Echoing the elements that have driven the artist’s style throughout his extensive career as a painter, the works included in Guillermo Kuitca’s last exhibition at Hauser&Wirth in London mirror the artist’s liberation from external references to focus on a universe that seems to be completely his own. In this series of recent works (most of them created between 2014 and 2015) painting itself is the first motivation.

“The pictorial, the physicality, the actual tools and the more basic practice of the painting is what drives me nowadays.” - an interview with Guillermo Kuitca

Echoing the elements that have driven the artist’s style throughout his extensive career as a painter, the works included in Guillermo Kuitca’s last exhibition at Hauser&Wirth in London mirror the artist’s liberation from external references to focus on a universe that seems to be completely his own. In this series of recent works (most of them created between 2014 and 2015) painting itself is the first motivation.

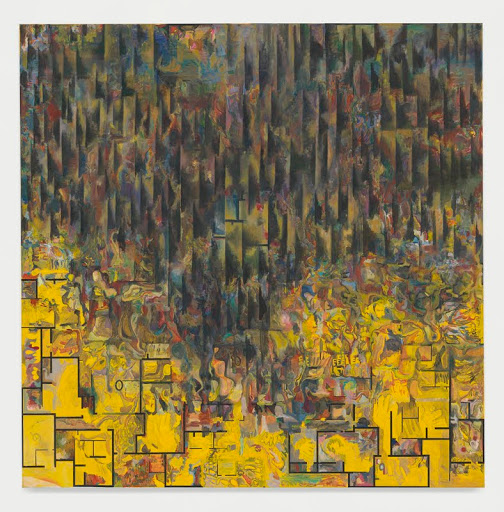

To say that this series represents a zenith in his career as a painter would sound like a form of condemnation, an assumption that this is the beginning of the end. Far from that, it could be said that the audience will see fragments of a pictorial world that Kuitca has created throughout the years, where he integrates the elements that have defined his career at the same time that he pushes the boundaries of his practice. While combining architectural and theatrical elements stemming from his 1980 and 1990 works and making use of the unique Cubistoid style that defines Kuitca since his series Desenlace (2007), the artist reconciles large-scale gestural abstract paintings with a precise and rational understanding of spatiality and the presence of figurative elements, such as the presence the human figure in some of the pieces.

The solo exhibition at Hauser&Wirth London, which runs until 30 July, is accompanied by an exquisite monograph co-published by Snoeck and Hauser&Wirth Publishers and with a contribution by Michael FitzGerald, curator of ‘Post-Picasso: Contemporary Reactions’ for the Museu Picasso of Barcelona in 2014.

Artdependence Magazine: When did you decide to become an artist?

Guillermo Kuitca: I think it was so early that I never had to take a decision. Probably when it was time to take a decision it was already too late because somehow, from my earliest memories, I always remember myself with artist’s tools, like brushes or crayons or paint. So I’m still not sure if I took a decision to be an artist.

The practice came first and maybe the decision came much later—or maybe I forgot that there was a decision to be taken.

Guillermo Kuitca, Untitled (Exodus), 2015. Oil on canvas. 200 x 630 cm / 78 3/4 x 248 in. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Guillermo Kuitca, Untitled, 2015. Oil on wooden panel. 40 x 120 cm / 15 3/4 x 47 1/4 in. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Guillermo Kuitca, Untitled (yo mujer), 2015. Oil on wooden panel. 50 x 200 cm / 19 5/8 x 78 3/4 in. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne

AD: One of your influences is Pina Bausch. How did the choreographer affect your work?

GK: I saw Pina Bausch’s company very early in my life and in the companies’ life as well, in 1980. Back then the company was not as famous as it became later.

They came to Buenos Aires as part of a Goethe Institut tour at a very obscure time in Argentinian history, during dictatorship.

I was very shocked by what I saw. I had always liked theatre, not particularly dance, but it was a field that I liked very much. I thought, “If I want to do something, that’s what I want to do, not what I’m doing”. I wanted to do something else. I think that’s the influence when I talk about this choreographer. It makes me ask how I can create a condition in my own painting that could be a field for a theatrical experience.

Through the years there was a process. If you see my works in the eighties you see a clear influence from her work in terms of settings or theatrical moments or dramatic scenes. Then they became quite different, because somehow I took the drama towards the audience rather than to the stage. So the result is seating plans, a large suite of theatre seen from the stage.

Somehow I can’t point out an influence in this body of work, but I can point out her influence as a major force that makes you look for the drama in small units of it.

It was a very radical time for the company, they hardly dance it was more like Tanztheater. It was the time when they did Kontakthof and Bandoneon, very dry, very still.

I don’t know how to tell you if her influence in my work is still visible today, but I still think it was a major force in the first encounter and I think it lasted for a long, long time.

Guillermo Kuitca, Untitled, 2014. Oil on wooden panel. 230 x 106 x 4 cm / 90 1/2 x 41 3/4 x 1 5/8 in. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Guillermo Kuitca, Untitled, 2015. Oil on canvas. 40.5 x 60.5 cm / 16 x 23 7/8 in. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne

Guillermo Kuitca, Untitled, 2011. Oil on canvas. 40 x 30 cm / 15 3/4 x 11 3/4 in. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne

AD: How would you describe your art to a child aged five?

GK: Maybe he would do it for me. Most kids at five don’t expect you to describe. Description is such a grown up habit that probably doesn’t have much place in a discussion with a kid.

Ultimately, it’s funny because when you’re looking at a work with a kid you’re normally driven to ask the question: “what do you like? What don’t you like? What do you see? What don’t you see?”. He or she won’t expect a description. They won’t need it.

AD: Tell us about your recent work ‘Untitled (Exodus)’ (2015), included in your current exhibition at Hauser&Wirth.

GK: That’s the main work in the exhibition. I had to transform my studio in order to make this very long piece. I can work with very large pieces, but not as wide, so I created a whole wall. In a way I prepared a lot of things in order to make this piece without knowing at all what I was going to do. Somehow the studies were from working on my space rather than on the work itself. I believe that I prepared my space rather than preparing myself to work on the image itself.

It started in many directions and there is this language that is echoing, a lot of modernist references that I’m not that specific about. I know that they might be ghosts of early cubism, and also later cubism and some Latin-American modernism, but none of them are quotes, not that I saw Picasso, Braque, Gris, Torres García and said “ok, that’s it”. It was more like a language that had the resonances of this cubistoid language and I found that I could move through this language very fluidly, without doing any historical or heavy references to art history at all.

Still, when I place this threshold in the middle, the whole dynamic of the work changes. I found that the work suddenly became many things. It became the backstage of a theatrical space that we didn’t know. It became a narrow passage for history. There is this historical vagary that could be absorbed through that passage.

There were days that I thought there was an exodus that doesn’t come or go through the threshold, but it goes across. I feel that if I sit long enough in front of the work I will see it passing, but not coming or going through, just passing right to left, left to right. Maybe it’s a group of people, maybe a historical moment.

The title was a little bit difficult to find because I knew there was a title for the piece, though I thought it was a bit heavy-handed. Therefore there is an “untitled” first and “exodus” is the way it echoes in my mind.

Guillermo Kuitca, Untitled, 2003 – 2015. Oil on canvas. 196.5 x 196.3 cm / 77 3/8 x 77 1/4 in. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Alex Delfanne

AD: What you said about that element going across and not through is interesting because history itself can travel in different directions, not necessarily in a one-directional line.

GK: Yes, I like that. When I was creating the painting, the Syrian immigration crisis was pumping out in the news and I always felt uncomfortable to tie some works to current events. I still don’t think I was portraying anything related to that. Still, I cannot decide whether this tragic and painful news is or is not in my painting; perhaps not the actual affairs, but the subject of exodus. That is what made me hesitant of carrying that weight over the painting. I think the work has enough imprecise or even poetic references that are not so literal, at least not as an artist describes current events.

It happens sometimes that even if you do a work completely isolated from any historical events sometimes when you place a title like that one, you can’t stop anyone from making their own interpretations and connecting one thing to the other. That’s completely out of my control.

AD: How has your work evolved over time?

GK: It’s gone through many phases, sometimes more theatrical, others more architectural. For a decade I worked with architecture plans, not in a minimalistic or clean way, but like a muddy architect with a very technical side. After that, over many years, my work was facing alternatively theatre, architecture, and music and only lately it seems that it’s purely connected with painting. I don’t think I paint for painters, or that this is art for art’s sake. Somehow the pictorial, the physicality, the actual tools and the more basic practice of the painting is what drives me nowadays, while in the past there was always something to refer to. I think these works are more independent. It seems that the work has been liberating itself from references. Hopefully.

AD: How does the city where you live influence your work?

GK: I was born in Buenos Aires, I’ve always lived there. Actually, I don’t live far from where I was born. I feel that somehow even if I was all over the places, I never quit a very small area.

It’s a huge city, it’s very chaotic. It’s one of those cities where somehow you have to decide how are you going to live in that reality and whether you’re going to be a filter for that or the one who processes that that and it eventually becomes your art, or if you are going to build fences around a reality that is sometimes harsh, sometimes interesting - it’s always interesting, actually. It’s a city with very high contrast and I tend to think that my work alternatively had been a defence to what surrounds it, more reclusive, or more permeable. It’s either one or the other. It’s not about conscious decisions; sometimes it happens without even noticing.

I like the city, I like working there. Some of the Latin American megalopolis are hybrids, so you can pretty much make out the city you want. If you can of course.

My studio is in a very nice neighbourhood and I feel that I can develop my work in some kind of limbo, which sounds like a negative thing, but it’s not totally bad when you have to make art.

Installation view, 'Guillermo Kuitca', Hauser & Wirth London, 2016 Photo: Ken Adlard

Installation view, 'Guillermo Kuitca', Hauser & Wirth London, 2016 Photo: Ken Adlard

AD: What would you be if you weren’t an artist?

GK: In my dreams, I would probably have been a tennis player or a brilliant lawyer. In my reality I think that I would have been probably a theatre person, maybe in the directing field. That’s something that I know I have an eye or a tendency for, to find theatricality in big things or small things. But in my dreams, none of that is what I would have chosen to be. I would be someone totally different.

AD: What are your current interests in relation to your artistic practice?

GK: This [the current exhibition at Hauser&Wirth] is a very recent body of work. There are pieces that are not here that are constructions or what I call “paintings or sculptures from inside”. They are almost like pictorial capsules.

I create a space and I want the viewer to physically enter the painting, so somehow these are capsules or constructions where you enter, so you get surrounded or trapped by the painting.

An example of that is my collaboration with David Lynch for the exhibition I organised for the Fondation Cartier in Paris [Les Habitants], where I revisited some of what Cartier has done in the last thirty years and one of the main pieces was a revisitation of an installation that Lynch did about fifteen years ago. I took some elements of that and changed it. I asked him to step in and create a painting out of what I had done. There was also a record of Patti Smith’s voice reading a text by David Lynch and that was part of the sound of the piece.

That piece was particularly multi-sensorial, because you have the sound, the space, and an aspect of changing atmosphere. Some of the structures are more dry, but still you have to step in. In a way, ‘Untitled (Exodus)’ is actually a painting that uses a little bit of that unfolded structure. It’s like a physical passage and you feel almost like the painting is folded around you when you get inside.

These are the sorts of things I’m working on now. Also there are some mural paintings, which are paintings that I don’t have to worry about because they don’t travel. I’m so sick of the problem of some works and working out how to make them travel. I love murals because they stand in a place, so if you want to see them, you have to come, I can’t go after you, I’m here if you want to look at the murals!

Installation view, ‘Guillermo Kuitca. Les Habitants’, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, France, 2014 © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Olivier Ouadah

AD: What do you dislike about the art world?

GK: I don’t know, it’s such an easy target to say things that you don’t like about the art world. To tell the truth, it’s not that I’m going to praise the art world as such, but it became such an easy target to say that there is too much money, too much frivolity, too many party scene or things like that. I’m not a fan of art fairs of course, but that’s nothing original, I don’t know many artists that like going to art fairs.

AD: What living artist do you admire?

GK: Vija Celmins, who was also part of the exhibition at Fondation Cartier.

Portrait above: Guillermo Kuitca © Aaron Schuman

ArtDependence Magazine is an international magazine covering all spheres of contemporary art, as well as modern and classical art.

ArtDependence features the latest art news, highlighting interviews with today’s most influential artists, galleries, curators, collectors, fair directors and individuals at the axis of the arts.

The magazine also covers series of articles and reviews on critical art events, new publications and other foremost happenings in the art world.

If you would like to submit events or editorial content to ArtDependence Magazine, please feel free to reach the magazine via the contact page.