The British Museum has just opened a fascinating new exhibition on the legendary city of Troy, and the mythical ten-year war between the Greeks and the Trojans of which Homer and countless other poets sang. It has a wealth of paintings, vases, sculptures, and other artefacts that testify to the enormous influence of the Trojan war both on the Greeks and Romans, and, to a lesser extent, on later Western culture.

Image: Antin, Judgement of Paris (after Rubens), 2007

The British Museum has just opened a fascinating new exhibition on the legendary city of Troy, and the mythical ten-year war between the Greeks and the Trojans of which Homer and countless other poets sang. It has a wealth of paintings, vases, sculptures, and other artefacts that testify to the enormous influence of the Trojan war both on the Greeks and Romans, and, to a lesser extent, on later Western culture.

The story of the Trojan war was at the heart of ancient Greek culture. Its defining shape was given by two epic poems, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, which were probably composed in the eighth century BC. Little is known about that time, when writing was just starting to be used in Greece. But from the sixth century BC down to the end of the Roman empire a thousand years later, a huge flowering of art, architecture, and poetry bears witness to the pervasive influence of the stories about the Trojan war on every aspect of the classical world. This included the customs, religion and identity of the Greeks (and the Romans too), their literature and even their politics. The Greek word for these stories was mythoi: ‘tales’ whose relationship to the truth was a matter for constant debate.

The shifting relationship between the Trojan myths and their ‘reality’ for the Greeks is acknowledged in the British Museum’s latest blockbuster exhibition, Troy: Myth and Reality. As co-curator Alexandra Villing puts it, the main focus is, appropriately, on the myths’ ‘human truth’, rather than their historical fact.

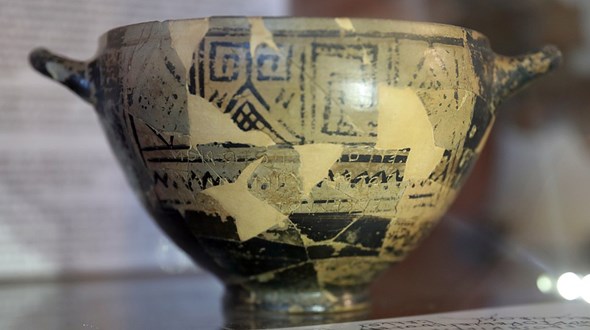

For this reason, the first and largest of the exhibition’s three sections examines, not the historical background to the myths, but the way they were retold in Greek and Roman art. A large number of earthenware storage jars, drinking cups, and wine-mixing bowls, as well as coins and gemstones, testifies to the presence of the myths in people’s everyday household objects from the sixth and fifth centuries BC onwards, in cities across the eastern Mediterranean. Decorated with red and black figures, which are often identified by little captions, the vessels depict scenes from the Trojan story in cartoon-like detail.

The judgement of Paris, the abduction of Helen, the death of Hector and other heroes, the Trojan horse, the sirens singing to Odysseus: all these occur again and again. The subject matter of the objects tells us not only which stories the artists and buyers found most appealing, but also how the artists exercised their inventiveness on familiar themes. In the bowl of a drinking-cup, Odysseus stands over Achilles, who the artist has depicted wrapped up in a blanket (expressive of extreme chagrin), trying to persuade him to rejoin the Greek army and fight against the Trojans. On the side of an amphora, the artist has imagined Achilles and Ajax playing a board game to kill time during the ten-year war.

A silver drachma and an engraved red sardonyx from a signet ring both depict the moment when the hero Diomedes was said to have stolen the Palladium, a statue of Athena, from her temple in Troy. The image on the coin celebrates Diomedes’ success; the gemstone shows Odysseus gesturing at the corpse of the temple attendant Diomedes has just killed, suggesting that his sacrilegious deed will incur divine wrath.

The rape of Helen, and the war which followed, is one of the most powerful myths of the Trojan cycle, but also one which can seem most distant to a modern audience. Why spend ten years, with the loss of so many lives and such destruction, for the sake of a single person? Because, as Homer tells us, her husband’s honour was at stake –– and because she was the most beautiful woman in the world. In a wall painting from the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii (on loan from the National Archaeological Museum of Naples), Helen is depicted about to step onto the ship that will take her to Troy.

The expression in her dark eyes is captivating: she is staring down at something, as if transfixed, while her lips are firmly closed. Is she an innocent victim, no more than a trophy, or is she haunted by the guilt of what she is about to do? The silent painting leaves us with its riddle.

A different Helen appears in a neo-Attic marble relief of the first century BC. She sits on a stool, looking down at her hands, in the posture of a modest bride. Aphrodite has her arm almost maternally round her protegée’s shoulders. The goddess points a delicately suggestive finger in the direction of Paris, who leans casually against the wall on the other side of the room, listening to a youthful winged Eros, who is looking up at him as if in challenge. The goddess Peitho (Persuasion), a favourite of the Athenians’, sits on a pedestal above the two female figures. The pleasingly balanced sculpture implies that Helen and Paris were brought together by mutual desire.

Among so many beautiful works of art, it is easy to miss one of the most important pieces on display: the so-called ‘cup of Nestor’, loaned from the Archaeological Museum of Pithecusae. This is a small, half-broken drinking cup with a simple geometric design that dates from 715 BC.

Nestor's cup at Ischia

What makes it precious is a three-line verse inscription scratched over the paint, which you can just see if you kneel down and catch the light. Not only are these lines one of the earliest examples of Greek writing; they also allude to the Homeric epics, in which Nestor was an ageing warrior. The cup is thus one of the first witnesses to the place of the myths of Troy in the Greeks’ everyday life and imagination.

The fame of these myths may even have reached as far afield as Asia. This is suggested by an intriguing relief panel from a Buddhist shrine, probably made in Pakistan in the second century AD. The panel shows a horse on wheels being pushed towards a gate. A woman, her arms raised as if in fear, stands in a doorway. This may be an echo of the myth of the Trojan horse, which Cassandra, a princess of Troy, prophesied would destroy the city.

The Greeks had always argued over where Troy, if it had existed at all, was located. This argument continued all the way to the nineteenth century, when a German businessman called Heinrich Schliemann, encouraged by previous archaeologists, began to excavate the hilltop fort of Hisarlık in north-west Turkey. Without regard to conservational niceties, and leaving a trail of destruction in his wake, Schliemann tunnelled down into the mound, revealing in the process a series of nine bands of buildings, with associated remains, stretching back to 3000 BC.

Schliemann’s discoveries, and later finds at Hisarlık, are the subject of the second section of the exhibition. The artefacts here, which are mostly very very old pots, are primarily interesting to the non-specialist in the way they evoke a sense of a truly ancient civilisation on a single site. Notable among these is a ‘face pot’ which, rather creatively, Schliemann identified as an ‘owl-like’ image of the goddess Athena, whose temple is mentioned in the Iliad. He concluded that he had discovered the real Troy. Scholars today are still divided as to whether he was right, and, if so, whether there is any historical truth behind the Trojan war.

The majority of the objects from ‘Troy’ are on loan from the Museum for Pre- and Early History in Berlin, where Schliemann exported them in 1880. Unfortunately, his most sensational finds are missing. These consist of a large hoard of gold jewellery and beads, silver vessels, and metal tools and weapons, which he labelled ‘Priam’s Treasure’. Most famous among these are the so-called ‘Jewels of Helen’: a gold diadem and earrings which Schliemann immediately attributed to Troy’s most famous woman. At the end of the Second World War, the jewels and other treasures, which Schliemann had given to the Berlin museum, were plundered by the Soviets. Their whereabouts remained unknown for many years, but in the 1990s they re-emerged in Russia, and have since been on display in Moscow’s Pushkin Museum. Visitors to the BM will have to content themselves with a photograph of Schliemann’s second, Greek wife, Sophia, adorned with the jewels, and modern replicas by the German goldsmith Wolfgang Kuckenberg. The question of who the ‘Jewels of Helen’ really belong to is still unresolved.

The final section is devoted to the post-classical reception of the myths of Troy in a smattering of disparate works. These include a number of versions of the ‘Judgement of Paris’, from a mysterious, strangely Biblical watercolour by William Blake (1806-17), to a chromogenic print by Eleanor Antin (2007), which makes a political point but is otherwise underwhelming.

Antin, Judgement of Paris (after Rubens), 2007

The poster image of the exhibition is taken from a life-size neoclassical sculpture of ‘The Wounded Achilles’ (1825) by Filippo Albacini.

‘The Wounded Achilles’ (1825) by Filippo Albacin

The snow-white marble of the warrior’s skin is so smooth as to look almost clammy; his expression is sentimentalised to the point of self-indulgence. This is a long way from the ‘greatest of Achaeans’ described by Homer – and not necessarily for the better.

The curators are right to stress that the influence of the myths of Troy spread beyond the ancient world into the later Western tradition. But what this exhibition shows, above all, is the importance of Troy to the Greeks’ self-perception, and the stories and images with which they surrounded themselves. For modern Europeans, the two World Wars and the stories which have accumulated around them are arguably more important than any ancient myth. But we have yet to find a Homer.

Troy: Myth and Reality

21 November 2019 – 8 March 2020

British Museum

ArtDependence Magazine is an international magazine covering all spheres of contemporary art, as well as modern and classical art.

ArtDependence features the latest art news, highlighting interviews with today’s most influential artists, galleries, curators, collectors, fair directors and individuals at the axis of the arts.

The magazine also covers series of articles and reviews on critical art events, new publications and other foremost happenings in the art world.

If you would like to submit events or editorial content to ArtDependence Magazine, please feel free to reach the magazine via the contact page.