about the slyly comic element in his work. But he also notes: “I’m not poking fun so much at museums, as at what I think we want to see when we go there”. You might come away from this show chastened.

Whether picking through the storeroom at Chatsworth, browsing his own working library of architecture books, or watching documentaries on archaeology, Bronstein is attuned to the make believe which makes history. And as he says: “I'm not so interested in what was really there before. I like a history of falsification, you know, and wishful thinking.”

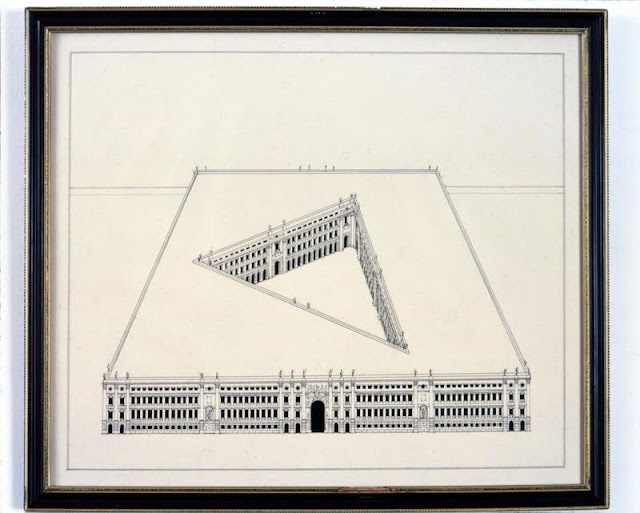

Pablo Bronstein, Large Building with Courtyard, 2005. Ash L'ange Collection. Courtesy Herald St. London

In a sense, the Grand Tour itself was an odyssey of wishful thinking. Says Bronstein: “There was a real industry in the falsification of history and the falsification or works of art and they were there, really, to con English aristocrats out of a great deal of money.” The artist relates the existence of a gang of forgers who were fabricating antiques with help from the likes of architect Robert Adam and artist Piranesi.

As one might expect in a collection as extensive as that of Chatsworth, there are “some odd things” to be found at the home, and Bronstein has curated some of these for his concurrent show in Nottingham. “We borrowed a pair of candelabra that use antique Roman porphyry vases and rework them into candleholders,“ he says, but that is just the beginning of it.

Bolton & Quinn. Pablo Bronstein at Chatsworth as part of the Grand Tour c. Hugo Glendinning

In its largest UK loan for 30 years, some 60 objects from the stately home can now be seen at Nottingham Contemporary. It includes furniture, silverware, Delft porcelain and paintings, and has the full backing of the Duke of Devonshire. It brings you up against a marble foot from a colossal Roman statue. It includes the coronation chairs of William IV and Queen Adelaide. And many of these works are framed by a serial drawing of the Appian Way.

This too is a piece of subversion by Bronstein. “It’sentirely fabricated,” he assures me. “It's 100 percent bullshit. There isn't a single reference to building that is consistent throughout the actual building, and there are some structures there that are deliberately nothing to do with, either Rome or, the French academy, or Neoclassicism.” Look closer and you will find anachronistic Baroque architecture. You may or may not miss a Vegas hotel in the style of Venturi.

Pablo Bronstein, Theatre Section with Stage Design for an Oliver Cromwell Ballet. 2014. Ink and watercolour on paper in artist’s frame Courtesy: Herald St, London and Franco Noero, Turin

Like many of his architectural studies or follies, Bronstein’s frieze-like Appian Way reveals a degree of obsession which an account of his process does nothing to dispel. He works from the foreground to the background in the design stage, then he works from back to front when colouring them with washes of ink. This gives the piece aesthetic unity, even if it pings off in different directions in terms of architectural style.

Indeed, whether in the East Midlands, or the ICA, or with his representatives Herald Street, there is really no mistaking the elegance and quite wit of these single-minded drawings. In an age of promiscuous practices he defends his narrow approach: “Drawing is a very good medium to communicate in. It’s quick. You can move through a lot of ideas very quickly. It is as a medium a lot less theatrical than painting is”. He decries painting as too illusionistic and atmospheric.

Delft ovoid flower vase by Adrian Koeks (c.1690) © Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth. Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees

So when it comes to drawing architecture, Bronstein will freely admit to an obsession. But there is method in this madness: “What it's allowed me to do is refine the craft and to have an inventory of ideas that you can talk through to yourself in a lot of depth”. But the artist is modest about his scholarly credentials.

“I’m not a historic curator,” he insists. “But it’s not like I’m choosing work because I think it’s fun and funky”. Of course he isn’t; now, as then, the Grand Tour is a serious business.

Image above: Bolton & Quinn. Pablo Bronstein at Chatsworth as part of the Grand Tour c. Hugo Glendinning

ArtDependence Magazine is an international magazine covering all spheres of contemporary art, as well as modern and classical art.

ArtDependence features the latest art news, highlighting interviews with today’s most influential artists, galleries, curators, collectors, fair directors and individuals at the axis of the arts.

The magazine also covers series of articles and reviews on critical art events, new publications and other foremost happenings in the art world.

If you would like to submit events or editorial content to ArtDependence Magazine, please feel free to reach the magazine via the contact page.