Born in 1890, Austrian painter Egon Schiele is known as a controversial painter whose work defied all convention. With explicit depictions of the naked human form, he stripped away classical notions of beauty and focused on distorted, elongated figures that seemed to capture the essence or psyche of the sitter.

Image: Egon Schiele - Nude Self-Portrait

Born in 1890, Austrian painter Egon Schiele is known as a controversial painter whose work defied all convention. With explicit depictions of the naked human form, he stripped away classical notions of beauty and focused on distorted, elongated figures that seemed to capture the essence or psyche of the sitter.

Schiele was born into a humble family. In his early childhood he grew fond of drawing. His family and teachers often referred to Schiele as an unusual and reserved in character. At the age of 15, Schiele’s father died suddenly of syphilis, leaving Schiele in the care of his uncle, who allowed him to pursue his artistic passions.

Egon Schiele - Nude Self-Portrait

Schiele soon went to study at the liberal Kunstgewerbeschule school of art but by request from his teachers he was transferred to the more traditional Akademie der Bildenden Kunste in Vienna. He found the style of teaching at the school conservative and restrictive. In 1907, searching for new tutorship, Schiele sought out Gustav Klimt, who took a liking to the young artist and offered him mentorship and friendship. In Schiele’s early works, Klimt’s influence is clear and there are strong parallels between the work that the artists produced, particularly during the period from 1907-1909. Impressed by his art, Klimt invited Schiele to exhibit at the Vienna Kunstschau in 1909. It was there that Egon encountered the work of van Gogh other European artists and began to create more expressionist pieces. Klimt and Schiele’s friendship lasted until Klimt’s death in 1918, when Schiele painted Klimt on his deathbed just weeks before his own early death.

After leaving the Academy der Bildenden Kunste, Schiele began to experiment with a more individual style, moving away from Klimt’s teaching and focussing more intently on human sexuality and the naked form.

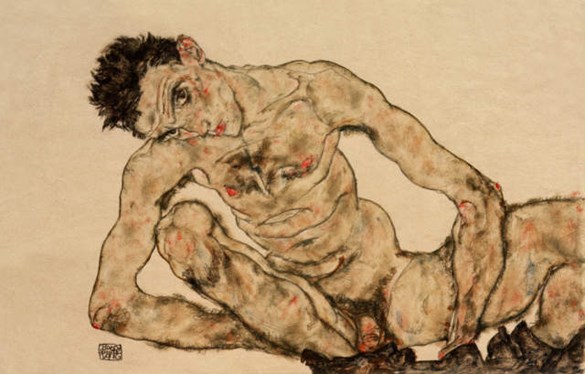

Like Klimt, Schiele’s images included distorted forms and played with the familiar human body, but he took the sexual connotations of the work further, particularly in a series of self-portraits in which he appeared naked and sexually open on the canvas. He began his series of nudes around 1910, developing his unique style of painting the human body as pale, contorted and somewhat sickly.

Schiele’s approach to the naked form was radical for its time, and can still shock today. Even the most progressive of Schiele’s contemporary artists were challenged by his work. It was unapologetic, bold and revealing, taking his subjects and contorting them into sexualised, raw beings. It was said that during a sitting, Schiele used a free flowing painting style and maintained an almost constant gaze on his model, creating an intimate relationship.

In 1911, Schiele met Walburga Neuzil and began a relationship with her, using her as his model (she has previously say for Gustav Klimt). Looking to escape the social scene in Vienna they fled together to a small town named Krumau, where Schiele’s mother had lived, but were not welcome there and were eventually forced to leave by residents who objected to their artistic practices, including paying young girls from the village to pose for paintings. Having moved to another small town West of Vienna, Schiele was arrested in 1912 and sent to prison over accusations of seducing a young girl and creating pornographic images. He was sentenced to 24 days in prison.

In 1915, Schiele married Edith Harms who lived across the street from his studio, expecting to keep Walburga as a mistress. Furious at the betrayal, she left him immediately. Just days after his wedding, Egon Schiele was conscripted into service as World War I continued. His active service saw him working in a POW camp and continuing to paint from a small, disused store cupboard. He returned to Vienna in 2017 but sadly succumbed to the Spanish Flu in 1918, passing away just days after his wife Edith, who was heavily pregnant at the time. Despite dying at the young age of 28, Schiele produced more than 3,000 drawings.

Schiele defied the norms of portrait painting in his era, refusing to pander to the norms of beauty and creating instead his intensely personal depictions. His depiction of the naked body in particular feels more than sexual. It is almost emotional, charged with energy and unsettling.

Schiele often served as his own model, creating self-portraits that were highly unusual and revealing with strong erotic tones. His vision of himself appears to be stark, emaciated and without limitations.

The naked human body is intimate and private, usually reserved for a select few viewers. It’s usually reserved for private moments, and yet Schiele repeatedly renders his naked form on canvas, to be displayed publicly. In doing so, he at once challenges normal convention and ideas of decency, and also invites the viewer in to his private, personal world. He is literally baring all, presenting his raw self. Having fought for the right to create his art and pushed against the boundaries of convention, Schiele seems to be exercising the ultimate freedom of self-expression.

As culture dictates that we keep the human body clothed, shielded and hidden from view, depictions of nudity have become symbolic of exposure, vulnerability and weakness. With Schiele’s defiant, open stance in his self portraits, he defies this expectation, instead appearing comfortable with the exposure, relishing the chance to appear as his true self in front of unknown viewers for generations to come. In his nudity, Schiele is stripped of the traditional trappings of ego and self-expression, and yet his image appears very expressive, bold and defiant.

For Schiele, nudity is socially unacceptable, rebellious and controversial, yet it is the truth – the purest identity stripped of all pretence and artefact. In a world in which Schiele was often outcast or different, he chooses to represent himself naked, contorted and yet unapologetic.

ArtDependence Magazine is an international magazine covering all spheres of contemporary art, as well as modern and classical art.

ArtDependence features the latest art news, highlighting interviews with today’s most influential artists, galleries, curators, collectors, fair directors and individuals at the axis of the arts.

The magazine also covers series of articles and reviews on critical art events, new publications and other foremost happenings in the art world.

If you would like to submit events or editorial content to ArtDependence Magazine, please feel free to reach the magazine via the contact page.