The Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts, known as the ‘Archive of Muses’, is Russia’s largest stored collection of materials relating to the history of national literature, music, theatre, cinema, fine art and architecture. Artdependence Magazine had an opportunity to talk to Tatiana Goryaeva, the director of the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art in order to find out more about the inner life of the Archive and the findings, which are a great pleasure for researchers and collectors and anyone interested in Russian arts.

The Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts, known as the ‘Archive of Muses’, is Russia’s largest stored collection of materials relating to the history of national literature, music, theatre, cinema, fine art and architecture. The archive was established in 1941, created in part using the collections of the State Literature Museum (GLM). It was originally named the Central State Literature Archive (TsGLA). Collections from the Central State October Revolution Archive of the USSR, State Historical Museum, Central State Archive for Old Documents, the State Tretyakov Gallery and other archives were transferred to it. In 1954 it was renamed the Central State Archive of Literature and Arts of the USSR, and in 1992 it got his present title - the Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts (RGALI).

According to a decree from the president of the Russian Federation on 2nd April 1997, RGALI was included in the State code of especially valuable objects of cultural heritage of the Russian Federation. RGALI contains items from institutions in the field of culture, theatre, film studios, specialized educational establishments, publishing houses and public organizations, as well as personal documents, letters and items from writers, critics, artists, composers, theatre and cinema figures.

Artdependence Magazine had an opportunity to talk to Tatiana Goryaeva, the director of the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art in order to find out more about the inner life of the Archive and the findings, which are a great pleasure for researchers and collectors and anyone interested in Russian arts.

Artdependence Magazine: How do items find a place in your institution?

Tatiana Goryaeva: As M.L. Gasparov claimed, "a person is the point of intersection of social relations ... This is most clearly seen in the archive, where you can see a person’s character through letters addressed to him from different persons" (as a side note, his creative laboratory was in the reading room of RGALI).

Archives are a potentially infinite collection of documents, despite the restrictive framework of the criteria of formation. In turn, each source, depending on the context, the goals and methods of its investigation, and also on the personality of the researcher who touches it, offer endless opportunities for interpretation. No one can dispute the fact that letters and diaries are undoubtedly the most reliable historical sources. In letters, we see events and facts, as well as an assessment of those events, and the feelings and experiences of the author in relation to those events. Personal documents fix events and facts almost simultaneously in relation to reality. Letters carry emotional and individual information that is not filtered by time and memory. They fully reflect the retrospective realities. That's why researchers have a special interest in letters and diaries.

We receive several letters that have previously been privately owned. We take them into state storage and archive them. There is always a contract between RGALI and the owner of the archive, in which a separate line specifies the conditions for access to documents. As a rule, the owner limits access to any private correspondence to either a specific time frame or a certain category of users. For example, the wording could be "limit access for all to 50 years" or "access only for research purposes". It’s also very common for the owners of epistolary sources to ask that each individual case be coordinated via them. In other words, we have to ask the owner for permission in writing every time someone requests to view the letters. Over the decades, we have learned that this is the kind of approach that guarantees a person’s private life. We are obliged to observe people’s right to privacy according to the international code of archival ethics.

I am not mistaken in saying that RGALI is the largest repository of epistolary heritage in Russia. The archive contains around 3000 personal holdings that have been collected during 76 years of the Archives' existence. We have millions of stored letters. Among them there are letters not only from Russian figures of literature and art, but also from prominent foreign figures as well.

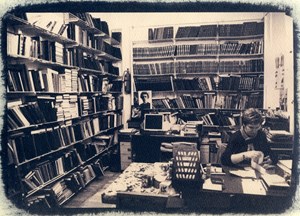

© Vadim Prischepa

© Vadim Prischepa

© Vadim Prischepa

© Vadim Prischepa

AD: What is the oldest letter in the Archive and who was it from?

TG: The majority of the collection covers the period of the XIX - XXI century, although many collections and large holdings contain documents from earlier periods.

AD: Do you have letters from important painters in your collection?

TG: In the archives of artists, along with visual materials, painting and graphics, there are many letters, diaries and travel notes. From the XIX century, there are many letters written by A.A. Ivanov to V.I. Grigorovich (1833 - 1849), I.K. Aivazovsky: M.I. Vladislavlev (1889), N.A. Sultan-Krym-Girey and also letters from M. Taglioni to I.K. Aivazovsky (1842). We also have correspondence between the Vasnetsov brothers: V.M. Vasnetsov and Ark. M. Vasnetsov (1896 - 1915). There is a rich correspondence between M. Vrubel and A. Benois.

Ilya Yefimovich Repin (1844 - 1930) was a Russian realist painter. He was the most renowned Russian artist of the 19th century. His position in the world of art was comparable to that of Leo Tolstoy in literature. He played a major role in bringing Russian art into mainstream European culture. His major works include Barge Haulers on the Volga (1873), Religious Procession in Kursk Province (1883) and Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks (1880–91). A few years ago his letters to V. Bazilevsky from 1918-1929 were prepared and published. During the last thirty years of his life, I. Repin lived in Kuokkala (a municipal settlement in Saint Petersburg, Russia, formerly known as Kuokkala when it was Finnish), where he settled in 1900 with N.Nordman-Severova at her dacha known as Penates. Famous representatives of Russian literature, science and art often gathered at this country home. Amongst them, singers and composers, writers and poets were all welcome guests. Chaliapin, Glazunov, Cui, Liadov, Stasov and many others spent time there.

After 1917 Repin was cut off from his homeland. Lonely, melancholy and torn away from his relatives and friends, he felt lost and unnecessary. Still strong in his creative desires, he lost touch with his home soil. The longing was the most terrible feeling. It overcame him and led him to despair: "Dreary, hopeless feelings randomly, pointlessly climb into the head." The situation was aggravated by the fact that his children were in different parts of the country. Mail that came from abroad was subjected to perusal or did not reach him at all. During this time, Viktor Ivanovich Bazilevsky, a Petersburg theatre lover and patron of art became a messenger for Repin. He had a connection to the theater named after V. Komissarzhevskaya, where Repin’s daughter Vera was working as an actress. 72 letters from this period were received by the collector I.E. Zilberstein from Lyubov Pavlovna Yakushevich. She bought them from the daughter of Bazilevsky. Subsequently, they were stored in RGALI. The major part of the correspondence was preserved in the Archive of the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. Repin died in 1930, and was buried at the Penates. After Kuokkala became a part of the Soviet Union in 1948, it was renamed Repino in his honor. The Penates also became a museum in 1940.

The incredible wealth of epistolary culture is demonstrated by representatives of the Silver Age and the literary and artistic avant-garde of the early twentieth century. These include correspondence from E.G. Guro and M.V. Matyushin, N. Goncharova and M. Larionov, S. Sudeikin, I. Bilibin, and many others. So, the personal store of of Konstantin Somov completely consists of his extensive correspondence. Among his numerous correspondents were Z.I. Grzhebin, S. P. Dyagilev, E. N. Zvantsova, L. S. Bakst, A.N. Benois, V.E. Borisov-Musatov, S.S. Botkin, I.E. Grabar, D.N. Kardovsky, V.F. Komissarzhevskaya, B.M. Kustodiev, E.E. Lansere, V.E. Meyerhold, A.M. Remizova, N. K. Roerich, V.A. Serov and others.

Perhaps the most interesting items are the letters of Kazimir Malevich. Among his correspondents were Mikhail Matyushin, Ivan Klyun, El Lisitsky, David Burliuk, Alexei Gan, Sergei Senkin, brother Mechislav Malevich and others. Research and scientific publication of these invaluable letters show evidence of close communication and creative cooperation, no less stormy than conflicts and contradictions that arise between the artists. In the near future, the first result of the development of this heritage will be published - a two-volume edition of articles and publications prepared by leading art historians in the field of avant-garde.

© Vadim Prischepa

© Vadim Prischepa

© Vadim Prischepa

AD: There is constant research being done in the Archive. Can you give us an example of something interesting that has been uncovered?

TG:Interesting finds do happen, although not that often. The greater joy is that which these items offer to us, the custodians, collectors and researchers. Here are two stories about that.

I once called a lawyer who was supposed to help us solve some archival problems. Whilst speaking to him, we found that his family had kept letters from Alexander Alexandrovich Blok, a Russian lyrical poet. The letters were addressed to their grandmother, a Russian woman named Claudia Petrovna Tsingovatova. There had been a number Blok’s letters in the archive for years but no one could understand the relevance. Finally, we were able to combine the two in order to make sense of the correspondence and tell the whole story.

Discoveries also happen in the reading room. The well-known art critic Andrei Sarabyanov recalls: "I was researching the collections from 1912-1913 in the RGALI, looking at full-scale [cubist] drawings made in Tatlin's studio on Ostozhenka. In this workshop a group of young artists gathered: Popova, Udaltsova, Malevich, Vesnin, Alexander Grischenko. They called themselves "Cubist circle". They captured a series of female nudes, but in a cubist style. Apparently, the albums were simply all over the place. They reveal different hands and it is sometimes difficult to distinguish a Popova from a Tatlin. I found a small portrait of Malevich made by Tatlin. This is a very unique thing because these two artists quickly had a difference of opinion and remained irreconcilable rivals in art for many years. There is even a legend that when Malevich died, Tatlin came to his funeral and said: "I do not believe he is dead, he deceives." So this was the only period when they communicated. This was a small token of their short friendly relations. It is interesting that a little later, in 1913, Tatlin painted a painting called "Portrait of the Artist", already picturesque. In that painting there was another face, more like Tatlin himself, but the small details are the same: a brush, a pencil, a tie. It seems that they originated from Malevich. It was a very interesting discovery."

Fund 3145, list 1, file 625, p.1 - the letter from K.Malevich to M. Gershenzon

Kazimir Malevich, 1933, Self-portrait (detail). Current location: Russian Museum in St. Petersburg

Fund 869, list 1, file 46, p.2-3 - the letter from B.Kustodiev to K.Somov

Fund 869, list 1, file 46, p.2-3 - the letter from B.Kustodiev to K.Somov

B.Kustodiev, Self-portrait in front of Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra, 1912. Current location: Uffizi

Interview translated by Anna Savitskaya.

ArtDependence Magazine is an international magazine covering all spheres of contemporary art, as well as modern and classical art.

ArtDependence features the latest art news, highlighting interviews with today’s most influential artists, galleries, curators, collectors, fair directors and individuals at the axis of the arts.

The magazine also covers series of articles and reviews on critical art events, new publications and other foremost happenings in the art world.

If you would like to submit events or editorial content to ArtDependence Magazine, please feel free to reach the magazine via the contact page.