In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the world witnessed the rise of the Internet, dramatically changing our everyday lives. Digital culture has become an effective and vital affiliate in reaching wider audiences and achieving key objectives for arts and cultural organizations. In the last few years there has been exponential growth in technology - Elon Musk’s SpaceX, the blockchain, cryptocurrencies, Sophia the humanoid robot, and more. But the question that arises is, to what extent has digital culture changed the art industry?

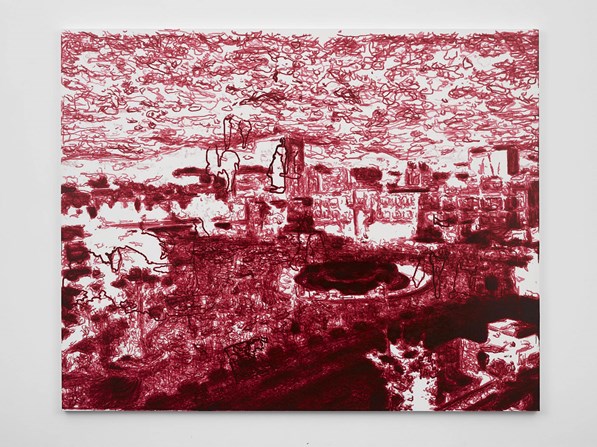

Image: Liu Xiaodong, Weight of Insomnia (Gwangju), 2018 Acrylic on canvas 240 x 300 cm, 94 3/8 x 118 in, Image © Lisson Gallery

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the world witnessed the rise of the Internet, dramatically changing our everyday lives. Digital culture has become an effective and vital affiliate in reaching wider audiences and achieving key objectives for arts and cultural organizations. In the last few years there has been exponential growth in technology - Elon Musk’s SpaceX, the blockchain, cryptocurrencies, Sophia the humanoid robot, and more. But the question that arises is, to what extent has digital culture changed the art industry?

It is undoubtable that in recent years technology has created new opportunities for the art world: blockchain technologies, 3D printing, virtual reality and many more advancements have redefined the art scene. Tech-businesses are cooperating with arts and cultural organisations to create new experiences for clients and audiences. They also help artists find new ways of self-expression.

Matt Hancock, the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sports claims that “Digital technology is breaking down the silos between the cultural sectors, blurring the lines between disciplines – theatre blends with film; computer programming merges with sculpture. We have virtual-reality curatorship, animated artworks, and video games scored by classical music composers.” (Gov.uk, 2017)

In 2018, Christie’s teamed up with blockchain-secured art registry service, Artory, to reinforce buyers’ confidence in the uncertain and opaque art market. This was the first-ever auction sale to be recorded by a secure blockchain technology, allowing clients to maintain their privacy and have a secure and immutable digital record of the history of the artwork they are buying.

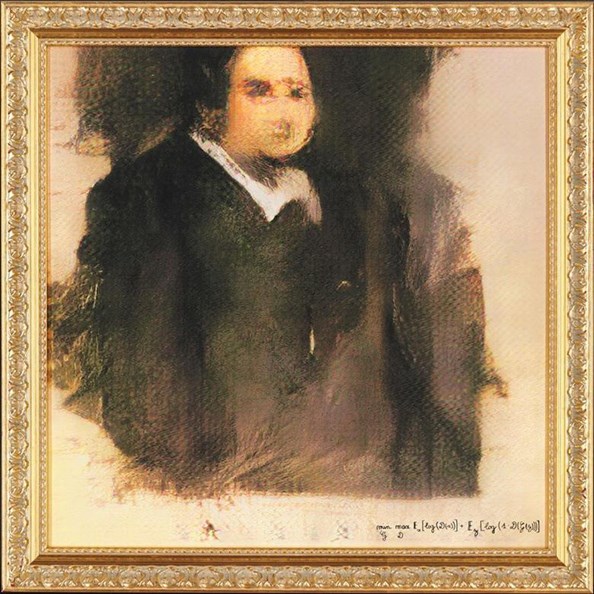

Additionally, Christie’s became the first auction house to sell a painting created by artificial intelligence. On the Prints and Multiples sale, the lot exceeded its estimate by 45 times and the final price realised was $432,500. The work is created by art-collective Obvious, and is a print on canvas depicting a blurry portrait of a man, Edmond de Belamy (Image 1). It is signed with a part of the algorithm that created the artwork. Obvious collective is a group that is exploring the idea of machine learning and artificial intelligence in the art field. The lot sold on Christie’s sale was part of a series of portraits of the Belamy family, and in order to produce the portrait, Obvious had analysed 15,000 images from different periods, which resulted in the creation of the algorithm of the portrait.

"We're looking at these portraits the same way a painter would. Like walking through a gallery, taking inspiration. Except that we feed this inspiration to the algorithm, and the algorithm is the part that executes the visual creation." Gauthier Vernier says to advocate the artistic value of the piece. (Obvious Art 2018)

The portrait of Edmond de Belamy is a combination of the original 18th-century portrait with influences from contemporary art. It confronts the role of the artist in the contemporary art field and challenges artists’ functions in the creation of the artwork’s cultural and financial values.

Portrait of Edmond Belamy, 2018,

Generative Adversarial Network print, on canvas, 2018, signed with GAN model loss function in ink by the publisher, from a series of eleven unique images, published by Obvious Art, Paris, with original gilded wood frame

S. 27 1⁄2 x 27 1⁄2 in (700 x 700 mm.)

Image © Obvious

"This new technology allows us to experiment with the notion of creativity of a machine, and the parallel to the role of the artist in the creation process," says Hugo Caselles- Dupré, co-founder of Obvious collective. (Obvious Art, 2018)

Similarly to A.I. entering the art field, robot-created art is also emerging on the market. In early 2019, London based Lisson gallery staged a show of works created by a contemporary Chinese artist Liu Xiaodong. (Image 2) The works are created using robotic arms and surveillance cameras. Robots could be also taken as a form of A.I., yet in this instance, the artist has full control over the creation of the artwork.

Taking a live feed, streaming data and imagery from an iconic London location above Trafalgar Square, Liu created a painting machine to process this rolling-image feed and transcribe the ever-changing flow of passersby into a complex network of abstract marks on canvas, resulting in a machine-manufactured painting at the exhibition’s finissage. (Lisson Gallery, 2018)

Liu Xiaodong

Weight of Insomnia (Gwangju), 2018 Acrylic on canvas 240 x 300 cm

94 3/8 x 118 in

Image © Lisson Gallery

Unlike Obvious collective, Liu remains in control of the artwork and essentially, he reassesses painting in the age of the Internet, implicitly invoking the present condition of the world. (Lisson Gallery, 2019)

Apart from digital culture intervening with the way art is created it has also penetrated the ways audience perceive, purchase and access art in the last decade. Obtaining art through websites such as Saatchi, Artnet and Artsy gained popularity amongst collectors. These online platforms offer a direct relationship between the artist and the client, as well as broadening the reach-out for artists from around the world. According to Artsy Gallery Insights, 90% of galleries offered art for sale online in 2018. Digital channels are becoming an increasingly important part of driving revenue for art galleries across the globe. (Artsy, 2019)

Social media is a vital part of everyday life; new technologies and applications allow instant access to a wide range of information from whenever you are. Museums and galleries use social media widely in order to reach wider audiences. Museums like the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Louvre in Paris are engaging with their target audience through Instagram and on Facebook by sharing the highlights of their permanent collections and temporary exhibitions. This affects the flow of visitors to the museums by appealing to a wider audience. Additionally, the digitalisation of museums offers better access to collections. For example, the Louvre became the most visited museum in 2018 as they began selling their tickets online, which aided in reducing waiting times. The Victoria and Albert Museum exceeded their visitor flow expectations during the recent David Bowie Is show, partially because of the social media outreach.

All of the above advocates for the extensive influence of digital culture on the art and cultural sectors. The way art is purchased, created, perceived and sold has changed because of the digitalisation of the market and new technologies entering the field. It is interesting to speculate how far digitalisation will go and in what other ways will it alter the art world.

ArtDependence Magazine is an international magazine covering all spheres of contemporary art, as well as modern and classical art.

ArtDependence features the latest art news, highlighting interviews with today’s most influential artists, galleries, curators, collectors, fair directors and individuals at the axis of the arts.

The magazine also covers series of articles and reviews on critical art events, new publications and other foremost happenings in the art world.

If you would like to submit events or editorial content to ArtDependence Magazine, please feel free to reach the magazine via the contact page.