It is not a book you can read because it was never meant to be read. The publisher describes it as a playscript, but it seems highly unlikely that anyone could use it without supplementary knowledge to produce the piece it purports to script. Costume En Face was meant to be used by its writer, and perhaps by others doing the same kind of work, to take the work deeper. Period. It is an archival object rather than a traditional piece of writing.

3 Signals to the Mermaid: An Inadequate Reading of Costume En Face by Tatsumi Hijikata and/or Moe Yamamoto (Sawako Nakayasu trans.) [Ugly Duckling Presse 2015]

It is rare that a tiny obscure book from a tiny obscure press about a tiny obscure movement within the most obscure regions of the international art world gets reviewed by the New York Times. Here, it is classified (however tentatively) as “a dance book.”

Its sole other reviewer, Boston Review, plops it squarely in the “Summer Poetry Reads” section (though has trouble keeping it there.)

Costume En Face: A Primer of Darkness for Young Boys and Girls, eludes being captured fully in either review, and will likely do the same here.

It is not a book you can read because it was never meant to be read. The publisher describes it as a playscript, but it seems highly unlikely that anyone could use it without supplementary knowledge to produce the piece it purports to script. Costume En Face was meant to be used by its writer, and perhaps by others doing the same kind of work, to take the work deeper. Period. It is an archival object rather than a traditional piece of writing.

But for those with more general interest in the documentation of performance art, this strange printed object comprised of surreal phrases and chicken-scratched imagery might be something more than a playscript, “a dance book”, poetry, or a bit of chicness to keep on your coffee table for a little while.

It may well hold answers to some of the most complex contemporary questions about the capturing of gesture and experience. Questions such as how do you keep photographic or video documentation from standing in as a substitute for live engagement with an artwork? Or how do audiences, artists and documentarians (“the media” or academics) collectively generate a work's meaning and value? These questions apply across the arts, but are brought into sharper relief by the rise of attention focused on performance in the contemporary art world in recent years. In this context, everything that is and is not ephemeral about connecting with art becomes much more clearly articulated.

Dancer: Moe Yamamoto. Photographer Unknown. Image courtesy of the Tatsumi Hijikata Archive, Keio University Art Center, Japan

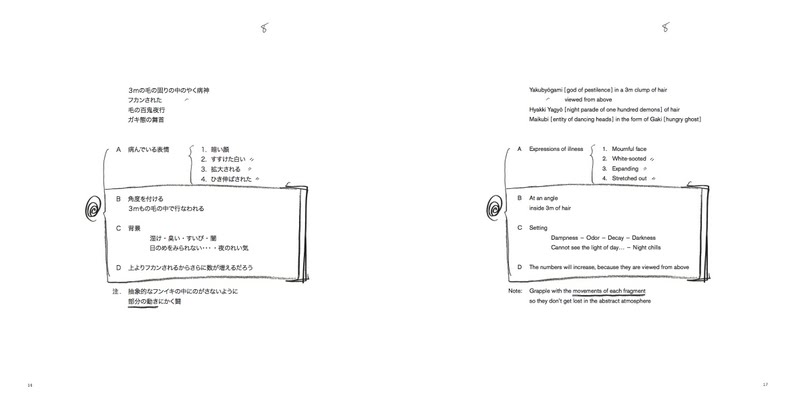

Approaching the book itself as if it were a performance, the title pages, copyright information and table of contents are unassuming and straightforward. But the first page of content—a list of the book's illustrations—point immediately to a new kind of reading experience. The book has only 5 illustrations (actually, it has many illustrations—this list refers only to the photographs it contains) and these are their titles:

A list like this stops you from just flipping the page and beginning the introduction to a book. Instead, you are compelled to flip immediately to each image and investigate. In this case, the reward for doing so is that you are (in all but one of the cases,) even more deeply mystified by the image titles.

Even authorship is a bit slippery here. But then authorship is sometimes slippery with performance art. Does the audience make something a performance? The performer? Or the artist who conceived the work?

In this case, Tatsumi Hijikata, the choreographer of the “dance” being articulated in the text, and the founding father of the Butoh style of dance, is credited as the author of the book. But then, in a much smaller font below, the book is described as a notebook written by the original dancer of the piece, Moe Yamamoto.

The book's introduction, by Takakashi Morishita, Director of the Hijikata Archive at Keio University, addresses this problem without resolving it at all.

“The words came from Hijikata, and yet the actual notation of these words are subject to a certain kind of arbitrariness, based on Moe Yamamoto's understanding and judgement. For each word in the notebook there is a 'movement' invented by Hijikata. Words are a metaphor for movement....Tatsumi Hijikata created a work of dance called Costume en Face. It is only because of this method of creating dance that Moe Yamamoto was able to play the leading role, and that Hijikata was able to complete this work featuring Yamamoto.”

Or rather, it doesn't resolve the work's authorship, but it explains its value: it is a window into a the previously almost completely obscured working methods of Hijikata as he developed the nascent art form of Butoh dance. This all sounds reasonable until you try to actually interpret the text. Then the window feels like a peephole. A very grimy peephole.

For example:

“Peacock Ride

Walking horse” (page 43)

or:

“Monotonous hand fluttering Midget

Brain

Goya's Idiot

Swallow a fist” (page 57)

or: “Blindingly bright girl Black on the backside Intense light” (page 66)

The gestures that these phrases refer to continue to be, as Morishita puts it, “shrouded in mystery” for anyone who was not in or did not see the dance. Also, how does a text like this one synch up with a video like this one?

The video documents a different dance and performance than the book does, but it doesn't undermine the point: from even this short clip, there's little question that the text on the pages quoted above could be not presumed by seeing the dance which they represent.

And yet they do represent that dance.

How? For one thing, via the very act of keeping the “mystery” of the creator's ideas shrouded. For another thing, by encoding so much interpersonally transmitted information into minimal bits of language that it becomes crystal clear on even a first glance that a large percentage of what you're seeking there won't be found. And finally by pure poetic force.

These words will not sit on the page. They will not crawl into your mind and release clear visions of the piece's settings or actions. They will not place you in the room with Moe Yamamoto and Tatsumi Hijikata, like a fly on the wall watching as each movement gets refined to “perfection” in rehearsal.

Instead, the words here dance around on the page themselves; the imagery slams from one end of the universe of possibilities to the other without pause; and the dancer and choreographer—despite being the transmitters of the text—are barely there. They are there in little scratchily-drawn sketches of horses' necks and the spacing of the words on the page, but the words themselves seem to emerge directly from the artists' subconscious. Or from their bodies. They read like projectiles emitted from them in dream-states while they are shuddering hard.

This linguistic liveliness brings us back towards the actual performance by indexing it rather than covering it. We don't wind up with the sense that we have been there and seen Costume En Face, only that we would need to in order to make complete sense of the text. This is an invaluable model for and service to live performers of all mediums and genres. In an era where well-lit, high resolution documentation is the key to an artwork being recognized as an artwork, the insistence here on keeping the live in live art while simultaneously archiving its existence is a much needed guidepost on a pathway to preservation of the experiential alongside the historical.

Costume En Face, leaves you wanting more information and it should, because Butoh itself leaves tremendous space in its staging. Minimalist sets and small, sharp gestures trigger abstract, cascading internal experiences that less poetic movements would not. This difficult read opens up on you in much the same way.

And then it closes with additional commentary from Takakashi Morishita. Morishita explains the significance of this particular notebook of Butoh-fū or notation, separating out the book's dense layers of information, mapping each type of writing or sketching to a layer of interaction between Hijikata and Yamamoto. The density is relieved slightly at the end of the book as a result, but the shroud between the live and the archived still does not lift.

“These notes were mostly in 'code.' Each word can be understood to be the name of a 'movement,' but a third party could not know the actual movements created by Hijikata and then choreographed for Yamamoto.”

Copyright Takashi Morishita, 2010.

Copyright Moe Yamamoto, 1976. English translation copyright Sawako Nakayasu, 2015.

Morishita does try to break the code—dividing the work into number of occurrences of named movements, presumably for comparison with films of the performance (which exist.) And has gone so far as to capture Yamamoto on video recreating many of the book's movements on for posterity.

But he ultimately admits to the book's limitations in transmitting the work beyond its original performance, calling it “only one piece of the puzzle.”

If you prefer unfinished puzzles to finished ones, and/or are looking for new ways to think about the representation of live performance or deeply contextualized artwork, you should find Costume En Face very satisfying.

For more information about Ugly Duckling Presse click here.