I’m not working towards a body of work that has a consistent and recognisable style. My work is eclectic. The only thing that I try to be consistent with is the poetic conversation that I have with my audience. Today I mostly work in film, video and photography, but that might change. Who knows. All I hope is that I can continue to be a fulltime artist until I die.

When my girlfriend and I were in college, we often went to the cinema together. More than in laughter in the dark, I revelled in sitting silently next to her and noticing with a warm skin-tingling feeling that we were both moved by the film we had chosen to see. It is a rare feeling that lingered long after the credits and that was confirmed by being both lost in thought, loaded silences on the walk home, and short bursts of ardent sentences that tried to grasp what we had experienced. One of the films that made a profound impression on us was The Invader (2011) by Belgian-born and New York-based video artist Nicolas Provost. I remember that the art context and the titillating teaser whetted my interest, but I could not anticipate that the story of Amadou, a black immigrant that washes up on a nudist shore and ends up in Brussels, would be world class. From the dreamy, sensuous and rosy tracking shot at the beginning to the nightmarish and surreal ending, the desperate attempt of a sad, amiable, lustful and brutal man to eke out an existence in an unpitying city and – more importantly – to feel a spark of human warmth, was as idiosyncratic and wryly romantic sculpted by Provost as it was acted by Issaka Sawadogo and scored by Evgueni and Sasha Galperine. Even though I saw hundreds of other films since, his feature debut is still one of my absolute favourites.

When I told him the gist of the above at the opening of his mid-career retrospective ‘The Perfect Wave’ in Waregem art centre Be-Part in March 2014, he embraced me. A gesture that shows what kind of a man and artist he is. With his art he wants to touch and connect us. In a recent interview he stated: “Empathy is what is most important. It is our wiring, what makes us human.” Even though some of Amadou’s actions can hardly provoke any sympathy, he is still as complex and conflicted as we all are, a temperamental man moreover who faces adversity and inhospitality. He sinks in the kind of immigrant hell that adopted many forms in the past year and that appealed to us via harrowing images. It is no surprise then that Provost is less inspired by art than the world we live in. But the way he wants to reach our hearts is by using the codes and conventions of a parallel one, one that he deems as important as ours: cinema and the language it has developed since its inception.

A film fanatic, who, halfway through his art course, emigrated to Norway, started making video art there at the turn of the millennium and finished a course in script development at the Binger Filmlab in Amsterdam after his return to Belgium, he dismantles a mass medium to compose a new story that is more than a mere decomposition. As another author noted, his films are a stylistic condensation of moods and arcs, rather than a theoretical, let alone critical reflection on the appearances of the dream machine that is the film industry. Again, the fictional reality of film is as meaningful to him as the often bleak reality we live in. That is why he believes in self-explanatory images, images that remind us of the ones that are ingrained in our memory, be it by film tropes or popular culture in general. He is not out to confuse, but to allure, so that he can affect us and give us a mesmerising and self-reflective experience. “The connection of mind and emotion is the climax that I look for.”

Nicolas Provost, Exodus, Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp, Belgium

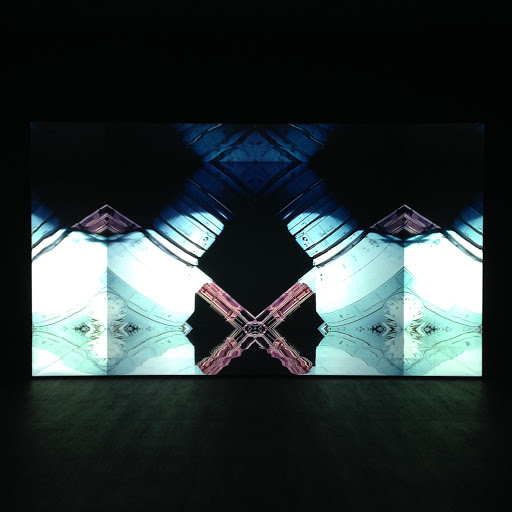

Those realities are closely interwoven in ‘Exodus’, a two-part solo exhibition in the Belgian arts centre de Warande that consists of a four-channel video installation in one gallery and a mirrored video projection in another. The four CinemaScope projections in the first gallery show serene scenes in an iconic setting: the American West. We see deer, light-flooded canyons, a majestic yacht, endless mountain roads and a nude bather, Provost’s partner Hannelore Knuts. At times there are also digitally added glimpses of white celestial bodies, floating close but soothing in the bright sky. In Provost’s own words, together they form “a kind of living postcard in which the viewer can revisit the abandoned planet as a tourist”. He feels that we are nearing the end of capitalism, a collapse which you can already notice by the megalomaniac and sad desire to colonise other planets.

Nicolas Provost, Exodus, Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp, Belgium

The hope that we – or, according to Provost, our elite – project onto outer space is one element of the second part of ‘Exodus’. Another is the horror that is inherent in the vast and harsh cosmos: being enrobed by the mirrored video projection is equally blazing and mind-blowing as it is frightening, a dizzying feeling that is fuelled by the ever-intensifying soundscape. At the climax of that sci-fi and seventies-like sound loop and after seeing space ships, scorching rocket launches, solar flares and dazzling and colourful intergalactic wanderings being doubled into geometric patterns, we witness an astronaut, tumbling into eternity without a lifeline.

It is a sobering sight from a man who, in a sense, also let go of someone in the cosmos, as he became a father last year. In Dream Machine, a recently released overview of “the first chapter” of his career, he included a letter to Angelo Apollo, his son. “I know that you are as fragile as I am in a life that is precarious,” he writes, “[…] there is no fixed place in the universe, everything is in motion. You, spinning on a bike, on a spinning earth around a spinning sun, in a spinning galaxy, will never stop moving […]” How are we to think and act then in this constant and fragile motion? There are clues in his wise and beautiful letter, as there are in his answers to the following questions.

Nicolas Provost, Exodus, Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp, Belgium

Artdependence Magazine: When I saw the first part of Exodus, the rock formations and desert made me think of those in Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970) and Herzog’s Fata Morgana (1971), two films in which those elements are presented as a symbol of a man-made apocalypse. They – definitely the desert – attained that symbolic value as a result of media covered atomic tests and an increasing climate awareness since the ’50. Despite that connotation, your work breathes the vision of a more serene and less hectic world. Can you tell us more about the friction between the image of doom that deserts often evoke and the dreamscape that you want to present?

Nicolas Provost: I wanted to create a world of the near future, one after our western civilization has gone too far. But instead of making apocalyptic images, I chose images that feel peaceful and idyllic. As if we’ve learned our lesson in the silence after the storm. For a while, anyway. I travelled with a slow-motion camera through four states in the west to create a living slideshow in CinemaScope format. I wasn’t thinking about the references that you bring up, but they are obviously touching the same themes.

Nicolas Provost, Exodus, Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp, Belgium

AD: Is that dreamscape the reason why there is suddenly a cowboy, as rocks and deserts were understood as signs of unbridled possibilities by their connotation within the western genre prior to the ’50?

NP: I wanted to create cinematic scenes in the iconic landscapes of the American West because they are part of our collective memory. The desert landscapes evoke a lot of tension. If you’re in one, you feel like you cannot go anywhere if danger is coming at you from afar. I’m incredibly fond of that tension. Because of the scorching heat and the minimalist compositions that they evoke, it looks like you are walking between dream and nightmare, my favourite place, both in my waking life and in my sleep.

AD: In the second part of Exodus, there is the opposite movement. According to your comments in other interviews, you focus on the alarming colonization of space, while the viewer and movie fans will rather think of recent films as The Martian (2015), Interstellar (2014) and Gravity (2013). Do you agree with me or how do you feel about this?

NP: On the one hand, I find it encouraging, on the other, alarming. I am convinced that man knows very well how he can live in harmony with his fellow man and with nature. Today we have all the knowledge, spiritually and technologically, to accomplish that quickly. And yet, it seems as if the whole world is kidnapped by a small group of extremists with psychopathic tendencies, be it religious or capitalistic. The only reason they dominate the world is that they own the media, which empowers them to manipulate and polarise the people. We urgently need a political system that is truly democratic and an education system that is not performance-oriented but focused on humanism and creativity. I am fascinated by astrophysics and cosmology in general, but I would urge to first solve our problems on Earth before we exterminate ourselves completely. Then again, if you look at the history of the world and its civilisations, it’s written in the stars that we will extinguish ourselves. Artificial intelligence and climate change will make that happen faster than we think. It is inevitable that living species disappear, but humans will do it to themselves.

Nicolas Provost, Exodus, Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp, Belgium

AD: What Jeroen Laureyns stated a couple of years ago, no longer stands then? ‘Nicolas Provost is not trying to settle any accounts with his movies. Not with another genre, not with society and not with the world.’

NP: I’m in the middle of my career and welcome how I am changing as a person and an artist. I think that’s healthy. For example, it is more difficult for me to find a balance between being aware of the widespread corruption in the world on the one hand, and maintaining a naivety to continue to see the beauty and to translate it to my fellow man on the other. Today, I certainly don’t consider myself a political artist, because I’m trying to create works that transcend themselves by their aesthetics and their concept. But I feel I have a stronger desire than before to expose the corruption and to bring people closer together. One that is more fit for my fiction work. I’m developing different ideas for a couple of new feature films but I want to take my time. After The Invader I went back to making art, and we’ll see when I find the time to focus and finish a script.

AD: You often use mirror techniques in your videos. In de Warande, the mirroring is for the first time not only in the projection, but also in the mirrored room around it. Did you have this idea for some time and are you pleased with how it was executed?

NP: I have long wanted to make a projection into a mirror space. When Annelies Nagels, the curator of de Warande, asked me to do an exhibition there, I didn’t hesitate because the spaces are perfect to make monumental video installations. And since I had used the mirror technique in the editing in many of my films, I wanted to see if I could use that same technique as a larger 3D experience. The interesting part of this mirror installation is that one experiences it in different stages. First, you see it from a distance and only when you start walking towards it, you realise it is a 3D object that you can step into.

AD: An important component of the work is the soundscape. Can you tell us more about the importance of sound in your work and the realization of the heady score that blares through the two rooms?

NP: Sound is half of my art. Even if I choose to make a film without sound is it present as silence. I try to make it deafening then. For the mirror room, the intention was to create an audio-visual experience that you can enter and lose yourself in. But one with an ambiguous feeling, where you both transcend and become aware of the horror that the universe harbours. To achieve this sense of transcendence, I again worked with Senjan Jansen. It is very rewarding to work with someone that knows your affinities and artistic vision very well. It’s been fifteen years since our collaboration started. For this piece, I have given very little instruction. I wanted a musical electro sound that starts from nothing and ends in a big climax, in one straight line. Something that drags you emotionally and then abruptly stops to make you tumble. I cannot imagine a better score.

AD: You call upon the unconscious cinematographic memory of the viewer, in particular on the codes, conventions and clichés which make up a universal film language. In what sense has that language changed the past decade?

NP: I think it’s difficult to say how film language has changed the past ten years. Because of the technology, cinematography has gotten more advanced, but that doesn’t mean it is artistic better then what cinematographers were doing prior to the digital revolution. It’s hard to put a finger on how acting changes over a decade, but one hopes that women are getting better roles to play, roles for a real, full human being and not just the two-dimensional love interest in function of the male role. Also, I think that in the golden years of cinema, actors in general were more interesting personalities and less political correct. That’s something I really miss today. Where are the new Dennis Hoppers, Jack Nicholsons, Al Pacinos, Paul Newmans and De Niros?

Cinema is competing with TV now. There’s a lot going on in TV land lately and I’m curious to see where it’s going. It’s a great place to experiment with new story and character development because there is more time. But I think that will distinguish cinema even more as a greater form of art. It will have to be even more courageous and come up with a way to get the audience back. I do think that over time, people will get tired of the Hollywood superhero idea. I mean, how far can you go with a hero that can do everything? It’s boring and it’s already saturated. To quote Paul Schrader, cinema is in a revolution at the moment, but a revolution of form. And it’s very difficult for content to keep its head above water during a revolution of form. We don’t know any more what cinema is or how to watch it.

AD: What is your view on contemporary cinema?

NP: I think that a lot of great contemporary cinema is not being distributed. Smaller distributors have a hard time competing with the commercial market. In the US, only 20% of cinema is made by the studios, yet they dominate 80% of the market. That means independent cinema competes on a very small platform where they become each other’s competitors.

AD: Do you fear that the younger generations have less film knowledge and that the art lovers among them will therefore look differently of even less thorough at your work?

NP: I never think of how younger generations will look at my work. I just try to make something that I think would move me if I were the audience and I can only hope that my work stays timeless. Sometimes I think that to achieve that, I should be even more radical. But I’ve met intelligent and creative young people that had never seen a Kubrick film and knew vaguely about Hitchcock. That was a big reality check for me. Knowledge of film history can be lost quickly.

AD: Which films and directors do you appreciate and why?

NP: Sometimes there’s a film that changes some parameters in cinema. I think Under the Skin (2013) did a good job at that in its first three quarters. The film took me by surprise because I had never seen something like that. Jonathan Glazer, the director, created a new world, full of suspense, with very simple means. The older I get, the more I think that this is what it should be all about: surprise and suspense.

AD: A major change coming at us is virtual reality. Are you aching to work with that or are you hesitant?

NP: I’m very curious to see what the possibilities will be. I think there’s a future in being part of the story. I myself would love to be a character in a story, like smoking a joint and stepping into the life of an antihero for a couple of hours.

AD: Don’t you think these and/or other technological achievements eliminate the distance between the viewer and the work? Or else: is distance necessary to consider a work of art or is a physical and mental immersion equivalent (or even better)?

NP: Art is something that holds a mirror to life. I think the more simple the means to do that, the greater the art. I don’t know how soon cinema will be caught up by new forms of storytelling, but I hope that telling a story from left to right on a 2D screen, which is what we do today, will become a classic old-fashioned medium, like painting.

AD: Because you rely on those codes, you are striving for a degree of accessibility and readability in your work, but where is the boundary with the exciting and challenging mystery, which is equally present?

NP: Film is a language of ideas and emotion. When I start a project, I see something visual that is still vague but that I feel has clearly potential to grow into an interesting moving story, whether it be abstract or narrative. Along the way, I try to sculpt my way around a storyline that has a constant tension curve towards a climax. I try to have a very personal conversation with my audience. I take them very seriously, because I know that unconsciously, people can read abstraction, and that’s where I try to meet them. I think that’s emotional.

AD: In an earlier interview you stated: ‘It’s impossible to find rest – peace.’ Is this still the case? The first part of Exodus is very zen.

NP: I’m not working towards a body of work that has a consistent and recognisable style. My work is eclectic. The only thing that I try to be consistent with is the poetic conversation that I have with my audience. Today I mostly work in film, video and photography, but that might change. Who knows. All I hope is that I can continue to be a fulltime artist until I die.

ArtDependence Magazine is an international magazine covering all spheres of contemporary art, as well as modern and classical art.

ArtDependence features the latest art news, highlighting interviews with today’s most influential artists, galleries, curators, collectors, fair directors and individuals at the axis of the arts.

The magazine also covers series of articles and reviews on critical art events, new publications and other foremost happenings in the art world.

If you would like to submit events or editorial content to ArtDependence Magazine, please feel free to reach the magazine via the contact page.