To celebrate the anniversary of his death, ArtDependence will write a series of stories aimed at understanding the worldview of the man considered to be history’s greatest artist and one of its brightest minds. Only in the process of grasping his vision of the universe we begin to understand how he managed to almost recreate the mystery of life in his paintings; conceive of objects way beyond the technical capacities of his time like knight robots, parachutes, and self-propelling carts; and compile an encyclopedia of knowledge that reflects on the various dimensions of existence.

Image: Mona Lisa (1503), Leonardo Da Vinci

When Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci died in 1519 one of his lifelong servants, Francesco Melzi, said: “Everyone was grieved by the loss of such a man whose like Nature no longer has it in her power to produce.”

To celebrate the anniversary of his death, ArtDependence will write a series of stories aimed at understanding the worldview of the man considered to be history’s greatest artist and one of its brightest minds. Only in the process of grasping his vision of the universe we begin to understand how he managed to almost recreate the mystery of life in his paintings; conceive of objects way beyond the technical capacities of his time like knight robots, parachutes, and self-propelling carts; and compile an encyclopedia of knowledge that reflects on the various dimensions of existence.

Mona Lisa (1503), Leonardo Da Vinci

Mona Lisa (1503), Leonardo Da Vinci

In the Eyes of a Genius

The apparent unlimited capacity of Leonardo da Vinci’s mind has fascinated and baffled the world for 500 years. A big piece of his brilliance’s puzzle lies in his vision of nature.

To da Vinci the purpose of human understanding was to study nature’s designs. With titanic diligence he dedicated his life to doing just that. He wrote over 300 pages just on the natural phenomena painters should take into account; when learning about water he conducted around 730 experiments, and his study for The Last Supper (1495-1498) –one of his most famous artworks- began by searching how the sensory input and muscular output of the medulla and the nerves affect men and women’s contours. This allowed him to depict betrayal in Judas’ face and consternation in the other Apostles.

The Last Supper (1495-1498), Leonardo Da Vicni

The Last Supper (1495-1498), Leonardo Da Vicni

His aim was adding “excellence to excellence and perfection to perfection,” writes renowned Renaissance art historian Giorgio Vasari in The lives of the artists. His quest for knowledge and meaning was so ambitious his hands, though extremely skillful, sometimes failed to keep up.

Going beyond a subject’s direct causes wasn’t a whim. To da Vinci all phenomena were interlinked. He could not think of something without thinking of something else. He believed in a unified theory capable of explaining how everything worked. The theory of everything made the attempt at indepth encyclopedic knowledge possible and crucial in order to grasp the universe’s soul.

His search for knowledge depended on his sight’s capacity. “If he could not see it he could not do it,” writes professor Martin Kemp, a renown da Vinci scholar, in his book Leonardo (2004). “He was a supreme visualizer, a master manipulator of mental ‘sculpture,’ and almost everything he wrote was ultimately based on acts of observation and cerebral picturing.”

Within his worldview his genius of sight was a gift into the mysteries of the universe. Following ancient and medieval philosophy da Vinci believed necessity drives Nature. No phenomenon is a surplus, forces expand in the most direct way possible, and the simplest design will be preferred. Under the rule of necessity function determines form, which made him confident he could figure out a things form if he knew its purpose.

Hand, Leonardo Da Vinci

Hand, Leonardo Da Vinci

Da Vinci saw the geometric proportions composing the world’s structural design. He recognized how series of numbers tend to repeat themselves in various natural phenomena. The Fibonacci series, for example, -in which every number after the first two is the sum of the two proceeding it-, appears in the pattern of the branching of trees, the flowering of an artichoke, a pinecone’s bracts, and the arrangement of leaves on a stem, among others.

Since the world’s principals of organization were shared to the deepest level, by knowing the inner workings of one phenomenon one could begin to figure out those of another. In this vision the human body becomes a microcosm mirroring the whole.

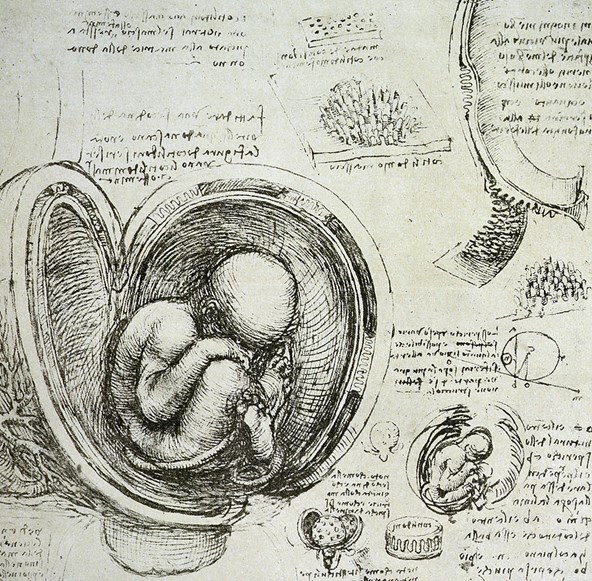

Fetus, Leonardo Da Vinci

Fetus, Leonardo Da Vinci

Da Vinci’s visual genius allowed him “to go beyond the generality of the analogy and to transform representation into a powerful analytical tool,” writes Kemp. Drawing was an act of understanding. Words could only go so far so he preferred to sketch a hand to discover the structure of the bones and how the muscles and tendons move the fingers. Through the lifelike image of a fetus in the womb he could explain how the head’s weight made the fetus rotate for birth, and his depiction of the heart’s pulmonic valve helped him understand blood’s path through the heart.

The mix of theory and practice that drove Newton and Galileo’s scientific revolution was already present in Leonardo. To him pure philosophy began and ended in the mind. Knowledge should be based on experiment. But his worldview allowed him to accept thought experiments as evidence, and to derive proofs from observing nature. Because he was a visual genius he excelled at both.

ArtDependence Magazine is an international magazine covering all spheres of contemporary art, as well as modern and classical art.

ArtDependence features the latest art news, highlighting interviews with today’s most influential artists, galleries, curators, collectors, fair directors and individuals at the axis of the arts.

The magazine also covers series of articles and reviews on critical art events, new publications and other foremost happenings in the art world.

If you would like to submit events or editorial content to ArtDependence Magazine, please feel free to reach the magazine via the contact page.